Ranking

#18 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

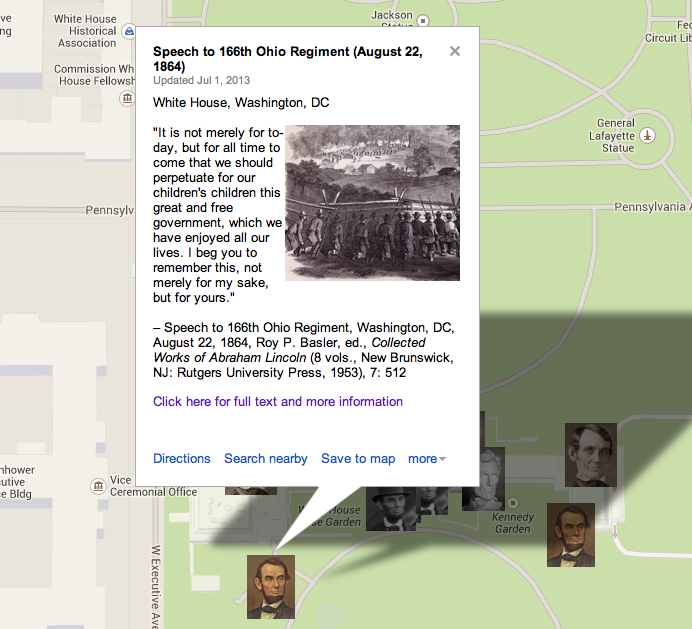

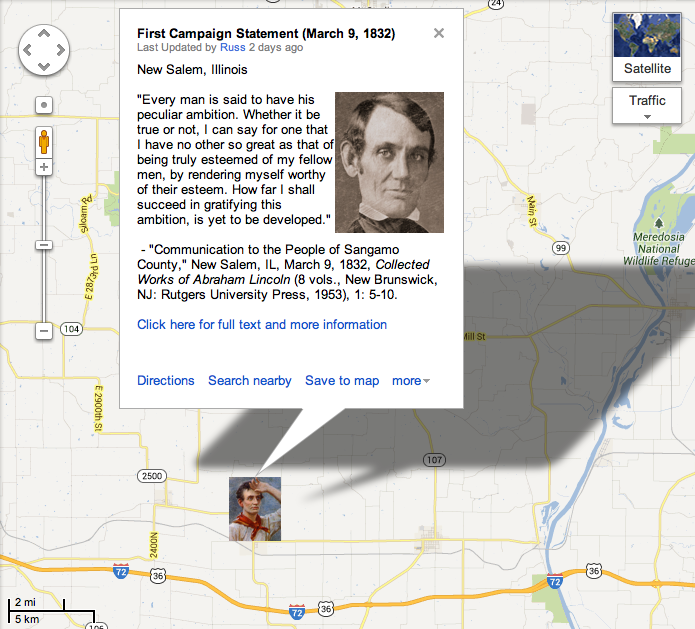

Context. Abraham Lincoln was twenty-three-years-old and working as a clerk in a store in the small village of New Salem, Illinois (situated about 20 miles north of Springfield along the Sangamo or Sangamon River) when he announced himself in 1832 as a candidate for the Illinois state house of representatives. Lincoln competed against twelve other candidates for four at-large seats. He finished eighth in the August election, falling short of victory by only about 150 votes. His well-crafted campaign statement from March, which detailed his policy positions on issues such as river improvements, may have contributed to what was a reasonably strong showing for someone who had only been living in the district for less than a year. (By Matthew Pinsker)

“To the People of Sangamo County….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, March 9, 1832

