Before going to bed on October 10, 1862, Chambersburg resident William Heyser noted in his diary that he had “secreted some of my most valuable papers.” Confederate cavalry under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart had arrived several hours earlier and forced the town to surrender. Union forces had been caught by surprise and none were available to defend the town. “It would have been an act of madness to have made resistance…and would have involved the total destruction of the town,” as the Chambersburg (PA) Valley Spirit noted. The raid, as the Milwaukee (WI) Sentienel described, “was the most daring adventure of the war” so far. Besides gathering intelligence, one of the Confederate’s other objectives was to take as many supplies as possible. Horses were one key item and Alexander Kelly McClure, an assistant adjutant Union general, later recalled how ten horses were taken from his farm. (You can read McClure’s full account of the Confederate raid – “A Night With Stuart’s Raiders”- here). Yet as one Confederate soldier’s letter revealed, they also seized a number of other supplies. “I got 8 pair of boots, 4 over coats, 5 pair of pantaloons, 2 hats, 6 pair of socks, 6 pr. Draws, 6 over & under shirts, [and] some coffe & sugar” during the raid, as Edward Cottrell told his grandmother. As Confederates left Chambersburg on October 11, they burned warehouses that held government supplies. One contained ammunition and, as Heyser described, “the succeeding explosions of shells and power was tremendous.” While Union forces were dispatched to intercept and capture the raiders, General Stuart evaded them and returned to Virginia without any major engagements. You can read more about the raid in Emory M. Thomas’ Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (1986) and Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (2008).

Before going to bed on October 10, 1862, Chambersburg resident William Heyser noted in his diary that he had “secreted some of my most valuable papers.” Confederate cavalry under the command of General J. E. B. Stuart had arrived several hours earlier and forced the town to surrender. Union forces had been caught by surprise and none were available to defend the town. “It would have been an act of madness to have made resistance…and would have involved the total destruction of the town,” as the Chambersburg (PA) Valley Spirit noted. The raid, as the Milwaukee (WI) Sentienel described, “was the most daring adventure of the war” so far. Besides gathering intelligence, one of the Confederate’s other objectives was to take as many supplies as possible. Horses were one key item and Alexander Kelly McClure, an assistant adjutant Union general, later recalled how ten horses were taken from his farm. (You can read McClure’s full account of the Confederate raid – “A Night With Stuart’s Raiders”- here). Yet as one Confederate soldier’s letter revealed, they also seized a number of other supplies. “I got 8 pair of boots, 4 over coats, 5 pair of pantaloons, 2 hats, 6 pair of socks, 6 pr. Draws, 6 over & under shirts, [and] some coffe & sugar” during the raid, as Edward Cottrell told his grandmother. As Confederates left Chambersburg on October 11, they burned warehouses that held government supplies. One contained ammunition and, as Heyser described, “the succeeding explosions of shells and power was tremendous.” While Union forces were dispatched to intercept and capture the raiders, General Stuart evaded them and returned to Virginia without any major engagements. You can read more about the raid in Emory M. Thomas’ Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (1986) and Jeffry D. Wert’s Cavalryman of the Lost Cause: A Biography of J. E. B. Stuart (2008).

30

Jul

10

Confederate raid on Chambersburg, Pennsylvania (October 1862)

Posted by sailerd Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals, Images, Letters & Diaries Themes: Battles & Soldiers28

