The Battle of Milliken’s Bend on June 7, 1863 was only a small part of the Vicksburg Campaign, but this engagement represented another important moment for African American participation in the Civil War. The three African American regiments, which had just been organized during the previous month, played an important part in the Confederate forces defeat. Victory, however, came at a high cost for those three regiments – almost 8% of the men who participated were killed. Yet as historian Richard Lowe observes, this battle “loom[ed] large in the overall history of the Civil War.” Even Confederates recognized the significance. “The obstinacy with which they fought…open the eyes of the Confederacy to the consequences” of the decision to allow African Americans to fight, as Confederate General John G. Walker recalled. Reports about the battle were published in newspapers across the country. While “at first [they] gave way,” the Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper made sure to note in their short summary that “the colored troops…[saw] their wounded massacred, rallied, and after one of the most deadly encounters in the war, drove the rebels back.” A letter published in Harper’s Weekly offered a similar account: “It was a genuine bayonet charge, a hand-to-hand fight, that has never occurred to any extent during this prolonged conflict.”

The Battle of Milliken’s Bend on June 7, 1863 was only a small part of the Vicksburg Campaign, but this engagement represented another important moment for African American participation in the Civil War. The three African American regiments, which had just been organized during the previous month, played an important part in the Confederate forces defeat. Victory, however, came at a high cost for those three regiments – almost 8% of the men who participated were killed. Yet as historian Richard Lowe observes, this battle “loom[ed] large in the overall history of the Civil War.” Even Confederates recognized the significance. “The obstinacy with which they fought…open the eyes of the Confederacy to the consequences” of the decision to allow African Americans to fight, as Confederate General John G. Walker recalled. Reports about the battle were published in newspapers across the country. While “at first [they] gave way,” the Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper made sure to note in their short summary that “the colored troops…[saw] their wounded massacred, rallied, and after one of the most deadly encounters in the war, drove the rebels back.” A letter published in Harper’s Weekly offered a similar account: “It was a genuine bayonet charge, a hand-to-hand fight, that has never occurred to any extent during this prolonged conflict.”

5

Apr

10

USCT at the Battle of Milliken’s Bend (June 7, 1863)

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals Themes: Battles & Soldiers2

Apr

10

“Flag Raising at Camp William Penn”

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals Themes: Battles & Soldiers This report appeared in the Boston Liberator in August 1863 and described the ceremony for the 3rd USCT regiment that took place at Camp William Penn. Even though this regiment was organized in “a comparatively short time,” the reporter believed that the men “[had] evinced a degree of enthusiasm and discipline that would do credit to older troops.” After a regiment drill “in which every evolution…was characterized by military correctness,” several speakers addressed the crowd. One noted that while “your enemies have said you would not fight,” the USCT “[has] already shown how base was that charge.” Another observed that in “this…war for freedom,” the 3rd USCT regiment “[would be] among the grandest of its soldiers.” You can read the entire article here.

This report appeared in the Boston Liberator in August 1863 and described the ceremony for the 3rd USCT regiment that took place at Camp William Penn. Even though this regiment was organized in “a comparatively short time,” the reporter believed that the men “[had] evinced a degree of enthusiasm and discipline that would do credit to older troops.” After a regiment drill “in which every evolution…was characterized by military correctness,” several speakers addressed the crowd. One noted that while “your enemies have said you would not fight,” the USCT “[has] already shown how base was that charge.” Another observed that in “this…war for freedom,” the 3rd USCT regiment “[would be] among the grandest of its soldiers.” You can read the entire article here.