Image Gallery

-

-

Sangamon County, IL

-

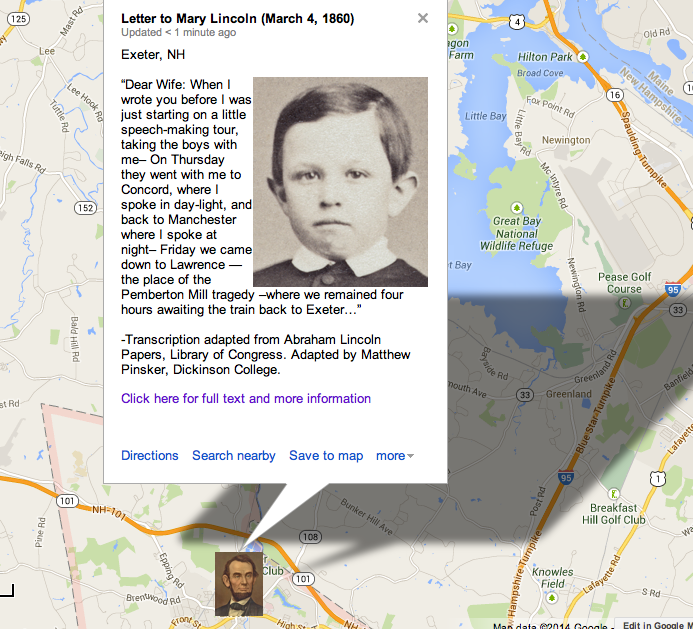

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

Other Primary Sources

“Presidents Message – No. III (3d.) Internal Improvements,” Southern Times and State Gazette (Columbia, SC), January 3, 1831

How Historians Interpret

“At his friends’ urging, Lincoln in March 1832 announced himself a candidate for the state legislature. The move was another demonstration of the young man’s supreme self-confidence, his belief that he was at least the equal, if not the superior, of any man he ever met. To be sure, the post he was seeking was not an elevated one … Nevertheless, Lincoln’s decision to announce himself a candidate for the state legislature in March 1832 was a revealing one. Less than a year earlier he had been, in his own words, a ‘friendless, uneducated, penniless boy, working on a flatboat – at ten dollars per month.’ … Other candidates had influential politicians present their names to the electorate, but Lincoln, lacking such support, appealed directly to the public in an announcement published in Springfield’s Sangamo Journal. In drafting and revising it, he probably had some assistance form John McNeil, the storekeeper, and possibly from schoolmaster Mentor Graham, and they may have been responsible for its somewhat orotund quality … In a concluding paragraph Lincoln spoke for himself, rather than for his community, and here he employed his distinctive style, avoiding highfalutin language in favor of simplicity and directness.”

—David H. Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 42-43

“In his campaign announcement of 1832, Lincoln had told the people of Sangamon County that his chief desire was to be ‘esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem.’ In a brief two years, Lincoln’s abilities and experiences began to coalesce into his gifts of leadership. His intellectual curiosity had pushed beyond the romantic and religious classics he read in his Indiana years to Enlightenment authors who offered critiques of religion. Now feeling at home after living three years in New Salem, he was beginning to find his own voice, not just around the fireside at the country store, but in campaigning in the countryside beyond the little town, where he was known for his clearheaded thinking, whimsical storytelling, and self-deprecating humor. Lincoln’s ambitions for public service were about to be tested and shaped in the larger arena of the Illinois Ninth General Assembly.”

— Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Biography (New York: Random House Inc., 2009), 60

“In his 1832 campaign announcement, Lincoln above all championed government support for internal improvements which would enable subsistence farmers to participate in the market economy and thus escape rural isolation and poverty … Lincoln’s ambition, like that of many politicians, was rooted in an intense craving for deference and approval. But unlike many power-seekers, Lincoln was expansive and generous in his ambition. He desired more than ego-gratifying power and prestige; he wanted everyone to have a chance to escape the soul-crushing poverty and backwardness that he had experienced as a quasi-slave on the frontier.”

— Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript By Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 1, Chapter 3 (PDF), pp. 248-251

Further Reading

For educators:

For everyone:

Searchable Text

To the People of Sangamo County March 9, 1832

FELLOW-CITIZENS: Having become a candidate for the honorable office of one of your representatives in the next General Assembly of this state, in accordance with an established custom, and the principles of true republicanism, it becomes my duty to make known to you—the people whom I propose to represent—my sentiments with regard to local affairs.

