Ranking

#15 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

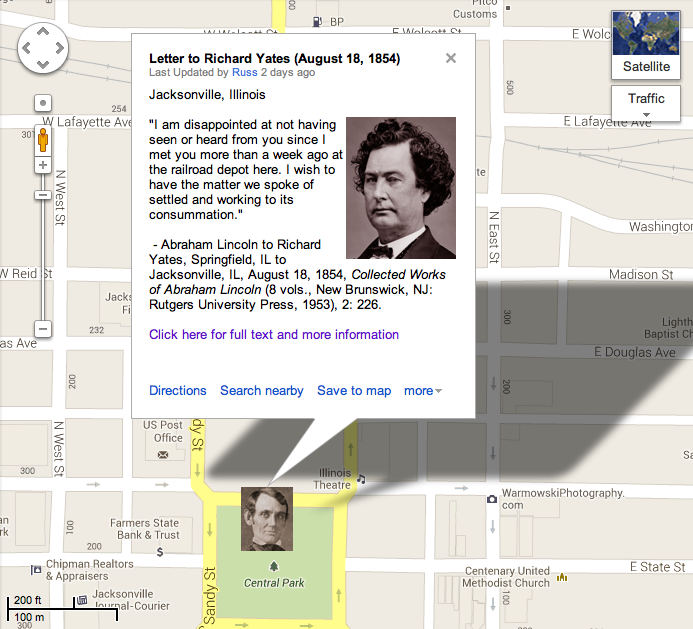

Context. In the summer of 1854, Abraham Lincoln was a 45-year-old attorney and former one-term US congressman living in Springfield, Illinois. However, in this letter to Richard Yates, his local congressman and fellow Whig, Lincoln acted and sounded more like a political party boss than anything else. He used this letter to organize Yates’s announcement for his campaign for reelection to Congress. Lincoln wanted to avoid holding a convention to secure Yates’s renomination because the partisan situation that summer was in turmoil, not only over the controversy surrounding the Kansas-Nebraska Act, but also because of the rise of anti-immigrant nativism. Lincoln made reference to coordinating with those so-called “Know Nothings,” in this letter by referring to their local leader, Benjamin S. Edwards, whom Lincoln deemed “entirely satisfied.” The newspapers did announce Yates’s availability the next week, though without mentioning the Whig Party label. He was ultimately defeated in the November 1854 midterm elections. (By Matthew Pinsker)

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, August 18, 1854

Image Gallery

- Lincoln in 1854

- Richard Yates

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Letter to Richard Yates (1854) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Abraham Lincoln to Richard J. Oglesby, Springfield, September 8, 1854

Abraham Lincoln to Richard Yates, Naples, October 30, 1854

Abraham Lincoln to Richard Yates, Naples, October 31, 1854

How Historians Interpret

“Feeling again the joy of political combat, he devoted all his time to the anti-Nebraska cause, except for his necessary commitments to court cases. He became, in effect, Yates’s campaign manager, spending hours conferring with the Whig candidate and advising him on tactics. Learning that English settlers in Morgan County were disturbed by reports that Yates was a Know-Nothing, he drafted a letter denying the charge, which could be distributed ‘at each precinct where any considerable number of the foreign citizens, german as well as english—vote.’ When he heard that Democrats were whispering that Yates, though professing to be a temperate man, was a secret drinker, he recognized that the rumor might cost the Whigs the large prohibitionist vote and sought to kill the allegation. ‘I have never seen him drink liquor, not act, or speak, as if he had been drinking, nor smelled it on his breath,’ he wrote. But then–almost as if he realized that the future would show that Yates did indulge in liquor, to the point of being intoxicated when he was inaugurated as governor of Illinois in 1861—Lincoln carefully explained his own position to a friend: ‘Other things being equal, I would much prefer a temperate man, to an intemperate one; still I do not make my vote depend absolutely upon the question of whether a candidate does or does not taste liquor.'”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 171

Further Reading

For educators:

Handout –Lincoln in 1854 (Pinsker)

Searchable Text

Jacksonville, Ill.