Jul

10

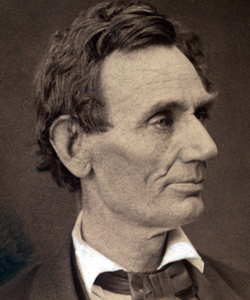

Election of 1860 – Southerners Unionists

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Contests & Elections While some southern editors argued before election day in November 1860 that a Republican victory would justify secession, the Fayetteville (NC) Observer was prepared to accept Abraham Lincoln as President. The Observer, which supported Constitutional Union candidates John Bell and Edward Everett, believed that there was no choice but to accept the results of an election that they participated in. If “[it was] decided constitutionally,” the Observer explainedthat “we [were] honor bound to abide its results.” Southerners who threatened to secede only created more problems, particularly those who were not prepared to follow through with their threats. “We have had enough of ultimatum-manufacturing,” as the Observer noted. Those southerners had a bad “habit of invariably back out after” issuing ultimatums and, as the Observer argued, the repeated false alarms “[had] made the North believe that the South cannot be kicked out of the Union.” This scenario was dangerous since the Observer, like other unionist papers, did not completely reject secession as an option. If President Lincoln took any action that they considered a threat to slavery, many would support disunion. For the Observer and other ‘conditional’ unionists, the turning point was President Lincoln’s call for volunteers after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861. One of the best sources on southern unionists’ perspectives during this period is Daniel W. Crofts’ Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (1989). While Crofts discusses the Upper South, Edward Ayers focuses on southern unionists Augusta County, Virginia in In the Presence of Mine Enemies: War in the Heart of America, 1859-1863 (2003). You can learn more about that community online at the Valley of the Shadow project.

While some southern editors argued before election day in November 1860 that a Republican victory would justify secession, the Fayetteville (NC) Observer was prepared to accept Abraham Lincoln as President. The Observer, which supported Constitutional Union candidates John Bell and Edward Everett, believed that there was no choice but to accept the results of an election that they participated in. If “[it was] decided constitutionally,” the Observer explainedthat “we [were] honor bound to abide its results.” Southerners who threatened to secede only created more problems, particularly those who were not prepared to follow through with their threats. “We have had enough of ultimatum-manufacturing,” as the Observer noted. Those southerners had a bad “habit of invariably back out after” issuing ultimatums and, as the Observer argued, the repeated false alarms “[had] made the North believe that the South cannot be kicked out of the Union.” This scenario was dangerous since the Observer, like other unionist papers, did not completely reject secession as an option. If President Lincoln took any action that they considered a threat to slavery, many would support disunion. For the Observer and other ‘conditional’ unionists, the turning point was President Lincoln’s call for volunteers after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861. One of the best sources on southern unionists’ perspectives during this period is Daniel W. Crofts’ Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (1989). While Crofts discusses the Upper South, Edward Ayers focuses on southern unionists Augusta County, Virginia in In the Presence of Mine Enemies: War in the Heart of America, 1859-1863 (2003). You can learn more about that community online at the Valley of the Shadow project.

28

Jul

10

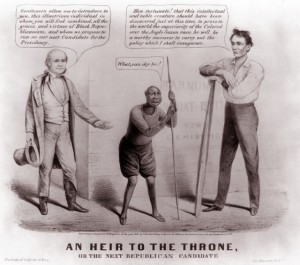

Partisan Fear-mongering in 1860

Posted by Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Images After what could only be mildly described as a tumultuous decade of failed compromises, the rise of a new political party, and a disgruntled citizenry, the 1860 Election season met with the pronounced fears over the future course of the United States. Partisan newspapers relished the opportunity to hack away at their opponents by castigating their political views and theorizing on pressing social fears within the South. The Chicago Press and Tribune noted that the “slave breeders” of the South feared a Republican party in their midst that could claim Founders as part of its political pedigree. The article also cites an undated piece from the New Orleans Courier which speculated that if Republicans proved victorious in the upcoming election, Southerners would have to openly embrace the patronage positions offered them as members of a new Southern Republican “nucleus.” (Ironically, Lincoln and his cabinet maintained their hope in a latent Southern Unionism in Virginia that would dissuade the Upper South from seceding.) Other fears for the upcoming election literally struck at the belly of the South. Again, the Chicago Press and Tribune stated that a “poor corn-crop” would precede a potential famine in the upcoming year. Instead of stoking this fear in their hearts, Southerners could remain “patriots and good citizens’ by “behaving themselves” in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election. However, the Press and Tribune cynically mused that the “dissolution” of the Union would only be averted until the South had a “full crop.” Articles in partisan papers such as the Chicago Press and Tribune reveal the broad spectrum of fears endemic to the United States in the months leading up to the Election of 1860.