Time and experience have verified to a demonstration, the public utility of internal improvements. That the poorest and most thinly populated countries would be greatly benefitted by the opening of good roads, and in the clearing of navigable streams within their limits, is what no person will deny. But yet it is folly to undertake works of this or any other kind, without first knowing that we are able to finish them—as half finished work generally proves to be labor lost. There cannot justly be any objection to having rail roads and canals, any more than to other good things, provided they cost nothing. The only objection is to paying for them; and the objection to paying arises from the want of ability to pay.

…The probable cost of this contemplated rail road is estimated at $290,000;—the bare statement of which, in my opinion, is sufficient to justify the belief, that the improvement of Sangamo river is an object much better suited to our infant resources.

Respecting this view, I think I may say, without the fear of being contradicted, that its navigation may be rendered completely practicable, as high as the mouth of the South Fork, or probably higher, to vessels of from 25 to 30 tons burthen, for at least one half of all common years, and to vessels of much greater burthen a part of that time. From my peculiar circumstances, it is probable that for the last twelve months I have given as particular attention to the stage of the water in this river, as any other person in the country. In the month of March, 1831, in company with others, I commenced the building of a flat boat on the Sangamo, and finished and took her out in the course of the spring. Since that time, I have been concerned in the mill at New Salem. These circumstances are sufficient evidence, that I have not been very inattentive to the stages of the water….

…What the cost of this work would be, I am unable to say. It is probable, however, it would not be greater than is common to streams of the same length. Finally, I believe the improvement of the Sangamo river, to be vastly important and highly desirable to the people of this county; and if elected, any measure in the legislature having this for its object, which may appear judicious, will meet my approbation, and shall receive my support.

It appears that the practice of loaning money at exorbitant rates of interest, has already been opened as a field for discussion; so I suppose I may enter upon it without claiming the honor, or risking the danger, which may await its first explorer. It seems as though we are never to have an end to this baneful and corroding system, acting almost as prejudicial to the general interests of the community as a direct tax of several thousand dollars annually laid on each county, for the benefit of a few individuals only, unless there be a law made setting a limit to the rates of usury. A law for this purpose, I am of opinion, may be made, without materially injuring any class of people. In cases of extreme necessity there could always be means found to cheat the law, while in all other cases it would have its intended effect. I would not favor the passage of a law upon this subject, which might be very easily evaded. Let it be such that the labor and difficulty of evading it, could only be justified in cases of the greatest necessity.

Upon the subject of education, not presuming to dictate any plan or system respecting it, I can only say that I view it as the most important subject which we as a people can be engaged in. That every man may receive at least, a moderate education, and thereby be enabled to read the histories of his own and other countries, by which he may duly appreciate the value of our free institutions, appears to be an object of vital importance, even on this account alone, to say nothing of the advantages and satisfaction to be derived from all being able to read the scriptures and other works, both of a religious and moral nature, for themselves. For my part, I desire to see the time when education, and by its means, morality, sobriety, enterprise and industry, shall become much more general than at present, and should be gratified to have it in my power to contribute something to the advancement of any measure which might have a tendency to accelerate the happy period….

…But, Fellow-Citizens, I shall conclude. Considering the great degree of modesty which should always attend youth, it is probable I have already been more presuming than becomes me. However, upon the subjects of which I have treated, I have spoken as I thought. I may be wrong in regard to any or all of them; but holding it a sound maxim, that it is better to be only sometimes right, than at all times wrong, so soon as I discover my opinions to be erroneous, I shall be ready to renounce them.

Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition, is yet to be developed. I am young and unknown to many of you. I was born and have ever remained in the most humble walks of life. I have no wealthy or popular relations to recommend me. My case is thrown exclusively upon the independent voters of this county, and if elected they will have conferred a favor upon me, for which I shall be unremitting in my labors to compensate. But if the good people in their wisdom shall see fit to keep me in the background, I have been too familiar with disappointments to be very much chagrined.

Your friend and fellow-citizen,

New Salem, March 9, 1832.

A. LINCOLN.