26

Mar

10

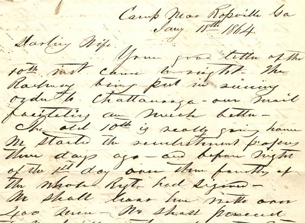

Captain Noah Hart Papers (1862-1865)

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals, Images, Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & SoldiersThe Noah Heart Papers at Dominican University offer an interesting perspective on the Civil War from a Union officer. Noah, who served with the 10th Michigan Infantry, wrote a number of letters to his wife, Emily, between 1862 and 1865. His regiment took part in several campaigns, including General William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea. While outside Atlanta in August 1864, Noah described one of the problems with his regiment’s supply chain. The 10th Michigan Infantry “lines of communication..are of immense length already,” and as Noah observed, “the farther we penetrate into the enemies country the more they become exposed.” “[If [the Confederates] should cut off our Cracker and Bacon line,” Noah concluded that “we would be in a pretty fix.” This collection also includes Noah’s military records, parts of Noah’s diary, newspaper clippings related to the Hart family (such as Noah’s obituary), and several photographs.

24

Mar

10

Railway Cars in Philadelphia

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals Themes: Battles & SoldiersPennsylvania Civil War Newspapers offers a great collection of historic newspapers published in cities across the state. This editorial from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin highlights that while those in the USCT were in the US Army, they did not enjoy the same rights and privileges as white soldiers. After a USCT surgeon was “ejected…[from a railway car] while on important public business” in Washington DC, the Evening Bulletin criticized the incident and explained how similar conditions existed in Philadelphia. “In New England all classes ride in the cars just as they mingle together in the same streets,” but in Philadelphia “the front platform of the car is the only place” where African Americans could ride. As a result, “men who have donned the uniform of the country and rallied to the defense of the old flag…[were] exposed to the wet and cold while half-drunken white men..loll upon the cushions inside.” While the Evening Bulletin proposed several solutions, those ideas included the introduction of segregated railcars rather than allow travelers to sit anywhere they wanted.

22

Mar

10

William Elisha Stoker: A Texas Farmer’s Civil War

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals, Images, Letters & DiariesListen to the essay

Editor’s Comments:

This essay was originally prepared for an exhibit co-sponsored by the National Civil War Museum in Harrisburg and available online at http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/stoker/

19

Mar

10

Becker Collection – Drawings of the American Civil War Era

Posted by sailerd Published in 19th Century (1840-1880), Images Themes: Battles & Soldiers The Becker Collection is a great digital project from Boston College that contains over 600 drawings by Joseph Becker and others who worked for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. The “Featured Images” slideshow provides a nice introduction to what is available in the collection. These drawings cover a range of Civil War related topics, such as camp life, military ceremonies and discipline, panoramas and landscapes, and ships. Other topics include the Chicago fire, political cartoons, and the Trans-Atlantic cable. Biographies of the artists featured in this collection are also available.

The Becker Collection is a great digital project from Boston College that contains over 600 drawings by Joseph Becker and others who worked for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly. The “Featured Images” slideshow provides a nice introduction to what is available in the collection. These drawings cover a range of Civil War related topics, such as camp life, military ceremonies and discipline, panoramas and landscapes, and ships. Other topics include the Chicago fire, political cartoons, and the Trans-Atlantic cable. Biographies of the artists featured in this collection are also available.

17

Mar

10

Western History – Historic Images

Posted by sailerd Published in 19th Century (1840-1880), Images Themes: Battles & Soldiers, Settlers & Immigrants The Denver Public Library has a nice digital collection of images related to various topics in Western history. While not available to download for free, each set of images can still be viewed as a slideshow – these include “Railroads,” “On the Trail and Covered Wagon,” “Western Life,” and “Wild West Shows.” Other digital collections from the Denver Public Library are available here.

The Denver Public Library has a nice digital collection of images related to various topics in Western history. While not available to download for free, each set of images can still be viewed as a slideshow – these include “Railroads,” “On the Trail and Covered Wagon,” “Western Life,” and “Wild West Shows.” Other digital collections from the Denver Public Library are available here.