After what could only be mildly described as a tumultuous decade of failed compromises, the rise of a new political party, and a disgruntled citizenry, the 1860 Election season met with the pronounced fears over the future course of the United States. Partisan newspapers relished the opportunity to hack away at their opponents by castigating their political views and theorizing on pressing social fears within the South. The Chicago Press and Tribune noted that the “slave breeders” of the South feared a Republican party in their midst that could claim Founders as part of its political pedigree. The article also cites an undated piece from the New Orleans Courier which speculated that if Republicans proved victorious in the upcoming election, Southerners would have to openly embrace the patronage positions offered them as members of a new Southern Republican “nucleus.” (Ironically, Lincoln and his cabinet maintained their hope in a latent Southern Unionism in Virginia that would dissuade the Upper South from seceding.) Other fears for the upcoming election literally struck at the belly of the South. Again, the Chicago Press and Tribune stated that a “poor corn-crop” would precede a potential famine in the upcoming year. Instead of stoking this fear in their hearts, Southerners could remain “patriots and good citizens’ by “behaving themselves” in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election. However, the Press and Tribune cynically mused that the “dissolution” of the Union would only be averted until the South had a “full crop.” Articles in partisan papers such as the Chicago Press and Tribune reveal the broad spectrum of fears endemic to the United States in the months leading up to the Election of 1860.

26

Jul

10

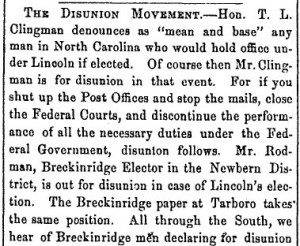

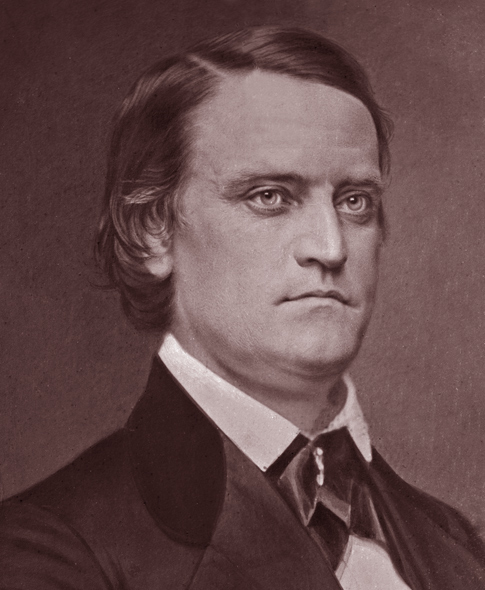

Election of 1860 – John Breckinridge

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Contests & Elections After southern Democratic delegates in Baltimore, Maryland refused to accept Senator Stephen Douglas as a candidate for the election of 1860, they nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge on June 23, 1860. Soon after Breckinridge’s campaign biography was published, which one can read online at archive.org. Some editors saw Breckinridge’s campaign and, in particular his supporters, as a serious threat to the Union. The Lowell (MA) Citizen & News, which supported the Republican party, warned that the group’s ultimate goal was secession. “There [were] many prominent southern supporters of Breckinridge and Lane who go for that ticket …[because it] will be most likely to achieve…a dissolution of the Union,” the Citizen & News argued. Southern newspapers like the Charlestown (VA) Free Press, which supported the Constitutional Union party, reached a similar conclusion. “No sane man can doubt that a dissolution of the Union is the ultimate object of the Seceders who put up Breckinridge and Lane as their leaders,” as the Free Press concluded. Editors who backed other candidates wanted Breckinridge to explain what actions he would recommend in the event of a Republican victory in November 1860. After a speech in Lexington, Kentucky, the Richmond (VA) Whig noted that “[Breckinridge] did not say, nor did he dare say, what course he would advise the Seceding and Disunion party…to take in case a Black Republican President” win the election. The (Jackson) Mississippian, however, used the same speech to reach the opposite conclusion. “It [was] a great speech, perfectly overwhelming in its refutation of the charges…of ‘disunion,’” as the Mississippian explained. (The full text of Breckinridge’s speech is available in an articled published on the New York Times’ website). Breckinridge, as the Mississippian argued, “had always been the able and faithful champion of ‘the Union, the Constitution, and the equality of the States.’” Breckinridge attempted to bridge the sectional divide after Lincoln’s victory in November 1860, but twelve months after the election he joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general.

