“He said, in substance, Ninety years ago our fathers formed a Government consecrated to freedom and dedicated to the principle that all men are created equal.” Centralia (IL) Sentinel November 26, 1863, from coverage of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

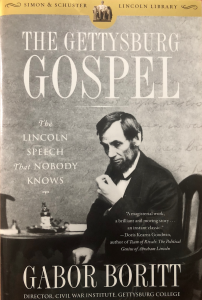

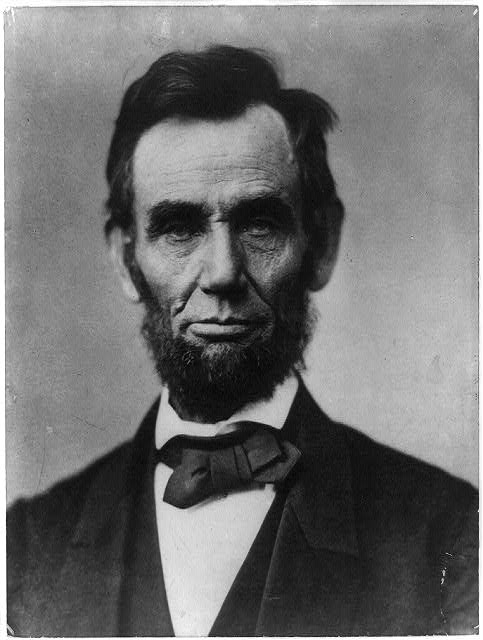

Ninety years ago? Imagine being the Civil War-era reporter who did not believe that the phrase “Four score and seven years ago” was memorable enough to record in its exact language. Yet historian Gabor Boritt includes this passage from the Sentinel’s slightly botched coverage of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in his book, The Gettysburg Gospel (2006). Boritt uses the example as a way to highlight the surprisingly complicated story about how Lincoln’s brief speech at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery dedication was received in late 1863 and then how the memory of it changed 0ver the years that followed. Boritt’s book introduces readers to a host of primary sources, including numerous historical newspaper accounts, that show a wide range of reactions to Lincoln’s now-famous and universally-celebrated words. This post attempts to organize some of these sources for teachers and students to view themselves. In addition, I have started to collect various post-war recollected accounts of the dedication ceremony, including some that Boritt does not feature, as a way to provide first-hand accounts of that memorable day on November 19, 1863.

Ninety years ago? Imagine being the Civil War-era reporter who did not believe that the phrase “Four score and seven years ago” was memorable enough to record in its exact language. Yet historian Gabor Boritt includes this passage from the Sentinel’s slightly botched coverage of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in his book, The Gettysburg Gospel (2006). Boritt uses the example as a way to highlight the surprisingly complicated story about how Lincoln’s brief speech at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery dedication was received in late 1863 and then how the memory of it changed 0ver the years that followed. Boritt’s book introduces readers to a host of primary sources, including numerous historical newspaper accounts, that show a wide range of reactions to Lincoln’s now-famous and universally-celebrated words. This post attempts to organize some of these sources for teachers and students to view themselves. In addition, I have started to collect various post-war recollected accounts of the dedication ceremony, including some that Boritt does not feature, as a way to provide first-hand accounts of that memorable day on November 19, 1863.

Local Reactions

“How the president’s words were reported would impact how they were received. People often read papers out loud, and what they heard, if they read his remarks, varied widely.” (Boritt, 142)

- (Gettysburg, PA) The Adams Sentinel, “Speech of the President,” November 24, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- (Lancaster, PA) Daily Inquirer, “The Gettysburg Celebration,” November 20, 1863 [IMAGE][FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Genealogy Bank)

- (Harrisburg, PA) The Patriot News, “President Lincoln’s Last Speech,” December 3, 1863 [IMAGE] (Courtesy of Genealogy Bank)

- This one is especially teachable because the paper retracted their criticism many years later.

- Union County (PA) Star and Lewisburg Chronicle, “Dedication at Gettysburg,” November 27, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Chronicling America)

Republican Reactions

“The Republican papers printed overwhelmingly favorable editorial comments.” (Boritt, 131)

- Chicago Tribune, “The Consecration of the Battle Cemetery,” November 21, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- (Montpellier, VT) The Daily Green Mountain Freeman, “Consecration of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg,” November 21, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- New York Times, “The Heroes of July,” November 20, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL ARTICLE] (Courtesy of New York Times Online Archives)

- The editor of the Times, Henry Raymond, served as chairman of Lincoln’s reelection campaign in 1864.

