Ranking

#80 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improves his workmanship. This improvement, he effects by Discoveries, and Inventions.”

On This Date

HD Daily Report, April 6, 1858

The Lincoln Log, April 6, 1858

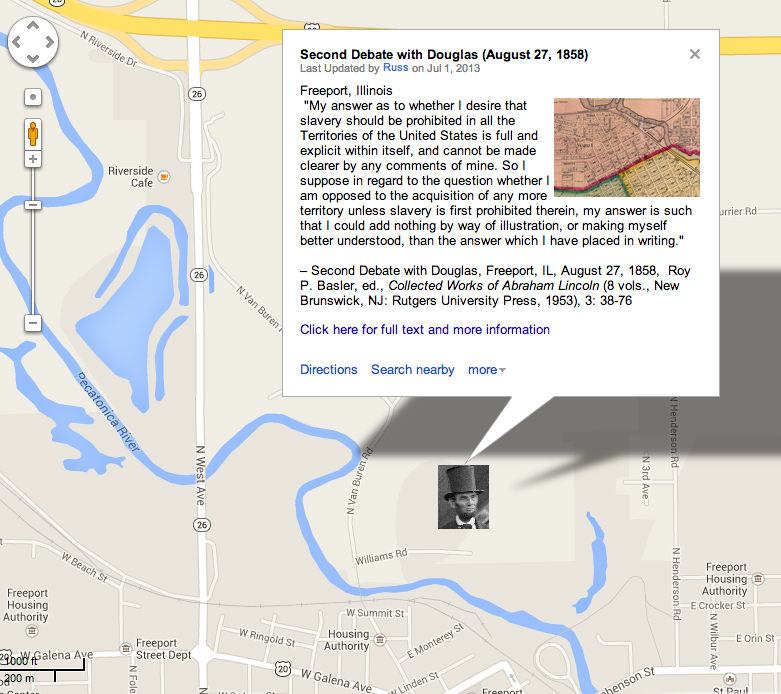

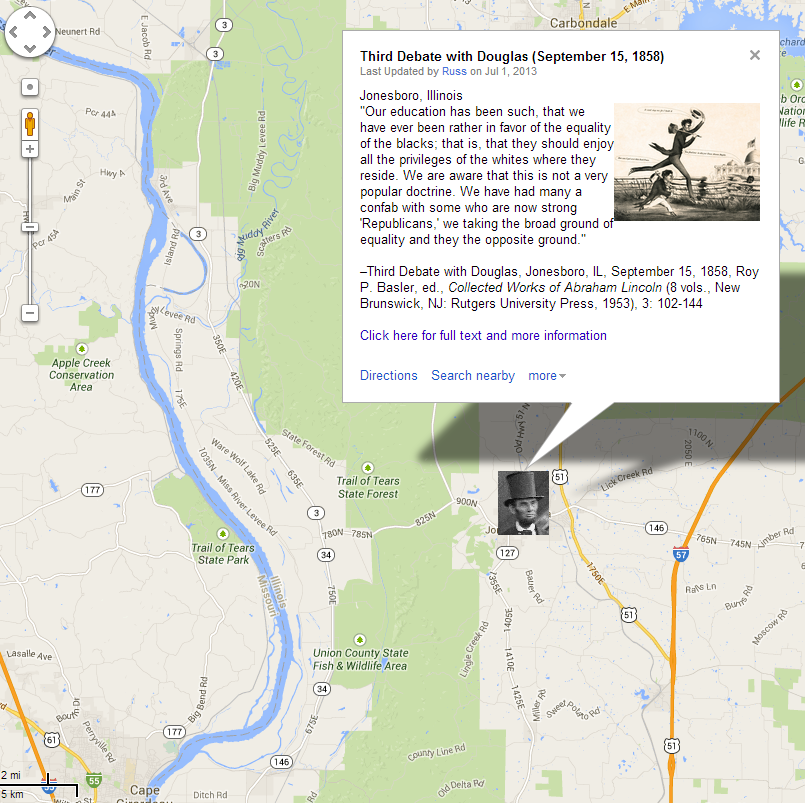

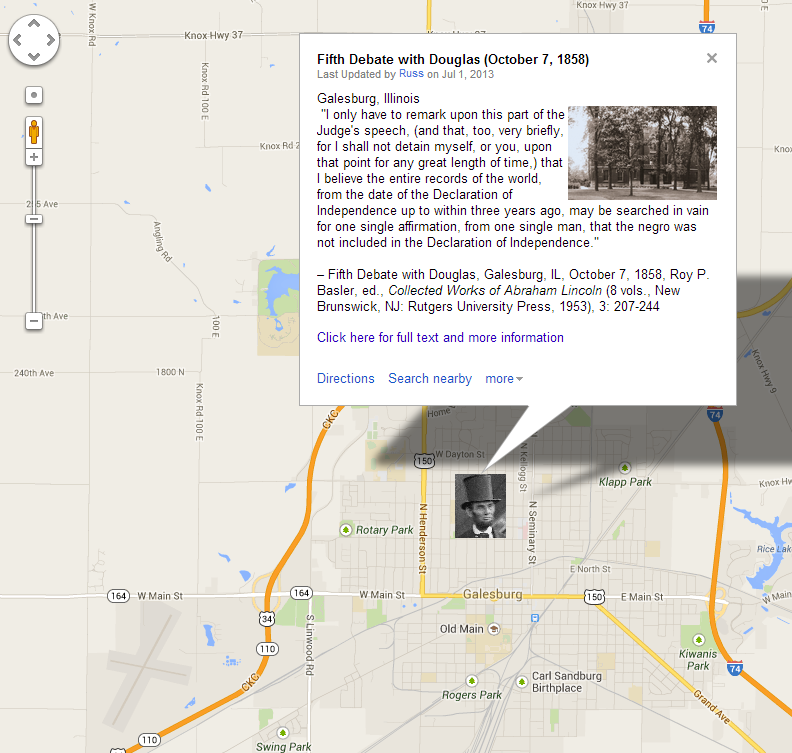

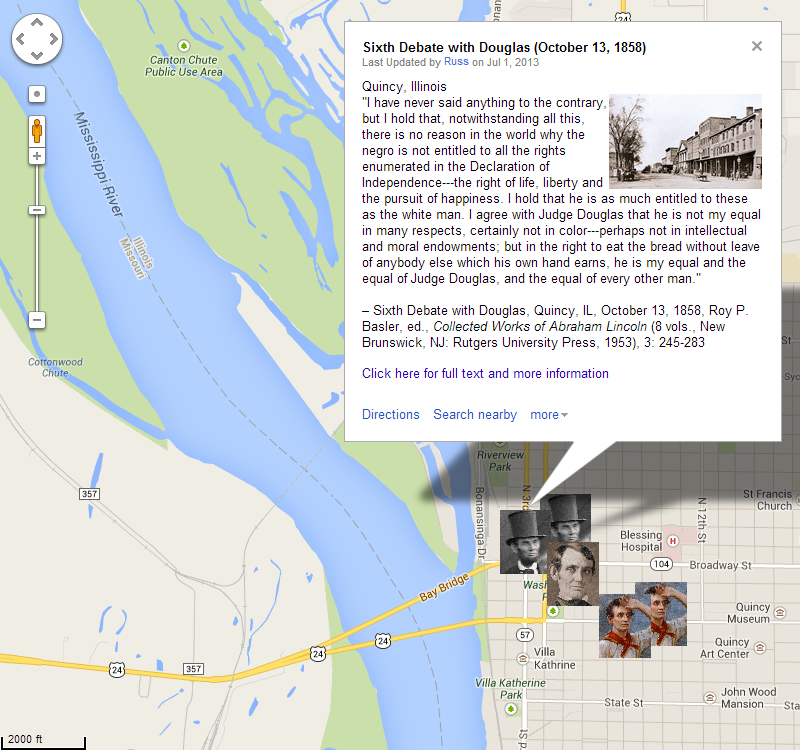

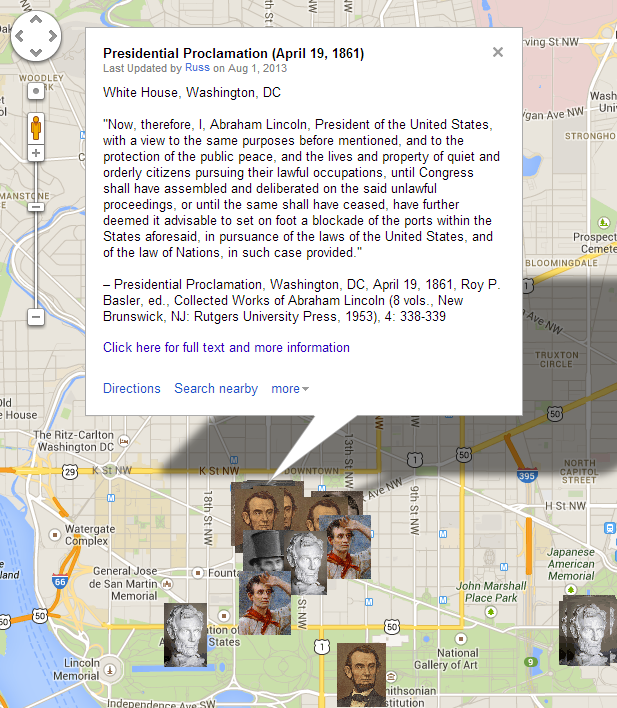

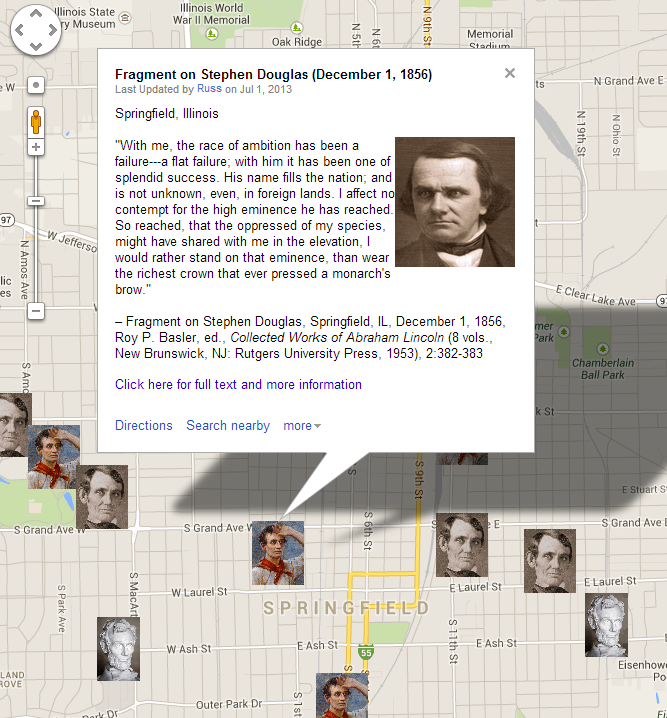

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

How Historians Interpret

“Many have dismissed the ‘First Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions,’ which is a historical ode to human ingenuity since Adam invented the fig-leaf apron. Many have explained it away as a caprice, an indulgence of Lincoln’s zany, nonconformist streak. But one distinguished biographer, J.G. Randall, in his Lincoln the President, decided the speech deserved a closer look. ‘In its of flow of sentences it marks Lincoln as something of a stylist, but that is secondary,’ according to Randall. ‘The main point is that in lecturing on discoveries and inventions he was thinking of enlightenment, of progress, down the centuries, of the emancipation of the mind . . .’ In a footnote, Randall adds, ‘Despite its unfavorable reception the lecture has meaning to one who would study the trends of Lincoln’s thought on the eve of his nomination to the presidency.’ Indeed, for anyone interested in Lincoln’s intellectual progress, all three of these speeches—the speech answering Douglas on June 26, 1857; the ‘First Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions,’ delivered on April 6, 1858; and finally the ‘House Divided’ speech on June 16, 1858—are crucial. For nearly two years the intriguing orator gave only these few addresses, and each shows us a different aspect of his mind.”

—Daniel Mark Epstein, Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington, (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2007), 30-31

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

All creation is a mine, and every man, a miner.

The whole earth, and all within it, upon it, and round about it, including himself, in his physical, moral, and intellectual nature, and his susceptabilities, are the infinitely various “leads” from which, man, from the first, was to dig out his destiny.

In the beginning, the mine was unopened, and the miner stood naked, and knowledgeless, upon it.

Fishes, birds, beasts, and creeping things, are not miners, but feeders and lodgers, merely. Beavers build houses; but they build them in nowise differently, or better now, than they did, five thousand years ago. Ants, and honey-bees, provide food for winter; but just in the same way they did, when Solomon refered the sluggard to them as patterns of prudence.

Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improves his workmanship. This improvement, he effects by Discoveries, and Inventions. His first important discovery was the fact that he was naked; and his first invention was the fig-leaf-apron. This simple article—the apron—made of leaves, seems to have been the origin of clothing—the one thing for which nearly half of the toil and care of the human race has ever since been expended. The most important improvement ever made in connection with clothing, was the invention of spinning and weaving. The spinning jenny, and power-loom, invented in modern times, though great improvements, do not, as inventions, rank with the ancient arts of spinning and weaving. Spinning and weaving brought into the department of clothing such abundance and variety of material. Wool, the hair of several species of animals, hemp, flax, cotten, silk, and perhaps other articles, were all suited to it, affording garments not only adapted to wet and dry, heat and cold, but also susceptable of high degrees of ornamental finish. Exactly when, or where, spinning and weaving originated is not known. At the first interview of the Almighty with Adam and Eve, after the fall, He made “coats of skins, and clothed them” Gen: 3-21.