After southern Democratic delegates in Baltimore, Maryland refused to accept Senator Stephen Douglas as a candidate for the election of 1860, they nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge on June 23, 1860. Soon after Breckinridge’s campaign biography was published, which one can read online at archive.org. Some editors saw Breckinridge’s campaign and, in particular his supporters, as a serious threat to the Union. The Lowell (MA) Citizen & News, which supported the Republican party, warned that the group’s ultimate goal was secession. “There [were] many prominent southern supporters of Breckinridge and Lane who go for that ticket …[because it] will be most likely to achieve…a dissolution of the Union,” the Citizen & News argued. Southern newspapers like the Charlestown (VA) Free Press, which supported the Constitutional Union party, reached a similar conclusion. “No sane man can doubt that a dissolution of the Union is the ultimate object of the Seceders who put up Breckinridge and Lane as their leaders,” as the Free Press concluded. Editors who backed other candidates wanted Breckinridge to explain what actions he would recommend in the event of a Republican victory in November 1860. After a speech in Lexington, Kentucky, the Richmond (VA) Whig noted that “[Breckinridge] did not say, nor did he dare say, what course he would advise the Seceding and Disunion party…to take in case a Black Republican President” win the election. The (Jackson) Mississippian, however, used the same speech to reach the opposite conclusion. “It [was] a great speech, perfectly overwhelming in its refutation of the charges…of ‘disunion,’” as the Mississippian explained. (The full text of Breckinridge’s speech is available in an articled published on the New York Times’ website). Breckinridge, as the Mississippian argued, “had always been the able and faithful champion of ‘the Union, the Constitution, and the equality of the States.’” Breckinridge attempted to bridge the sectional divide after Lincoln’s victory in November 1860, but twelve months after the election he joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general.

26

Jul

10

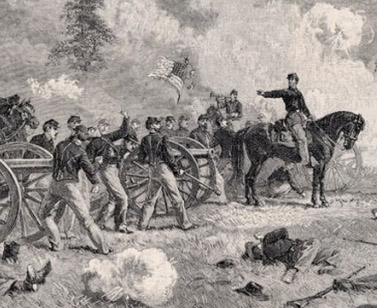

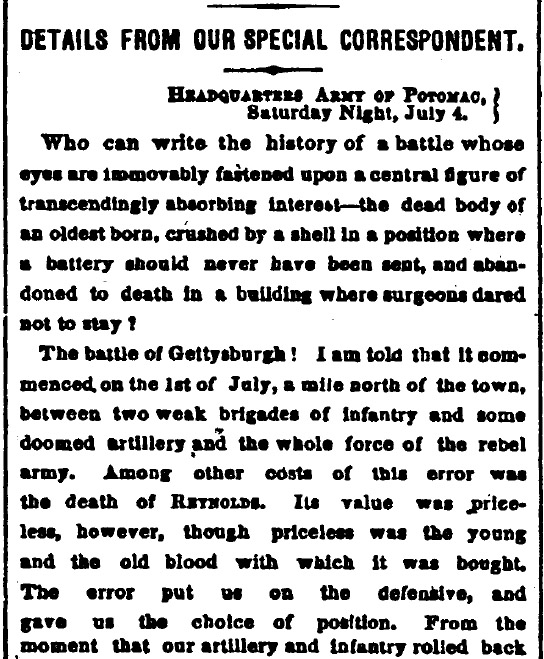

An Angry Father At Gettysburg

Posted by Matthew Pinsker Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals, Images Themes: Battles & Soldiers Sam Wilkeson was a war correspondent for the New York Times who had sons in the Union army, including Lt. Bayard Wilkeson, an artillery officer who was mortally wounded on the first day at Gettysburg. The story of Bayard’s death became a northern sensation since he was one of the youngest artillery officers in the army, the son of a prominent journalist and also because he died in a particularly heroic fashion. The young lieutenant covered the retreating forces from the Union XI Corps on the battle’s first day and reportedly had to amputate his own shattered leg when doctors were forced to flee in the face of the oncoming Confederates. The elder Wilkeson, who was married to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s sister, recovered his mangled son’s body in Gettysburg’s aftermath and wrote an angry report in the Times which appeared on July 6. The article began: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest –the dead body of an oldest born son, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay.” Unionists later redistributed the moving piece as a pamphlet under the title: Samuel Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture Of Gettysburgh. Artist Alfred Waud also drew a famous sketch of the young Wilkeson directing his battery on the battlefield. The story remains one of the most compelling of the battle. You can read more about it here at a special blog site built by Civil War enthusiast Randy Chadwick. Also, Louis M. Starr’s Bohemian Brigade: Civil War Newsmen in Action (1954) provides good context and more detail about Sam Wilkeson, one of the nation’s first embedded war correspondents. A more recent study by Michael A. Dreese, Torn Families: Death and Kinship at the Battle of Gettysburg (2007), provides several descriptive pages (available through Google Books) as part of a fascinating chapter on fathers and sons during the war.

