Contributing Editors for this page include Brian Elsner and Susan Segal

Ranking

#44 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

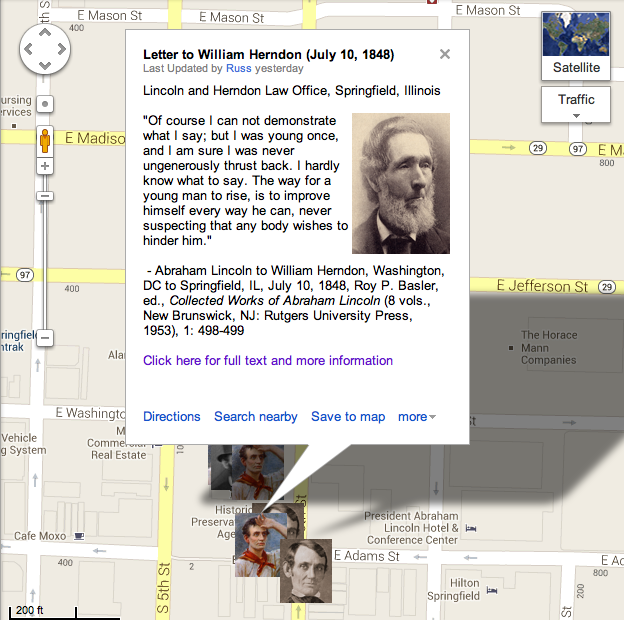

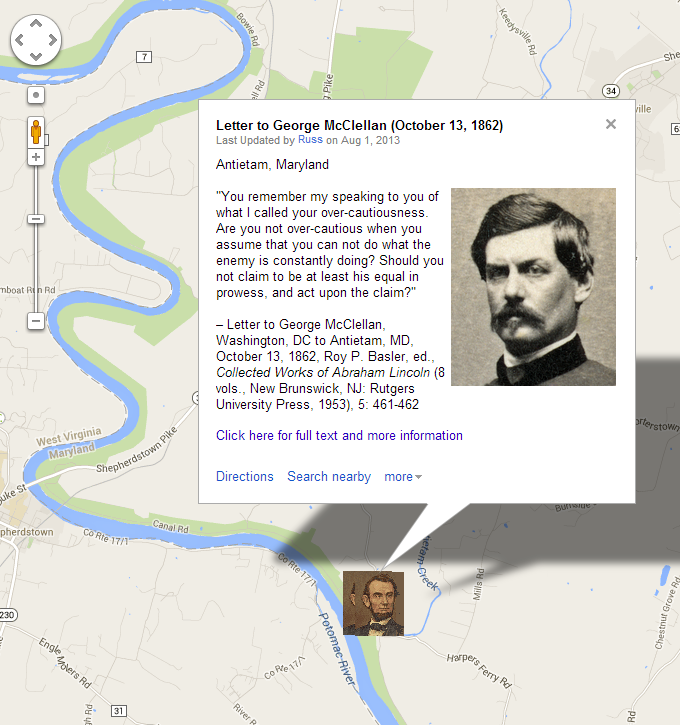

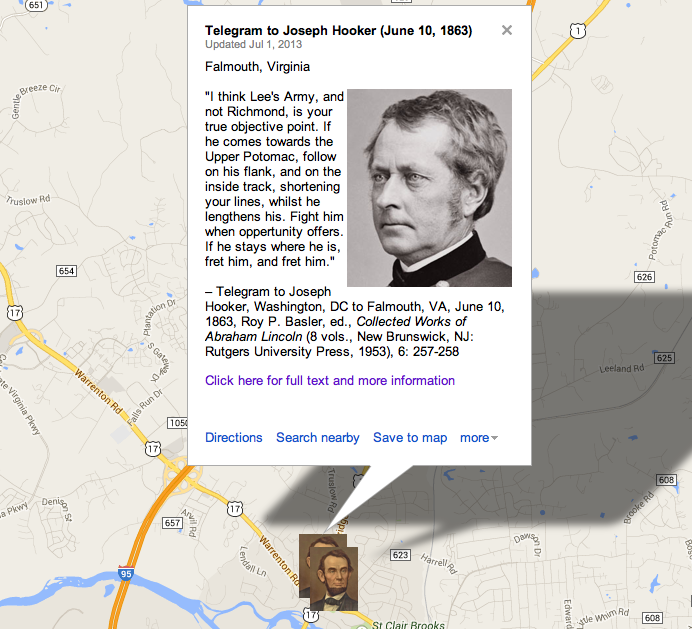

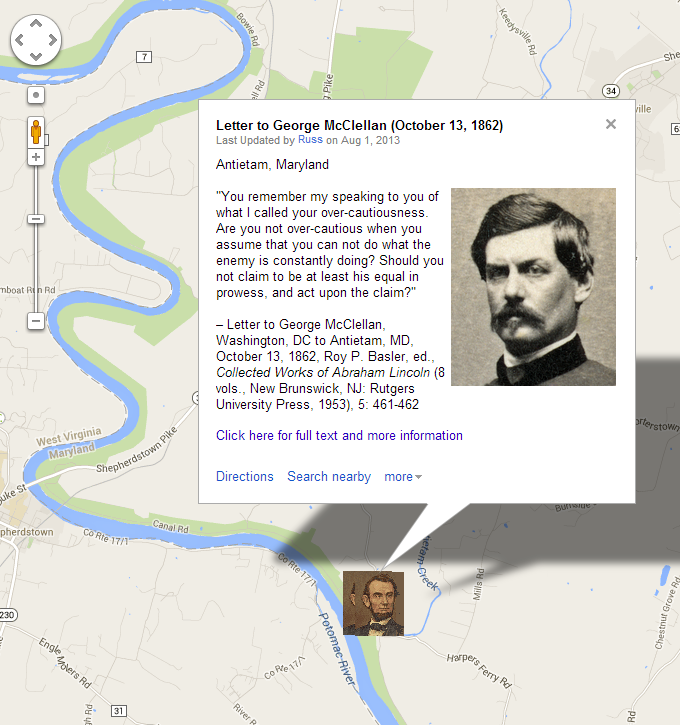

Context. George Brinton McClellan was appointed the Commander of the Army of the Potomac in 1861 and then General-in-Chief later that year. In March of 1862, he was removed as the General-in-Chief while he was away from Washington as part of the Peninsula Campaign. Then, on November 5, 1862, he was removed as Commander of the Army of the Potomac. Although McClellan was popular with the troops under his command, who called him “Little Mac,” he had vocal critics in the Republican-controlled Congress and President Lincoln had become increasingly frustrated with McClellan’s delays in pursuing the enemy. This letter from October 13, 1862, less than a month after the Union victory at Antietam (Sharpsburg), clearly illustrates that frustration. (By Susan Segal)

“Are you not over-cautious when you assume that you can not do what the enemy is constantly doing? Should you not claim to be at least his equal in prowess, and act upon the claim?”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, October 13, 1862

The Lincoln Log, October 13, 1862

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” participant Susan Segal, October 18, 2013. See also Segal’s blog post (via Quora), September 29, 2013

Brian Elsner, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), October 7, 2013