The Bible makes no other alusion to clothing, before the flood. Soon after the deluge Noah’s two sons covered him with a garment; but of what material the garment was made is not mentioned. Gen. 9-23.

Abraham mentions “thread” in such connection as to indicate that spinning and weaving were in use in his day—Gen. 14.23— and soon after, reference to the art is frequently made. “Linen breeches, [”] are mentioned,—Exod. 28.42—and it is said “all the women that were wise hearted, did spin with their hands” (35-25) and, “all the women whose hearts stirred them up in wisdom, spun goat’s hair” (35-26). The work of the “weaver” is mentioned— (35-35). In the book of Job, a very old book, date not exactly known, the “weavers shuttle” is mentioned.

The above mention of “thread” by Abraham is the oldest recorded alusion to spinning and weaving; and it was made about two thousand years after the creation of man, and now, near four thousand years ago. Profane authors think these arts originated in Egypt; and this is not contradicted, or made improbable, by any thing in the Bible; for the alusion of Abraham, mentioned, was not made until after he had sojourned in Egypt.

The discovery of the properties of iron, and the making of iron tools, must have been among the earliest of important discoveries and inventions. We can scarcely conceive the possibility of making much of anything else, without the use of iron tools. Indeed, an iron hammer must have been very much needed to make the first iron hammer with. A stone probably served as a substitute. How could the “gopher wood” for the Ark, have been gotten out without an axe? It seems to me an axe, or a miracle, was indispensable. Corresponding with the prime necessity for iron, we find at least one very early notice of it. Tubal-cain was “an instructer of every artificer in brass and iron[”]—Gen: 4-22. Tubal-cain was the seventh in decent from Adam; and his birth was about one thousand years before the flood. After the flood, frequent mention is made of iron, and instruments made of iron. Thus “instrument of iron” at Num: 35-16; “bed-stead of iron” at Deut. 3-11—- “the iron furnace [”] at 4-20— and “iron tool” at 27-5. At 19-5— very distinct mention of “the ax to cut down the tree” is made; and also at 8-9, the promised land is described as “a land whose stones are iron, and out of whose hills thou mayest dig brass.” From the somewhat frequent mention of brass in connection with iron, it is not improbable that brass—perhaps what we now call copper—was used by the ancients for some of the same purposes as iron.

Transportation—the removal of person, and goods—from place to place—would be an early object, if not a necessity, with man. By his natural powers of locomotion, and without much assistance from Discovery and invention, he could move himself about with considerable facility; and even, could carry small burthens with him. But very soon he would wish to lessen the labor, while he might, at the same time, extend, and expedite the business. For this object, wheel-carriages, and water-crafts—wagons and boats—are the most important inventions. The use of the wheel & axle, has been so long known, that it is difficult, without reflection, to estimate it at it’s true value.

The oldest recorded allusion to the wheel and axle is the mention of a “chariot” Gen: 41-43. This was in Egypt, upon the occasion of Joseph being made Governor by Pharaoh. It was about twentyfive hundred years after the creation of Adam. That the chariot then mentioned was a wheel-carriage drawn by animals, is sufficiently evidenced by the mention of chariot-wheels, at Exod. 14-25, and the mention of chariots in connection with horses, in the same chapter, verses 9 & 23. So much, at present, for land-transportation.

Now, as to transportation by water, I have concluded, without sufficient authority perhaps, to use the term “boat” as a general name for all water-craft. The boat is indispensable to navigation. It is not probable that the philosophical principle upon which the use of the boat primarily depends—towit, the principle, that any thing will float, which can not sink without displacing more than it’s own weight of water—was known, or even thought of, before the first boats were made. The sight of a crow standing on a piece of drift-wood floating down the swolen current of a creek or river, might well enough suggest the specific idea to a savage, that he could himself get upon a log, or on two logs tied together, and somehow work his way to the opposite shore of the same stream. Such a suggestion, so taken, would be the birth of navigation; and such, not improbably, it really was. The leading idea was thus caught; and whatever came afterwards, were but improvements upon, and auxiliaries to, it.