Sam Wilkeson was a war correspondent for the New York Times who had sons in the Union army, including Lt. Bayard Wilkeson, an artillery officer who was mortally wounded on the first day at Gettysburg. The story of Bayard’s death became a northern sensation since he was one of the youngest artillery officers in the army, the son of a prominent journalist and also because he died in a particularly heroic fashion. The young lieutenant covered the retreating forces from the Union XI Corps on the battle’s first day and reportedly had to amputate his own shattered leg when doctors were forced to flee in the face of the oncoming Confederates. The elder Wilkeson, who was married to Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s sister, recovered his mangled son’s body in Gettysburg’s aftermath and wrote an angry report in the Times which appeared on July 6. The article began: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest –the dead body of an oldest born son, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay.” Unionists later redistributed the moving piece as a pamphlet under the title: Samuel Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture Of Gettysburgh. Artist Alfred Waud also drew a famous sketch of the young Wilkeson directing his battery on the battlefield. The story remains one of the most compelling of the battle. You can read more about it here at a special blog site built by Civil War enthusiast Randy Chadwick. Also, Louis M. Starr’s Bohemian Brigade: Civil War Newsmen in Action (1954) provides good context and more detail about Sam Wilkeson, one of the nation’s first embedded war correspondents. A more recent study by Michael A. Dreese, Torn Families: Death and Kinship at the Battle of Gettysburg (2007), provides several descriptive pages (available through Google Books) as part of a fascinating chapter on fathers and sons during the war.

To view a slideshow in Flickr, click on any of the images below:

24

Jul

10

The Courtship of James Garfield

Posted by hardyr Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Education & Culture, Women & Families In 1847, Zeb and Arabella Rudolph decided that their daughter Lucretia needed more of an academic challenge than the local Garrettsville, Ohio, schools could offer. The fifteen-year old was sent twenty miles away to board at the Geauga Seminary, where she would have the benefit of a classical curriculum. The Geauga Seminary was coeducational, and one of Lucretia’s fellow pupils there was an awkward and earnest sixteen-year old boy named James Garfield.

In 1847, Zeb and Arabella Rudolph decided that their daughter Lucretia needed more of an academic challenge than the local Garrettsville, Ohio, schools could offer. The fifteen-year old was sent twenty miles away to board at the Geauga Seminary, where she would have the benefit of a classical curriculum. The Geauga Seminary was coeducational, and one of Lucretia’s fellow pupils there was an awkward and earnest sixteen-year old boy named James Garfield.

“A prodigy,” Lucretia called him.

In 1850, Lucretia left the Geauga Seminary and enrolled in the new Hiram Eclectic Institute in Hiram, Ohio. The following year, Garfield also enrolled at Hiram, and Lucretia experienced the unexpected thrill of meeting “a pair of eyes…as once I looked up from a hard sentence somewhere in the fore part of the Greek grammar.” It wasn’t exactly love at first conjugation—both she and James were recovering from painful break-ups—but in 1853 James surprised Lucretia with a letter written during an excursion to Niagara Falls, and soon the two were engaged in a full-fledged correspondence.

At first, they addressed each other as Brother and Sister. They wrote about the books they were reading, and about their shared enthusiasm for teaching. James was teaching Latin and Greek at Hiram, and Lucretia was teaching at a public school in Chagrin Falls, and attempting to keep pace with James’s Latin class in reading Virgil.

