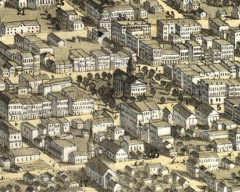

“The Cannon Salvo that thundered over Springfield, Illinois, to greet the sunrise on November 6, 1860, signaled not the start of a battle, but the end of one…Election Day was finally dawning.” – Historian Harold Holzer

“The Cannon Salvo that thundered over Springfield, Illinois, to greet the sunrise on November 6, 1860, signaled not the start of a battle, but the end of one…Election Day was finally dawning.” – Historian Harold Holzer

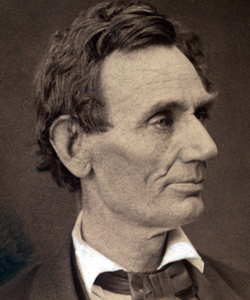

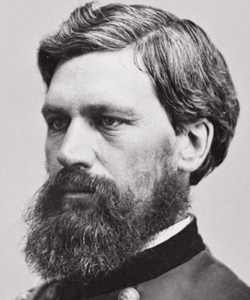

Abraham Lincoln, however, was not one to rush and vote right after the polling places opened in the morning. He apparently waited until 3:30pm when, as the New York Tribune explained, “the multitude…[had] diminished sufficiently to allow tolerably free passage.” The Tribune’s correspondent described what happened once the crowd realized that Lincoln had arrived:

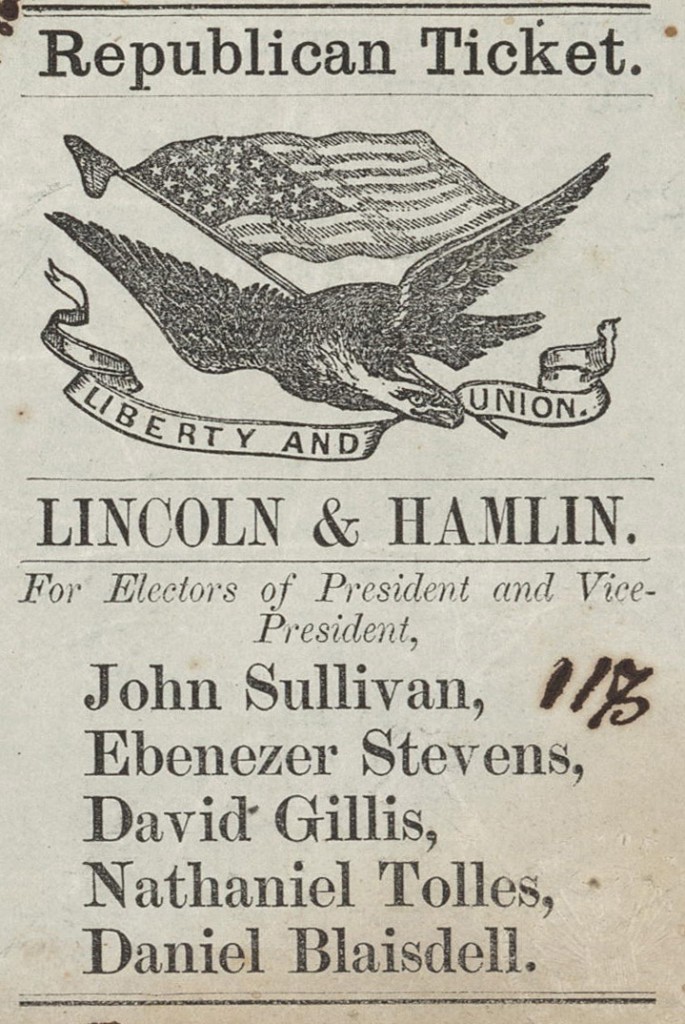

“at that moment he was suddenly saluted with the wildest outbursts of enthusiasm every yielded by a popular assemblage. All party feelings seemed to be forgotten and even the distributors of opposition tickets joined in the overwhelming demonstrations of greeting…there was only one sentiment expressed – that of the heartiest and most undivided delight at his appearance. Mr. Lincoln advanced as rapidly as possible to the voting table and handed in his ticket, upon which, it is hardly necessary to say, all the names were sound republicans. The only alteration he made was the cutting off of his own name from the top where it had been printed.”

As Holzer explains, “Lincoln modestly cut his own name..from his ticket” and “vot[ed] only for his party’s candidates for state and local office.” Later that evening Lincoln went to the local telegraph office, where he waited for reports on election returns from across the country. “All safe in this state,” as Thurlow Weed explained from Albany, New York. Simon Cameron sent word from Philadelphia, Pennsylvanian, while a report from Alton, Illinois, noted that “[Republicans] have checkmated [Democrats’] scheme of fraud.” “Those who saw [Lincoln] at the time,” as the New York Times observed, “say it would have been impossible for a bystander to tell that that tall, lean, wiry, good-natured, easy-going gentleman…was the choice of the people to fill the most important office in the nation.”