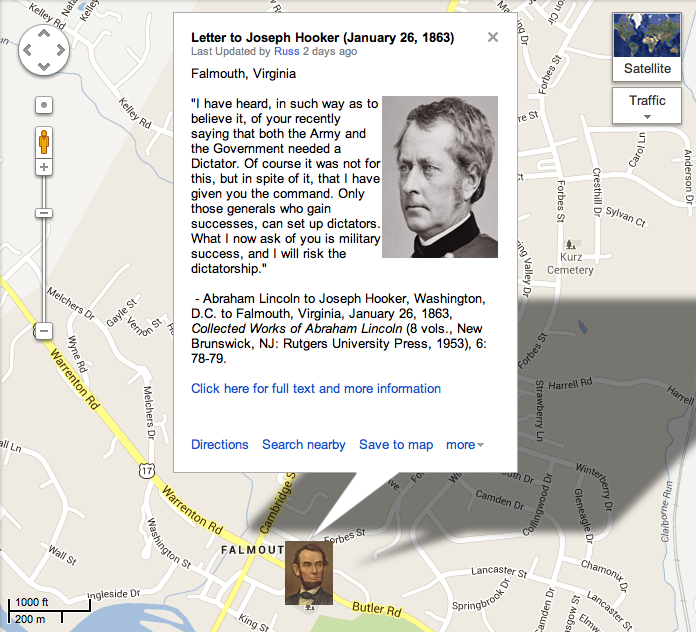

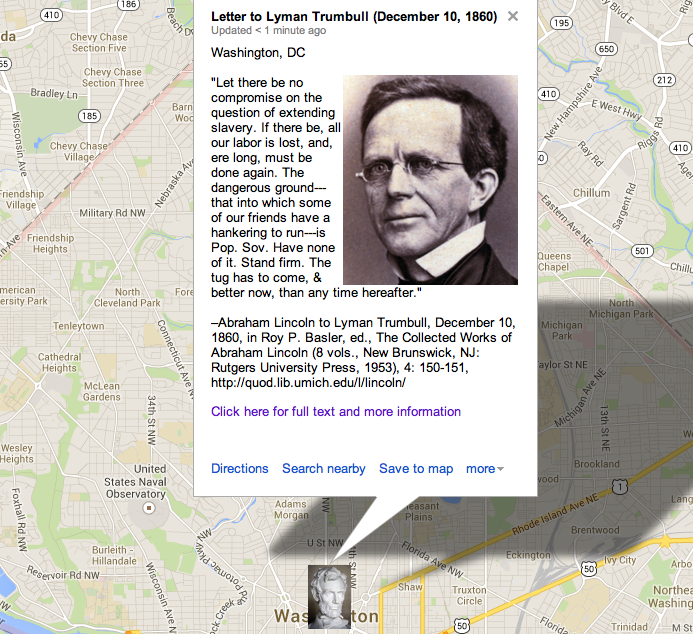

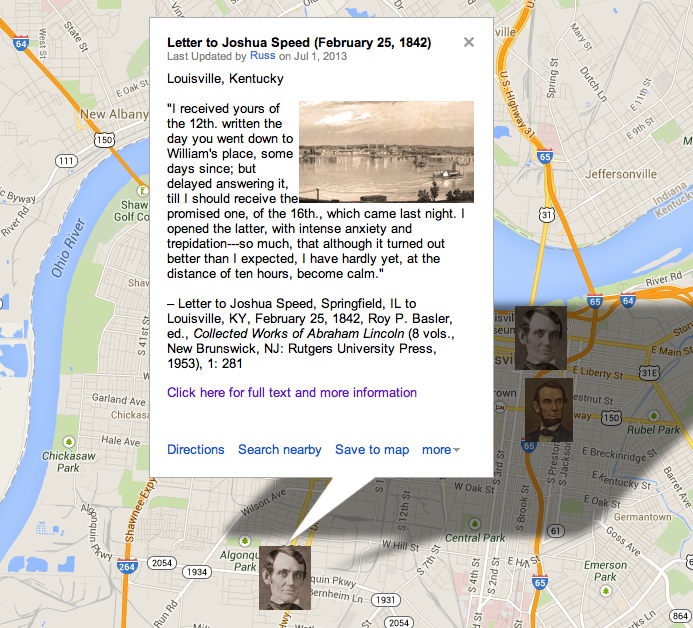

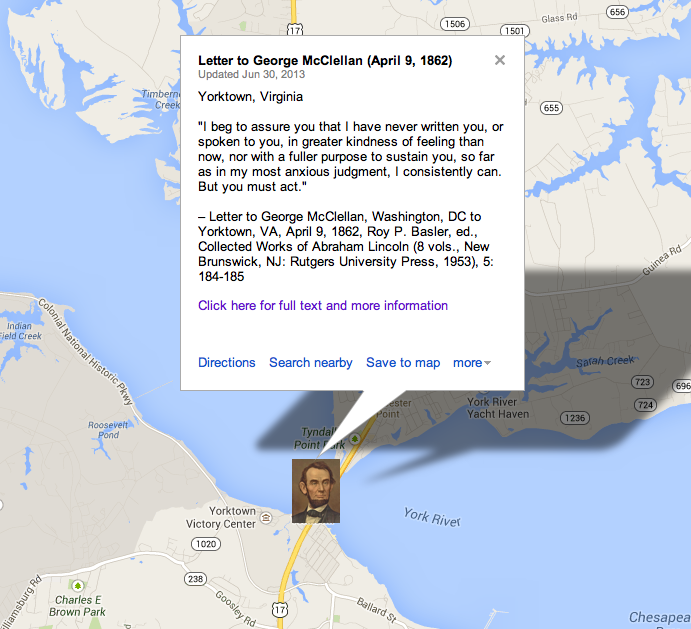

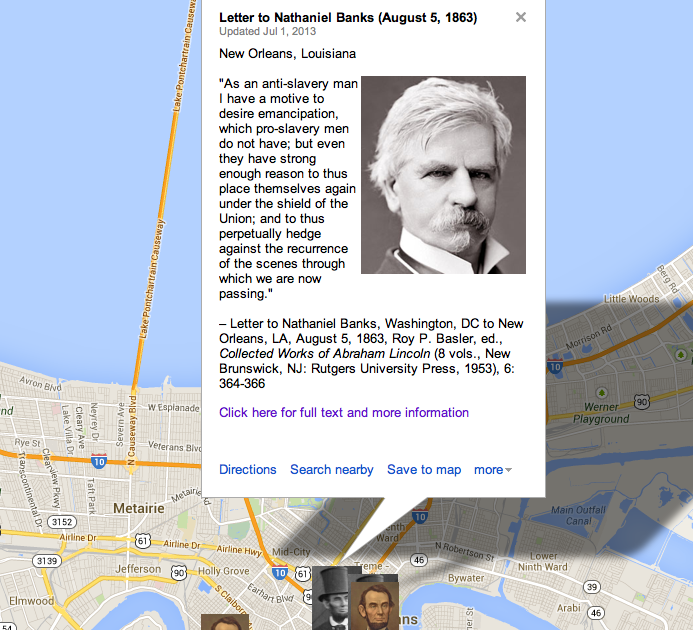

Custom Map

View in larger map

How Historians Interpret

“If Lee stayed put at Winchester, Lincoln urged, the Army of the Potomac should ‘fight him there, on the idea that if we can not beat him when he bears the wastage of coming to us, we never can when we bear the wastage of going to him. This proposition is a simple truth, and is too important to be lost sight of for a moment. In coming to us, he tenders us an advantage which we should not waive. We should not so operate as to merely drive him away. As we must beat him somewhere, or fail finally, we can do it, if at all, easier near to us, than far away. If we can not beat the enemy where he now is, we never can, he again being within the entrenchments of Richmond.’ After describing how the Union army could be easily supplied as it moved toward the Confederate capital, Lincoln assured Little Mac that his letter was ‘in no sense an order.’ Lincoln feared that this admonition would have little effect, even though it implicitly gave McClellan only one last chance to redeem himself.”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 29 (PDF), 3153.

“By failing to attack the enemy, McClellan had made too many personal enemies to remain much longer in command of the North’s foremost army. Lincoln wanted McClellan to get back across the Potomac and engage with Lee, but, as a delay followed delay, the frustration of both the president and the senior command reached breaking point. In mid-October, Lincoln wrote to McClellan, in one of the longest communications he ever sent to his general, setting out the situation as he saw it. He pointed out that ‘you are now nearer Richmond than the enemy is by the route that you can, and he must take. Why can you not reach there before him… his route is the arc of a circle, while yours is the chord. The roads are as good on yours as on his… If we cannot beat the enemy where he is now,’ Lincoln warned, ‘we never can.’ It was to no avail. Toward the end of the month, Lincoln’s patience was clearly running out.”

–Susan-Mary Grant, The War for a Nation (London: Routledge, 2006), 140.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

Executive Mansion, Washington, Oct. 13, 1862.