“I would like to know how many hundred lines the Virgil class are ahead of me,” she wrote to James in November 1853.

“Today, the Virgil class finished the third book and are going about 50 lines per day,” Jame wrote back on December 8. “Are you ahead? I presume so. Won’t you come in to both Greek and Latin in the spring? We miss you very much in these two classes. What are your views with regard to studying the classics? Have you reconciled yourself to devoting a few more years to them? I would like to hear your reasonings on the subject.”

Replying six days later, Lucretia confessed that she had laid aside Virgil for the winter. As to the study of classics in general, she wrote: “Candidly, I will confess that thus far I have prosecuted the study of them without any argument in their favor which appeared to me conclusive.” She admitted that the study of Greek and Latin provided “rigid mental discipline,” but she wondered if there might be other means of acquiring that discipline.

“I wish you would convince me of their superior merit if they really possess it,” she wrote; “for I do not like to give them up—neither do I like to continue in them feeling that precious moments are being wasted…”

This discussion continued in several letters over the following months. Meanwhile, James quietly dropped the pretense of calling her Sister, and soon Lucretia was sending James her “warmest love.” In March 1854, the subject of marriage was raised.

James A. Garfield—veteran of Shiloh and Chickamauga, Union general, and twentieth President of the United States—courted his wife with a debate over the value of a classical education.

The correspondence of James and Lucretia Garfield can be found in John Shaw, ed. Crete and James: Personal Letters of Lucretia and James Garfield (Michigan State University Press 1994). For a biography of Lucretia Garfield, see John Shaw, Lucretia (Nova History Publications, 2001). On James Garfield’s study of the classics, see Susan Ford Wiltshire’s essay, “The Classicist President” (.pdf).

23

Jul

10

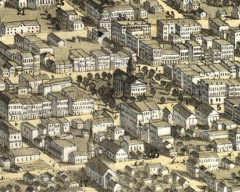

Election Day in Springfield, Illinois

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Maps “The Cannon Salvo that thundered over Springfield, Illinois, to greet the sunrise on November 6, 1860, signaled not the start of a battle, but the end of one…Election Day was finally dawning.” – Historian Harold Holzer

“The Cannon Salvo that thundered over Springfield, Illinois, to greet the sunrise on November 6, 1860, signaled not the start of a battle, but the end of one…Election Day was finally dawning.” – Historian Harold Holzer

Abraham Lincoln, however, was not one to rush and vote right after the polling places opened in the morning. He apparently waited until 3:30pm when, as the New York Tribune explained, “the multitude…[had] diminished sufficiently to allow tolerably free passage.” The Tribune’s correspondent described what happened once the crowd realized that Lincoln had arrived:

“at that moment he was suddenly saluted with the wildest outbursts of enthusiasm every yielded by a popular assemblage. All party feelings seemed to be forgotten and even the distributors of opposition tickets joined in the overwhelming demonstrations of greeting…there was only one sentiment expressed – that of the heartiest and most undivided delight at his appearance. Mr. Lincoln advanced as rapidly as possible to the voting table and handed in his ticket, upon which, it is hardly necessary to say, all the names were sound republicans. The only alteration he made was the cutting off of his own name from the top where it had been printed.”

As Holzer explains, “Lincoln modestly cut his own name..from his ticket” and “vot[ed] only for his party’s candidates for state and local office.” Later that evening Lincoln went to the local telegraph office, where he waited for reports on election returns from across the country. “All safe in this state,” as Thurlow Weed explained from Albany, New York. Simon Cameron sent word from Philadelphia, Pennsylvanian, while a report from Alton, Illinois, noted that “[Republicans] have checkmated [Democrats’] scheme of fraud.” “Those who saw [Lincoln] at the time,” as the New York Times observed, “say it would have been impossible for a bystander to tell that that tall, lean, wiry, good-natured, easy-going gentleman…was the choice of the people to fill the most important office in the nation.”