16

Mar

10

Two Communities during the Election of 1860

Posted by Published in 19th Century (1840-1880), Lesson Plans, Rare Books Themes: Contests & ElectionsWilliam G. Thomas III and Edward L. Ayers have a piece of digital scholarship entitled  “The Differences Slavery Made: A Close Analysis of Two American Communities” that analyzes Augusta County, Virginia and Franklin County, Pennsylvania in the period just before the Civil War. While the scope of the article is to relate how slavery affected these two small communities, it contains some important analysis of the election of 1860 as well. The method follows closely that used by Ayers in his excellent book In the Presence of Mine Enemies. Analyzing primary documents from these two small towns close to the Mason-Dixon line sheds new light on previously held notions of how the buildup to the Civil War affected everyday Americans. Of particular interest in this article is the summary of Politics and the Election of 1860 and the “points of analysis” from these towns in the Campaign of 1860 and the Election of 1860. The digital format of this article makes it particularly compelling as the authors’ points about each county can be summarized briefly in a side-by-side manner, and then expanded upon by clicking the link if more information is needed. In this expanded view of the argument, there are links to all of the supporting evidence and historiography at the bottom.

“The Differences Slavery Made: A Close Analysis of Two American Communities” that analyzes Augusta County, Virginia and Franklin County, Pennsylvania in the period just before the Civil War. While the scope of the article is to relate how slavery affected these two small communities, it contains some important analysis of the election of 1860 as well. The method follows closely that used by Ayers in his excellent book In the Presence of Mine Enemies. Analyzing primary documents from these two small towns close to the Mason-Dixon line sheds new light on previously held notions of how the buildup to the Civil War affected everyday Americans. Of particular interest in this article is the summary of Politics and the Election of 1860 and the “points of analysis” from these towns in the Campaign of 1860 and the Election of 1860. The digital format of this article makes it particularly compelling as the authors’ points about each county can be summarized briefly in a side-by-side manner, and then expanded upon by clicking the link if more information is needed. In this expanded view of the argument, there are links to all of the supporting evidence and historiography at the bottom.

9

Mar

10

Papers of Jefferson Davis

Posted by Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Contests & Elections Rice University’s project The Papers of Jefferson Davis has been blogged about earlier, but there are two documents relevant to the Election of 1860 that I wanted to point out. The project is an attempt to compile all of Davis’s documents into a 15-volume set (twelve of which has been published so far), and in the process some of the important letters and speeches have been digitized as well. Volume 6 of the collection contains materials from the years 1856-1860, particularly two important documents from 1860: an Address to the National Democracy in May 1860 and a speech from Washington, D.C. in July 1860. The first document is a summary of the events of the Democratic National Convention that took place in Charleston and resulted in the splitting of the party into two factions over the slavery issue. Davis actually praises the “lofty manifestation of adherence to principle” displayed on the part of the Southern delegates who withdrew from the convention, but insists that if the demands of the Southern delegates are met during the new Baltimore convention “no motive will remain for refusing to unite with their sister States.” He appears to believe that the demands of the Southern “fire-eaters” may still be met by the other half of the Democratic party, and the party can unite once again in time for the election. The address urges Southern democrats to await the outcome of the Baltimore convention before holding their own convention in Richmond, and was affirmed by 18 members of Congress. Jefferson Davis’s speech from Washington, D.C. in July of 1860 presents a markedly different tone. The speech is short, but it sends the powerful message that although the Democratic party is split, it is not dead. He contrasts the Southern Democratic party with the other three parties, calling the Northern Democrats a “spurious and decayed off-shoot of democracy,” and bemoaning “Abe Lincoln’s efforts to rend the Union.” Finally he endorses John Breckinridge for president, declaring that “he has split a hundred rails to Lincoln’s one!” These two primary documents demonstrate the progression of the splitting of the Democratic party in a very clear way, from the hopeful moment that the party can again unify to the finality of the factions nominating different candidates for president.