Major General McClellan

My dear Sir

You remember my speaking to you of what I called your over-cautiousness. Are you not over-cautious when you assume that you can not do what the enemy is constantly doing? Should you not claim to be at least his equal in prowess, and act upon the claim?

As I understand, you telegraph Gen. Halleck that you can not subsist your army at Winchester unless the Railroad from Harper’s Ferry to that point be put in working order. But the enemy does now subsist his army at Winchester at a distance nearly twice as great from railroad transportation as you would have to do without the railroad last named. He now wagons from Culpepper C.H. which is just about twice as far as you would have to do from Harper’s Ferry. He is certainly not more than half as well provided with wagons as you are. I certainly should be pleased for you to have the advantage of the Railroad from Harper’s Ferry to Winchester, but it wastes all the remainder of autumn to give it to you; and, in fact ignores the question of time, which can not, and must not be ignored.

Again, one of the standard maxims of war, as you know, is “to operate upon the enemy’s communications as much as possible without exposing your own.” You seem to act as if this applies against you, but can not apply in your favor. Change positions with the enemy, and think you not he would break your communication with Richmond within the next twentyfour hours? You dread his going into Pennsylvania. But if he does so in full force, he gives up his communications to you absolutely, and you have nothing to do but to follow, and ruin him; if he does so with less than full force, fall upon, and beat what is left behind all the easier.

Exclusive of the water line, you are now nearer Richmond than the enemy is by the route that you can, and he must take. Why can you not reach there before him, unless you admit that he is more than your equal on a march. His route is the arc of a circle, while yours is the chord. The roads are as good on yours as on his.

You know I desired, but did not order, you to cross the Potomac below, instead of above the Shenandoah and Blue Ridge. My idea was that this would at once menace the enemies’ communications, which I would seize if he would permit. If he should move Northward I would follow him closely, holding his communications. If he should prevent our seizing his communications, and move towards Richmond, I would press closely to him, fight him if a favorable opportunity should present, and, at least, try to beat him to Richmond on the inside track. I say “try”; if we never try, we shall never succeed. If he make a stand at Winchester, moving neither North or South, I would fight him there, on the idea that if we can not beat him when he bears the wastage of coming to us, we never can when we bear the wastage of going to him. This proposition is a simple truth, and is too important to be lost sight of for a moment. In coming to us, he tenders us an advantage which we should not waive. We should not so operate as to merely drive him away. As we must beat him somewhere, or fail finally, we can do it, if at all, easier near to us, than far away. If we can not beat the enemy where he now is, we never can, he again being within the entrenchments of Richmond.

Recurring to the idea of going to Richmond on the inside track, the facility of supplying from the side away from the enemy is remarkable—as it were, by the different spokes of a wheel extending from the hub towards the rim—and this whether you move directly by the chord, or on the inside arc, hugging the Blue Ridge more closely. The chord-line, as you see, carries you by Aldie, Hay-Market, and Fredericksburg; and you see how turn-pikes, railroads, and finally, the Potomac by Acquia Creek, meet you at all points from Washington. The same, only the lines lengthened a little, if you press closer to the Blue Ridge part of the way. The gaps through the Blue Ridge I understand to be about the following distances from Harper’s Ferry, towit: Vestal’s five miles; Gregorie’s, thirteen, Snicker’s eighteen, Ashby’s, twenty-eight, Mannassas, thirty-eight, Chester fortyfive, and Thornton’s fiftythree. I should think it preferable to take the route nearest the enemy, disabling him to make an important move without your knowledge, and compelling him to keep his forces together, for dread of you. The gaps would enable you to attack if you should wish. For a great part of the way, you would be practically between the enemy and both Washington and Richmond, enabling us to spare you the greatest number of troops from here. When at length, running for Richmond ahead of him enables him to move this way; if he does so, turn and attack him in rear. But I think he should be engaged long before such point is reached. It is all easy if our troops march as well as the enemy; and it is unmanly to say they can not do it.

This letter is in no sense an order.

Yours truly

A. LINCOLN