22

Jul

10

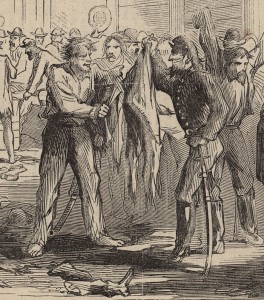

Harrisburg Grand Review: November 14, 1865

Posted by rainwatj Published in Civil War (1861-1865), Historic Periodicals Themes: Battles & Soldiers On May 23 and 24, 1865, Union soldiers paraded through Washington D.C. for a grand review of the troops, a celebration from the grateful citizens to the Union soldiers for their efforts and service in winning the Civil War. Noticeably missing from the celebration were the over 180,000 United States Colored Troops who fought along side these troops being honored in the nation’s capital. While denied participation in the “Grand Review of the Armies,” black regiments from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts gathered in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on November 14, 1865 for their own Grand Review. Thomas Morris Chester, a prominent Harrisburg resident and recruiter of black soldiers served as grand marshal of the Grand Review. The troops marched through the main streets of the Pennsylvania capital to the home of Senator Simon Cameron who delivered a speech honoring the black troops and commending them for their service and sacrifice to the Union. Cameron, an abolitionist and one of the early advocates for using black troops in the war, gratefully acknowledged the soldiers in the speech that was reprinted in the North American and United States Gazette in Philadelphia the following day.

On May 23 and 24, 1865, Union soldiers paraded through Washington D.C. for a grand review of the troops, a celebration from the grateful citizens to the Union soldiers for their efforts and service in winning the Civil War. Noticeably missing from the celebration were the over 180,000 United States Colored Troops who fought along side these troops being honored in the nation’s capital. While denied participation in the “Grand Review of the Armies,” black regiments from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts gathered in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on November 14, 1865 for their own Grand Review. Thomas Morris Chester, a prominent Harrisburg resident and recruiter of black soldiers served as grand marshal of the Grand Review. The troops marched through the main streets of the Pennsylvania capital to the home of Senator Simon Cameron who delivered a speech honoring the black troops and commending them for their service and sacrifice to the Union. Cameron, an abolitionist and one of the early advocates for using black troops in the war, gratefully acknowledged the soldiers in the speech that was reprinted in the North American and United States Gazette in Philadelphia the following day.

“I cannot let this opportunity pass without thanking the African soldiers for the compliment they have paid me, but more than all to thank them for the great service which they have been to their country in the terrible rebellion. Like all other men, you have your destinies in your own hands, and if you continue to conduct yourselves hereafter as you have in the struggle, you will have all the rights you ask for, all the rights that belong to human beings.”

The report called the celebration a success throughout and estimated that nearly seven thousand blacks attended the Grand Review as well as a sizable white population who came to pay their respects to “those who escaped the perils of a contest in which they risked their lives in defense of the nation honor and support of the constitutional authorities.” One of the prominent black participants was Reverend John Walker Jackson who offered a prayer that served as “a beautiful acknowledgment of the services which the black man rendered in the struggle for American nationality, civilization and freedom. The orator of the event, William Howard Day, discussed the attitude of the colored man and “the prospect which lay before him for improvement, social elevation and the acquirement of political rights.” The Grand Review concluded with a grand ball where the soldiers and those honoring them convened one last time.

21

Jul

10

Southern Reaction to the Republican National Convention

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Contests & Elections After the Republican National Convention selected Abraham Lincoln in May 1860 as their candidate for the 1860 election, some Republican newspaper editors noted that Lincoln was a moderate politician. Lincoln opposed the further extension of slave territory, but he did not call for the end of slavery in the South. Yet some southern editors were quick to characterize him as a dangerous radical who would destroy slavery and the Union. The Fayetteville (NC) Observer, which supported the Constitutional Union party, called Lincoln an “ultra abolitionist.” Republicans “[had]… selected [him] to split the Union,” as the Democratic Charleston (SC) Courier explained. Other editors focused on the threat from the Republican party’s “objects” rather than a specific candidate. The (Jackson) Mississippian, a Democratic paper, observed that the “Black Republican’s” overall objective “[was] to degrade the southern States from their positions of equality in the Union and to destroy their social and political institutions.” One might assume that these editors would support secession after Lincoln’s victory. While that was true for the Charleston (SC) Courier and the The (Jackson) Mississippian, the Fayetteville (NC) Observer supported unionists until President Lincoln called for volunteers after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861.