- (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, “Inauguration of the Gettysburg Cemetery,” November 23, 1863 [IMAGE][FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Genealogy Bank)

- This article by Lincoln’s hometown newspaper ends with noting the tremendous applause he received following his remarks at the cemetery.

- (Washington, DC) Weekly National Intelligencer, “The Ceremonies at Gettysburg,” November 26, 1863 [IMAGE][FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

Democratic Reactions

“Most of the Democratic papers tried to hide, or entirely ignore, the president’s speech, which they regarded as the start of his presidential campaign.” (Boritt, 140-141)

- Baltimore Sun, “The National Cemetery,” November 20, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- The Sun mostly avoided criticism of the president’s remarks.

- Clearfield (PA) Republican, “A Voice From the Dead,” December 2, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- The column attacked both Edward Everett and Lincoln for allegedly making the dedication about themselves.

- (Ebensburg, PA) Democrat and Sentinel, “The Gettysburg Cemetery,” December 2, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- This account aggressively misquoted the president to make it appear as if he was not appreciating the fallen.

- (Indianapolis) The Indiana State Sentinel, “The President at Gettysburg,” November 30, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- Lincoln is yet again attacked for trying to be political at the dedication.

- New York Herald, “Consecration of the National Sepulcher at Gettysburg,” November 20, 1863 [IMAGE][FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- The Herald focuses on the soldiers who fought rather than any of the speeches at the dedication.

- Philadelphia Inquirer, “Gettysburg Celebration,” November 20, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL ARTICLE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

British Coverage

- (Colchester, UK) The Essex County Standard, “Later Intelligence,” December 4, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- (London, UK) The Morning Post, “The Civil War in America,” December 12, 1863 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

Recollections

- Noah Brooks, “Personal Reminisces of Lincoln,” Scribner’s Monthly, Vol. 15 (Feb. 1878), p. 565 [IMAGE] (Courtesy of HathiTrust, digitized by Cornell University)

- Brooks was a leading journalist who described his interactions with Lincoln leading up to the speech, and how he remembered the president writing the speech.

- [John Hay], The Holton Recorder (KS), “Lincoln the Author of His Gettysburg Address,” January 3, 1884 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- Hay, who was Lincoln’s personal aid, admitted to signing the President’s name often but assured he had nothing to do with the Gettysburg Address.

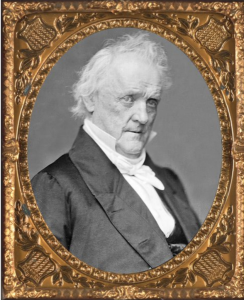

- [Samuel Schmucker], Adams County News (PA), “Death of Judge S. D. Schmucker,” March 11, 1911 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- Schmucker was a local jurist who viewed the speech as a young man.

- [James Speed], The Chicago Tribune, “A Pretty Little Fiction,” April 20, 1887 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE] (Courtesy of Newspapers.com)

- Speed, who served as Lincoln’s second attorney general, disputed the impression that Lincoln wrote the speech on the train to Gettysburg.

- [David Wills], The Carlisle Sentinel (PA), October 7, 1885 [IMAGE] [FULL PAGE]

- Wills was the local attorney who hosted the president at Gettysburg and recalled that Lincoln wrote at least the final version the speech in his house.

Further Reading

Boritt, Gabor. The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech that Nobody Knows. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006.

Pinsker, Matthew. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Addresses. House Divided Project exhibit at Google Arts & Culture, 2013.

The reaction to President Obama’s

The reaction to President Obama’s

“The war was a good time for the study of the conflict between Athens and Sparta,” Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) wrote in 1897. “It was a great time for reading and re-reading classical literature in general, for the South was blockaded against new books as effectively, almost, as Megara was blockaded against garlic and salt… The Southerner, always conservative in his tastes and no great admirer of American literature, which had become largely alien to him, went back to his English classics, his ancient classics. Old gentlemen past the military age furbished up their Latin and Greek. Some of them had never let their Latin and Greek grow rusty.”

“The war was a good time for the study of the conflict between Athens and Sparta,” Basil Lanneau Gildersleeve (1831-1924) wrote in 1897. “It was a great time for reading and re-reading classical literature in general, for the South was blockaded against new books as effectively, almost, as Megara was blockaded against garlic and salt… The Southerner, always conservative in his tastes and no great admirer of American literature, which had become largely alien to him, went back to his English classics, his ancient classics. Old gentlemen past the military age furbished up their Latin and Greek. Some of them had never let their Latin and Greek grow rusty.”