In 1847, Zeb and Arabella Rudolph decided that their daughter Lucretia needed more of an academic challenge than the local Garrettsville, Ohio, schools could offer. The fifteen-year old was sent twenty miles away to board at the Geauga Seminary, where she would have the benefit of a classical curriculum. The Geauga Seminary was coeducational, and one of Lucretia’s fellow pupils there was an awkward and earnest sixteen-year old boy named James Garfield.

In 1847, Zeb and Arabella Rudolph decided that their daughter Lucretia needed more of an academic challenge than the local Garrettsville, Ohio, schools could offer. The fifteen-year old was sent twenty miles away to board at the Geauga Seminary, where she would have the benefit of a classical curriculum. The Geauga Seminary was coeducational, and one of Lucretia’s fellow pupils there was an awkward and earnest sixteen-year old boy named James Garfield.

“A prodigy,” Lucretia called him.

In 1850, Lucretia left the Geauga Seminary and enrolled in the new Hiram Eclectic Institute in Hiram, Ohio. The following year, Garfield also enrolled at Hiram, and Lucretia experienced the unexpected thrill of meeting “a pair of eyes…as once I looked up from a hard sentence somewhere in the fore part of the Greek grammar.” It wasn’t exactly love at first conjugation—both she and James were recovering from painful break-ups—but in 1853 James surprised Lucretia with a letter written during an excursion to Niagara Falls, and soon the two were engaged in a full-fledged correspondence.

At first, they addressed each other as Brother and Sister. They wrote about the books they were reading, and about their shared enthusiasm for teaching. James was teaching Latin and Greek at Hiram, and Lucretia was teaching at a public school in Chagrin Falls, and attempting to keep pace with James’s Latin class in reading Virgil.

“I would like to know how many hundred lines the Virgil class are ahead of me,” she wrote to James in November 1853.

“Today, the Virgil class finished the third book and are going about 50 lines per day,” Jame wrote back on December 8. “Are you ahead? I presume so. Won’t you come in to both Greek and Latin in the spring? We miss you very much in these two classes. What are your views with regard to studying the classics? Have you reconciled yourself to devoting a few more years to them? I would like to hear your reasonings on the subject.”

Replying six days later, Lucretia confessed that she had laid aside Virgil for the winter. As to the study of classics in general, she wrote: “Candidly, I will confess that thus far I have prosecuted the study of them without any argument in their favor which appeared to me conclusive.” She admitted that the study of Greek and Latin provided “rigid mental discipline,” but she wondered if there might be other means of acquiring that discipline.

“I wish you would convince me of their superior merit if they really possess it,” she wrote; “for I do not like to give them up—neither do I like to continue in them feeling that precious moments are being wasted…”

This discussion continued in several letters over the following months. Meanwhile, James quietly dropped the pretense of calling her Sister, and soon Lucretia was sending James her “warmest love.” In March 1854, the subject of marriage was raised.

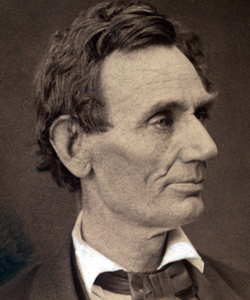

James A. Garfield—veteran of Shiloh and Chickamauga, Union general, and twentieth President of the United States—courted his wife with a debate over the value of a classical education.

The correspondence of James and Lucretia Garfield can be found in John Shaw, ed. Crete and James: Personal Letters of Lucretia and James Garfield (Michigan State University Press 1994). For a biography of Lucretia Garfield, see John Shaw, Lucretia (Nova History Publications, 2001). On James Garfield’s study of the classics, see Susan Ford Wiltshire’s essay, “The Classicist President” (.pdf).