After the Republican National Convention selected Abraham Lincoln in May 1860 as their candidate for the 1860 election, some Republican newspaper editors noted that Lincoln was a moderate politician. Lincoln opposed the further extension of slave territory, but he did not call for the end of slavery in the South. Yet some southern editors were quick to characterize him as a dangerous radical who would destroy slavery and the Union. The Fayetteville (NC) Observer, which supported the Constitutional Union party, called Lincoln an “ultra abolitionist.” Republicans “[had]… selected [him] to split the Union,” as the Democratic Charleston (SC) Courier explained. Other editors focused on the threat from the Republican party’s “objects” rather than a specific candidate. The (Jackson) Mississippian, a Democratic paper, observed that the “Black Republican’s” overall objective “[was] to degrade the southern States from their positions of equality in the Union and to destroy their social and political institutions.” One might assume that these editors would support secession after Lincoln’s victory. While that was true for the Charleston (SC) Courier and the The (Jackson) Mississippian, the Fayetteville (NC) Observer supported unionists until President Lincoln called for volunteers after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861.

20

Jul

10

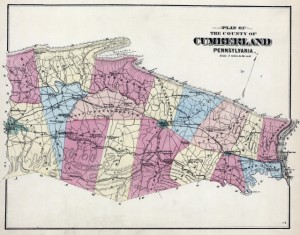

Cumberland County History, a historical journal compiled annually by the Cumberland County Historical Society, has provided nearly three decades of research into the county’s long history. The journal has published several articles on Civil War soldiers from the surrounding community. They utilize several primary documents and effectively offer insight into the emotional departure from loved ones, the lives of soldiers during the war, and the enemy just beyond the Mason-Dixon Line.

Cumberland County History, a historical journal compiled annually by the Cumberland County Historical Society, has provided nearly three decades of research into the county’s long history. The journal has published several articles on Civil War soldiers from the surrounding community. They utilize several primary documents and effectively offer insight into the emotional departure from loved ones, the lives of soldiers during the war, and the enemy just beyond the Mason-Dixon Line.

James A. Holechek features the Civil War experiences of John Cantilion in his article “From Carlisle and Fort Couch: The War of Corporal John A. Cantilion.” By tracing his service in the United States army through to his untimely death in November 1863, Holechek surmises the emotions inherent to leaving loved ones behind as a soldier and, conversely, watching a loved one leave to fight in battle. Letters became the only connection between Cantilion and his wife and children. Accordingly, Holechek used these letters as a window into how the separation affected both parties.

The letters of Lt. Thomas William Sweeny are discussed and provided in part in “Carlisle Barracks –1854-1855: From the Letters of Lt. Thomas W. Sweeny, 2nd Infantry,” edited by Robert Coyer. Sweeny stayed in the Carlisle Barracks for some time during the 1850s before moving to Missouri as a general recruiter for the Union. His time spent in Missouri, as argued by Coyer, “played a major part in keeping the state from seceding.” Most of Coyer’s article centers around several letters he wrote to his wife through 1854 and 1855, part of the time he spent at the Barracks. Though these letters could not note the anguish of separation of loved ones during the war, the tense and difficult relations between the couple become apparent when reading even the first letter.

Patricia M. Coolmeyer collects the perspectives of Civil War soldiers from southern Pennsylvania through the extensive use of personal letters, diaries, and local newspapers. Her article, “Southern Sentiments: A Look at Attitudes of Civil War Soldiers,” illustrates the ways Carlisle, given its geographic proximity to the Mason-Dixon Line, often exchanged its culture and relations with the South. As a result, towns like Carlisle did not uniformly despise the South but rather saw an “active pro-Southern element.” This lack of uniformity emerged in Pennsylvanian soldiers. From one perspective, Union soldiers saw Southerners as “quite a fine looking, gentlemanly set of fellows. Others shaped their perceptions based on the beautiful landscape of the South. Each soldier found different ways to build their allegiance to the Union, but, as Coolmeyer makes clear, it did not always emerge out of a hatred of the South.

The Cumberland County Historical Society has granted us special permission to publish these articles. We encourage readers to utilize their resources, for they have compiled an extensive library filled with primary documents and modern scholarly research. Please consult their website for more information including how to contact the Society.