As man is a land animal, it might be expected he would learn to travel by land somewhat earlier than he would by water. Still the crossing of streams, somewhat too deep for wading, would be an early necessity with him. If we pass by the Ark, which may be regarded as belonging rather to the miracalous, than to human invention the first notice we have of water-craft, is the mention of “ships” by Jacob—Gen: 49-13. It is not till we reach the book of Isaiah that we meet with the mention of “oars” and “sails.”

As mans food—his first necessity—was to be derived from the vegitation of the earth, it was natural that his first care should be directed to the assistance of that vegitation. And accordingly we find that, even before the fall, the man was put into the garden of Eden “to dress it, and to keep it.” And when afterwards, in consequence of the first transgression, labor was imposed on the race, as a penalty—a curse—we find the first born man—the first heir of the curse—was “a tiller of the ground.” This was the beginning of agriculture; and although, both in point of time, and of importance, it stands at the head of all branches of human industry, it has derived less direct advantage from Discovery and Invention, than almost any other. The plow, of very early origin; and reaping, and threshing, machines, of modern invention are, at this day, the principle improvements in agriculture. And even the oldest of these, the plow, could not have been conceived of, until a precedent conception had been caught, and put into practice—I mean the conception, or idea, of substituting other forces in nature, for man’s own muscular power. These other forces, as now used, are principally, the strength of animals, and the power of the wind, of running streams, and of steam.

Climbing upon the back of an animal, and making it carry us, might not, occur very readily. I think the back of the camel would never have suggested it. It was, however, a matter of vast importance.

The earliest instance of it mentioned, is when “Abraham rose up early in the morning, and saddled his ass,[”] Gen. 22-3 preparatory to sacraficing Isaac as a burnt-offering; but the allusion to the saddle indicates that riding had been in use some time; for it is quite probable they rode bare-backed awhile, at least, before they invented saddles.

The idea, being once conceived, of riding one species of animals, would soon be extended to others. Accordingly we find that when the servant of Abraham went in search of a wife for Isaac, he took ten camels with him; and, on his return trip, “Rebekah arose, and her damsels, and they rode upon the camels, and followed the man” Gen 24-61[.]

The horse, too, as a riding animal, is mentioned early. The Redsea being safely passed, Moses and the children of Israel sang to the Lord “the horse, and his rider hath he thrown into the sea.” Exo. 15-1.

Seeing that animals could bear man upon their backs, it would soon occur that they could also bear other burthens. Accordingly we find that Joseph’s bretheren, on their first visit to Egypt, “laded their asses with the corn, and departed thence” Gen. 42-26.

Also it would occur that animals could be made to draw burthens after them, as well as to bear them upon their backs; and hence plows and chariots came into use early enough to be often mentioned in the books of Moses—Deut. 22-10. Gen. 41-43. Gen. 46-29. Exo. 14-25[.]

Of all the forces of nature, I should think the wind contains the largest amount of motive power—that is, power to move things. Take any given space of the earth’s surface—for instance, Illinois—- and all the power exerted by all the men, and beasts, and running-water, and steam, over and upon it, shall not equal the one hundredth part of what is exerted by the blowing of the wind over and upon the same space. And yet it has not, so far in the world’s history, become proportionably valuable as a motive power. It is applied extensively, and advantageously, to sail-vessels in navigation. Add to this a few wind-mills, and pumps, and you have about all. That, as yet, no very successful mode of controlling, and directing the wind, has been discovered; and that, naturally, it moves by fits and starts—now so gently as to scarcely stir a leaf, and now so roughly as to level a forest—doubtless have been the insurmountable difficulties. As yet, the wind is an untamed, and unharnessed force; and quite possibly one of the greatest discoveries hereafter to be made, will be the taming, and harnessing of the wind. That the difficulties of controlling this power are very great is quite evident by the fact that they have already been perceived, and struggled with more than three thousand years; for that power was applied to sail-vessels, at least as early as the time of the prophet Isaiah.

In speaking of running streams, as a motive power, I mean it’s application to mills and other machinery by means of the “water wheel”—a thing now well known, and extensively used; but, of which, no mention is made in the bible, though it is thought to have been in use among the romans—(Am. Ency. tit—Mill) [.] The language of the Saviour “Two women shall be grinding at the mill &c” indicates that, even in the populous city of Jerusalem, at that day, mills were operated by hand—having, as yet had no other than human power applied to them.

The advantageous use of Steam-power is, unquestionably, a modern discovery.

And yet, as much as two thousand years ago the power of steam was not only observed, but an ingenius toy was actually made and put in motion by it, at Alexandria in Egypt.

What appears strange is, that neither the inventor of the toy, nor any one else, for so long a time afterwards, should perceive that steam would move useful machinery as well as a toy.