DATELINE: WASHINGTON D.C., APRIL 18, 1848

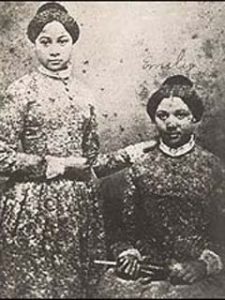

Mary and Emily Edmonson (Courtesy of Wikipedia)

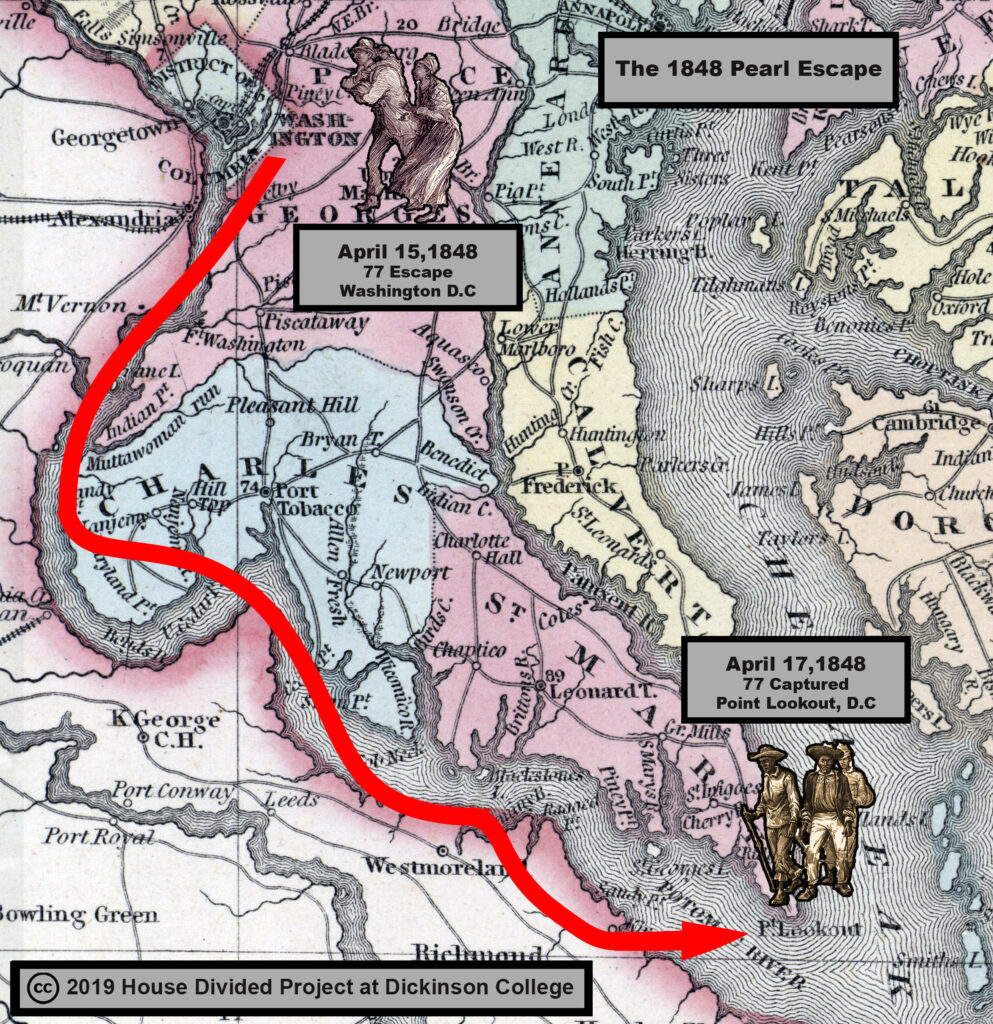

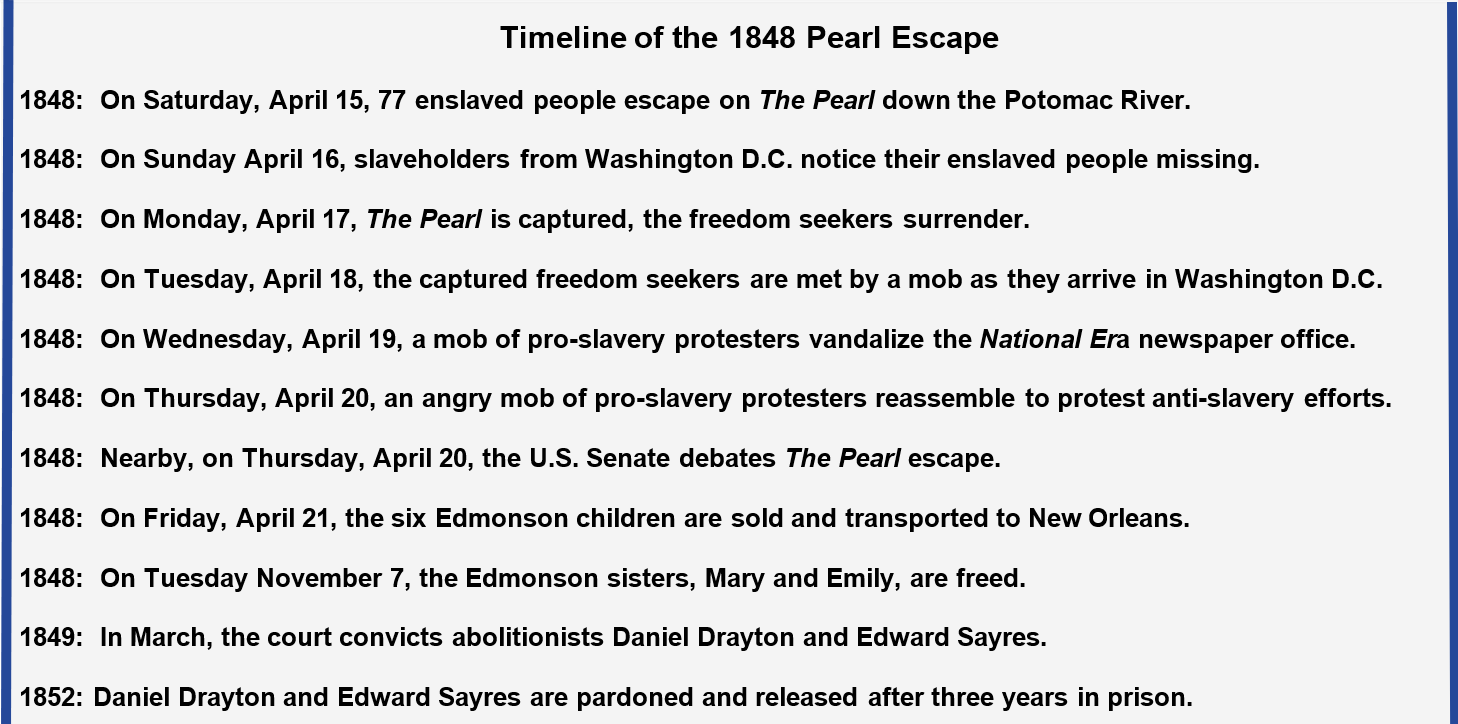

Daniel Drayton—captain of The Pearl—his accomplice Edward Sayres, and 77 freedom seekers fled Washington D.C on Saturday, April 15, 1848, in what Mary Kay Ricks describes as “one of history’s most audacious escapes.” [1] The goal of this escape was to sail from Washington D.C., down the Potomac River to freedom. [2] However, strong winds would disrupt their pursuit of freedom. [3] On April 18, 1848, The Pearl and its participants were captured.[4] After three days of being on the sea, Mary and Emily Edmonson—among 77 freedom seekers— returned home. Their new fate was what many freedom seekers feared most: being separated from their family and sold in the deep South.

Once back in Washington D.C., The Edmonson sisters and the other 75 freedom seekers—4 of whom were their brothers—walked through the mob of proslavery protesters, who anticipated their arrival.