Rice University’s project The Papers of Jefferson Davis has been blogged about earlier, but there are two documents relevant to the Election of 1860 that I wanted to point out. The project is an attempt to compile all of Davis’s documents into a 15-volume set (twelve of which has been published so far), and in the process some of the important letters and speeches have been digitized as well. Volume 6 of the collection contains materials from the years 1856-1860, particularly two important documents from 1860: an Address to the National Democracy in May 1860 and a speech from Washington, D.C. in July 1860. The first document is a summary of the events of the Democratic National Convention that took place in Charleston and resulted in the splitting of the party into two factions over the slavery issue. Davis actually praises the “lofty manifestation of adherence to principle” displayed on the part of the Southern delegates who withdrew from the convention, but insists that if the demands of the Southern delegates are met during the new Baltimore convention “no motive will remain for refusing to unite with their sister States.” He appears to believe that the demands of the Southern “fire-eaters” may still be met by the other half of the Democratic party, and the party can unite once again in time for the election. The address urges Southern democrats to await the outcome of the Baltimore convention before holding their own convention in Richmond, and was affirmed by 18 members of Congress. Jefferson Davis’s speech from Washington, D.C. in July of 1860 presents a markedly different tone. The speech is short, but it sends the powerful message that although the Democratic party is split, it is not dead. He contrasts the Southern Democratic party with the other three parties, calling the Northern Democrats a “spurious and decayed off-shoot of democracy,” and bemoaning “Abe Lincoln’s efforts to rend the Union.” Finally he endorses John Breckinridge for president, declaring that “he has split a hundred rails to Lincoln’s one!” These two primary documents demonstrate the progression of the splitting of the Democratic party in a very clear way, from the hopeful moment that the party can again unify to the finality of the factions nominating different candidates for president.

8

Mar

10

“A Civil War Soldier in the Wild Cat Regiment”

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & Soldiers“A Civil War Soldier in the Wild Cat Regiment,” which is available from the Library of Congress, features Captain Tilton Reynolds correspondence with his family between 1861 and 1864. Reynolds, who joined the 105th Pennsylvania Volunteers as a seventeen year old private, became a prisoner of war after the Battle of Fair Oaks in May 1862 and was exchanged four months later. Hereceived a commission in November 1864. (A timeline is available). Forty-six letters in this collection have been transcribed, including one from October 1861 in which Reynolds described President Abraham Lincoln. As “President Lincoln and his Wife and child went By In a two horse Carriage,” Reynolds explained how “Lincoln laughed when he seen us all standing looking at him.” “[Lincoln] looks a good deal like his picture only he is better looking,” as Reynolds concluded. In addition, this exhibit includes correspondence from other members of Reynolds’ extended family as well as from a family friend who also served in the Wild Cat Regiment. A short essay provides more information on these individuals.

Search

Administration

Recent Post

- Black Employees and Exclusive Spaces: The Dickinson Campus in the Late 19th Century

- Friend or Foe: Nineteenth Century Dickinson College Students’ Perception of Their Janitors

- Teaching Gettysburg: New Classroom Resources

- Coverage of the Gettysburg Address

- Welcome to Chicago: Choosing the Right Citation Generator

- Augmented Reality in the Classroom

- Beyond Gettysburg: Primary Sources for the Gettysburg Campaign

- African Americans Buried at Gettysburg

- The Slave Hunt: Amos Barnes and Confederate Policy

- Entering Oz – Bringing Color to History

Recent Comments

- George Georgiev in Making Something to Write Home About

- Matthew Pinsker in The Slave Hunt: Amos Barnes and Confederate Policy…

- linard johnson in Making Something to Write Home About

- Bedava in The Slave Hunt: Amos Barnes and Confederate Policy…

- Adeyinka in Discovering the Story of a Slave Catcher

- Stefan Papp Jr. in Where was William Lloyd Garrison?

- Stefan Papp Jr. in Where was William Lloyd Garrison?

- Jon White in Albert Hazlett - Trial in Carlisle, October 1859

- Pedro in Discovering the Story of a Slave Catcher

- Matthew Pinsker in Register Today for "Understanding Lincoln," a New …