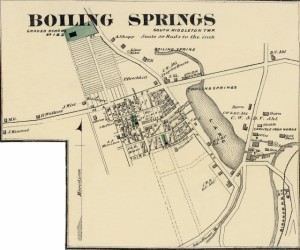

Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania embraced the transportation and protection of fugitive slaves moving northward across the Mason-Dixon Line. Daniel Kaufman (alternately spelled Kauffman), born in Cumberland County in 1818, laid out designs for the town and helped make his presence known. His support for the Underground Railroad strengthened in Boiling Springs, as indicated by the events of October 24, 1847.

Boiling Springs, Pennsylvania embraced the transportation and protection of fugitive slaves moving northward across the Mason-Dixon Line. Daniel Kaufman (alternately spelled Kauffman), born in Cumberland County in 1818, laid out designs for the town and helped make his presence known. His support for the Underground Railroad strengthened in Boiling Springs, as indicated by the events of October 24, 1847.

As shown by evidence later presented in court, thirteen slaves belonging to the Oliver family escaped in Maryland, crossed the border into Pennsylvania, and eventually found themselves in Kaufman’s barn in Boiling Springs. Kaufman consented to provide them with shelter and food, and within the next day he offered up his wagon to transport the slaves across the Susquehanna River. News of the fugitive slaves spread, and within a few short months the slave owner’s family filed a lawsuit against Kaufman.

The Court of Common Pleas of Cumberland County opened the case Oliver et al. v. Kaufman against Kaufman and two other known associates, Stephen Weakley and Philip Breckbill. The defendants argued that the suit could not be tried in state court as the issue pertained to federal law. Nevertheless, the jury delivered a verdict in favor of the plaintiff; Kaufman had to pay $2000 in damages. When a panel of judges of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court oversaw the case, their “majority opinion” notably argued “that Congress possesses the exclusive right to legislate on the subject [of fugitive slaves] and that State Legislatures have no right whatever” and could therefore not recover any damages. The Cumberland County Court’s ruling was reversed. The case continued in 1852, this time in a federal court, only to conclude in favor of the plaintiff and with Kaufman liable to approximately $4000 in damages and fines.

Kaufman’s case occurred during a period of heavy debate in Pennsylvania regarding state sovereignty and the adherence to federal mandates including the Fugitive Slave Laws of 1793 and 1850. Prior to the case seen in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania judges gave credence to the state’s “common law” and “clear right to declare that a slave brought within her territory becomes ipso facto a freeman,” as quoted by a law journal in Paul Finkleman’s An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity. traced the evolution of state sovereignty in Pennsylvania.

For a more detailed summary of the cases, the House Divided record of the case provides access to several primary documents, including newspaper articles and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision to reverse the ruling of the case. Finkleman’s book puts Kaufman’s trial into context, but his summary of the case will help those even vaguely familiar with its nuances. LexisNexis, though requiring a subscription, grants access not only to the court documents, but to modern scholarship on the case’s wider importance in the debate on Federalism and state’s rights. In Robert Kaczorowski’s article “Federalism in the 21ST Century,” the Fugitive Slave Laws emerge as the focal point for a much wider debate on the intent of the Founding Fathers with regard to state rights and federal mandates.