While in jail, the sisters were separated from their brothers. [5] Knowing the tragic fate of the Edmonson children, a brother in law saw them, “fainted away, fell down, and was carried home insensible.” [6] Mary and Emily Edmonson’s free sister also tried to visit them, but could not enter the jail. Looking through the iron gates, Mary and Emily “saw their sister standing below in the yard weeping.”[7]

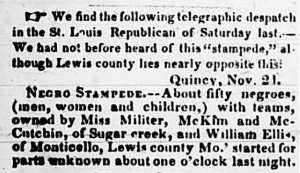

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

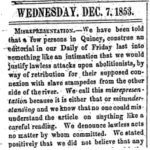

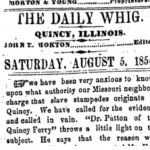

Historian Stanley Harrold calls the 1848 Pearl stampede the “most influential mass escape” in antebellum American history.[8] At first the escape was not explicitly referenced as a stampede. However, senators debating the event on nearby Capitol Hill made allusions to the Pearl escape using language that described the event as a mass escape. Shortly after the capture of the freedom seekers and during the riots incited by a proslavery mob, senators were forced to dispute the future of slavery in the District of Columbia. Referencing The Pearl, one pro-slavery senator from South Carolina, John C. Calhoun, denounced “these piratical attempts, these wholesale captures, these robberies of seventy-odd of our slaves at a single grasp.” [9] He even declared that “the crisis has come, and we must meet it, and meet it directly,” foreshadowing the debates over the Compromise of 1850. [10] Four years later, in the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, the term stampede appeared in the same column as the report of the pardoning of The Pearl participants Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres. The report read, “that in the border States, there is very frequently a stampede among the negroes – large number going off together.” One year later, when President Millard Fillmore –who had originally signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 into law– issued a pardon for the two abolitionists involved in the escape in 1853, a Georgia editor explained that they had been involved in “the great slave stampede.”[11]

MAIN NARRATIVE

On the evening of April 15, 1848, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres successfully left Washington D.C., setting sail down the Potomac River. Onboard The Pearl, Mary and Emily Edmonson were accompanied by their four brothers. After The Pearl’s departure, Captain Sayres decided to anchor in Cornfield Harbor, near Point Lookout, after strong winds did not allow them to “ascend the bay.” [12]

Back in Washington D.C, slaveholders noticed their enslaved people missing and frantically searched for them. The next day a steamboat—the Salem— departed from Washington D.C. in pursuit of The Pearl and the freedom seekers. Captained by Samuel Baker, the men on board the Salem were “armed with muskets and other weapons.” [13] Meanwhile, The Pearl was still anchored on the river.

On the morning of Monday, April 17, 1848, at around 2 am, the Salem finally caught The Pearl. [14] As the heavily armed men entered onboard, one of the Edmonson siblings reportedly said, “Do yourselves no harm, gentlemen, for we are all here!” [15] Overpowered, the freedom seekers surrendered without a fight and awaited their new fate.

Boston, MA Daily Atlas, April 22, 1848 (Genealogy Bank)

The next day, a large mob formed at the wharf in Washington D.C., awaiting the arrival of Edward Sayres, Daniel Drayton, and the captured freedom seekers. [16] As they walked off the boat, a report described “several small collections of blacks [with] tears rolling down many cheeks.” In particular, “one gray headed old woman” yelled, “O, my son, … must I see thee no more forever!” [17]

News of the capture caused pandemonium from the streets of Washington D.C. to the senate chambers on Capitol Hill. On the night of Wednesday, April 19, 1848, a mob of pro-slavery protesters “gathered at the National Era newspaper [an antislavery newspaper] office and threatened to destroy it.” [18] Simultaneously, a “heated debate” in Congress—sparked by the capture of The Pearl— occurred between pro-slavery and antislavery advocates about the future of slavery in Washington D.C. [19]

Shortly after Mary and Emily Edmonson’s escape attempt, their father Paul Edmonson solicited the help of abolitionist William Chaplin. Eventually, both men helped raise enough money to purchase the Edmonson sisters’ freedom. On Tuesday, November 7, Mary and Emily Edmonson were freed. [20] Their release gained national attention, as the Boston Daily Bee reported that the Edmonson sisters “were restored to liberty and their family. [21]

One year later, in March of 1849, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres were tried by the court for their participation in The Pearl escape. Both were found guilty and “convicted of transporting slaves on seventy-four separate indictments.” [22] However, after three years in prison for “not being able to pay the fines” for their conviction, President Fillmore pardoned them, granting their release. [23]

AFTERMATH

Newly freed Emily and Mary Edmonson joined the abolitionist movement. In 1850, they were most famously known for attending a public protest against the Fugitive Slave Act in Cazenovia, New York. [24] Eventually, both sisters seized the opportunity to become educated. They first moved to New York to enroll in Central College during the fall of 1851, and then went on to study at Oberlin College, with the help of abolitionist and writer Harriet Beecher Stowe. [25]

However, while studying at Oberlin College, Mary Edmonson—only twenty years old—died of tuberculosis. [26] After the death of her sister, Emily Edmonson left Oberlin to be with her family. Once settled at home in Washington D.C., Emily wrote to a family friend assuring them she was safe. Still mourning her sister’s death, Emily wrote, “Some days it seems as though I could not live without her… but when I think of how happy she is in heaven, I feel like wiping away all my tears.” [27]

Rochester, NY Frederick Douglass’ Paper, January 4, 1855 (Genealogy Bank)

Despite her sister’s passing, Emily Edmonson sustained her involvement in the antislavery movement, working closely with abolitionist Frederick Douglas. In his 1855 newspaper, it reported that Emily Edmonson gave a talk at Corinthian Hall about her experiences as an escapee on The Pearl. This abolitionist paper described her account as “new and thrilling” as people heard it “from the lips of one of the suffers.” [28]

Now older, Emily Edmonson married her husband Larkin Johnson and had four children— Emma, Ida, Fannie, and Robert. [29] Emily and her small knit family finally moved near the Anacostia River where she lived until her death on September 15th, 1895. [30] Today, a memorial statue of Mary and Emily Edmonson stands in Alexandria, Virginia as a constant reminder of their legacy.

[1] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 1

[2] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 30

[3] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 62

[4] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 82

[5] Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (B. Tauchnitz, 1853) 113: 2) [Google Books]

[6]Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (B. Tauchnitz, 1853) 112: 2) [Google Books]

[7] Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (B. Tauchnitz, 1853) 113: 2) [Google Books]

[9] Cong. Globe, 30th Cong., 1st sess., 501 (1848), accessible at American Memory Project, Library of Congress.

[10] Cong. Globe, 30th Cong., 1st sess., 502. (1848).

[11] “Insubordination of Negroes” Boston, MA The Liberator, October 1, 1852; “Reminiscences,” Macon (GA) Weekly Telegraph, August 2, 1853.

[12] Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton (New York: B. Marsh, 1855) 32

[13] “Capture of Runaway Slaves” Washington D.C. Daily Atlas, April 22, 1848

[14] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 78

[15] Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (B. Tauchnitz, 1853) 110: 2) [Google Books]

[16] 1848-04-22 Boston, MA Daily Atlas– Captured of Runaway Slaves [GB]

[17] New Lisbon, Ohio Anti-slavery bugle, May 5, 1848

[18] Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton (New York: B. Marsh, 1855) 42

[19] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 5

[20] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 195

[21] Boston, Massachusetts Boston Daily Bee, November 11, 1848

[22] House Executive Document, 34th Congress 1st Session (1855-1856) [WEB]

[23] House Executive Document, 34th Congress 1st Session (1855-1856) [WEB]

[24] “Edmonson Sisters”, women and the American Story, New York Historical Society [WEB]

[25] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 230, 236

[26] Samuel Momodu, “The Edmonson Sisters (1832-1895),” blackpast.org, September 28, 2016, [WEB]

[27] Emily Edmondson to Mr. and Mrs. Cowles, June 3, 1853, Henry Cowles Papers, Box #3, Record Group 30/27, Oberlin College Archives. [WEB]

[28] Rochester, New York Frederick Douglass’ Paper, April 01, 1855

[29] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 209

[30] Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: Passage to Freedom from Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2009) 349