When Democrats held a rally in Carlisle, Pennsylvania on October 6, 1860, the Carlisle (PA) American Volunteer reported that no one had been ready for the “overwhelming avalanche” of delegates from “every town and township in the county.” Over 8,000 people filled the streets before noon, according to some estimates. The American Volunteer backed Senator Stephen Douglas and supported this event as a means to rally Democratic voters before a critical election. In the months before the election, the American Volunteer tried to convince Cumberland County residents that the Republican party represented a serious threat. “The election of LINCOLN will be the death-knell to our Republic,” as the American Volunteer warned. As Republican “Wide Awake” groups held parades in northern cities, the American Volunteer reported that “each man carried a six-barreled revolver” in order to demonstrate that “LINCOLN and his party are determined to carry out their sectional doctrines at all hazards and at any sacrifice.” The American Volunteer saw Republicans as a “sectional Abolition party” which was determined to “humble the South [and] root out slavery.” If Republicans carried out their plan, the American Volunteer predicted that “every State in the Union will be bathed in blood.” Only a Democratic victory in November 1860 would ensure a future for the Union. If Lincoln won, the American Volunteer observed that it “will be regarded as a declaration of war.” Yet the American Volunteer’s arguments failed to convince a sufficient number of Cumberland County voters – Lincoln ended up with a 400 vote majority. “A long dreary winter is ahead,” the American Volunteer predicted.

3

Nov

10

Election of 1860 – Carlisle American Volunteer

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Carlisle & Dickinson, Contests & Elections27

Oct

10

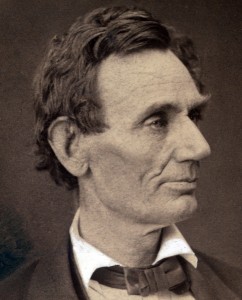

As the 150th anniversary of the 1860 election is next week, the House Divided project has just published seven interactive essays at Journal Divided that focus on different aspects of Abraham Lincoln’s campaign. These essays have been adapted with permission from the unedited manuscript of Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008). One can read about the origins of the “rail-splitter” image and Lincoln’s efforts to gain support from the Know Nothings. In addition, one will find an overview of the Republican National Convention as well as a detailed look at how Lincoln won the nomination. While Lincoln instructed his allies at the convention to “make no contracts that will bind me,” Burlingame discusses the contradictory claims and evidence about the deals made to secure Lincoln’s nomination. In the final essay Burlingame examines the political conditions that produced a Republican victory in November 1860. As you read the essays, be sure to click through the sidenotes on every page. These contain links to relevant records on House Divided, including those for documents, events, people, place, major topics, and sources. For example, the Gott resolution is mentioned on page 5 of the “Lincoln Know Nothing” essay. If you are unfamiliar with that topic, simply click on the “Events” sidenote to learn more. Each essay also has a video, which you can watch by clicking on the YouTube icon.

28

Sep

10

Election of 1860 – “Mr. Lincoln A Black Man”

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic PeriodicalsWhen European newspapers discussed Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the Election of 1860, their reporters did not always provide the correct details. In January 1861 the (Montpelier) Vermont Patriot highlighted a mistake in an editorial from the Drogheda (Ireland) Argus, which discussed the implications of “a black Man’s” victory for the United States. “No Presidential election has excited so much party feelings as has the election of Abraham Lincoln, a black gentleman,” as the Argus noted. The paper also claimed that Lincoln had been “unknown out of [Illinois]” before the 1860 election. While he might have been “unknown as a public man in Europe,” Lincoln had emerged as a national political figure during the Lincoln Douglas debates in 1858. After returning home to New York in July 1858, Charles H. Ray described how those outside Illinois were interested in Lincoln and the campaign:

“In my journey here from Chicago, and even here [in Norwich, New York]– one of the most out-of-the-way, rural districts in the State, among a slow-going and conservative people, who are further from railroads than any man can be in Illinois — I have found hundreds of anxious enquirers burning to know all about the newly raised-up opponent of Douglas… In fact, you have sprung at once from the position of a “capital fellow” and a “leading lawyer” in Illinois, to the enjoyment of a national reputation. Your speeches are read with great avidity by all political men…”

You can read more about Lincoln and his political career in Edwin Erie Sparks’ The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858 (1908), David Donald’s Lincoln (1995), and Allen C. Guelzo’s Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America (2008).

24

Sep

10

Election of 1860 – Ulysses S. Grant

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images, Letters & Diaries Themes: Contests & Elections The Ulysses S. Grant Association at Mississippi State University has digitized all 31 volumes included in the Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. This project also offers a chronology and a nice collection of images. In August 1860 Grant observed that “the Democratic party want a little purifying and nothing will do it so effectually as a defeat.” However, Grant did not want Abraham Lincoln to win in November 1860. “The only thing is dont like to see a Republican beat the [Democratic] party,” as Grant explained. After Lincoln won the election, Grant could not believe that southern Democrats would accept secession. “It is hard to realize that a State or States should commit so suicidal an act as to secede from the Union,” as Grant noted. You can learn more about Grant’s career in William S. McFeely’s Grant: A Biography (1981) and Jean Edward Smith’s Grant (2001). Brooks Simpson focuses on Grant’s role during the Civil War and Reconstruction in Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861-1868 (1991).

The Ulysses S. Grant Association at Mississippi State University has digitized all 31 volumes included in the Papers of Ulysses S. Grant. This project also offers a chronology and a nice collection of images. In August 1860 Grant observed that “the Democratic party want a little purifying and nothing will do it so effectually as a defeat.” However, Grant did not want Abraham Lincoln to win in November 1860. “The only thing is dont like to see a Republican beat the [Democratic] party,” as Grant explained. After Lincoln won the election, Grant could not believe that southern Democrats would accept secession. “It is hard to realize that a State or States should commit so suicidal an act as to secede from the Union,” as Grant noted. You can learn more about Grant’s career in William S. McFeely’s Grant: A Biography (1981) and Jean Edward Smith’s Grant (2001). Brooks Simpson focuses on Grant’s role during the Civil War and Reconstruction in Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861-1868 (1991).

30

Aug

10

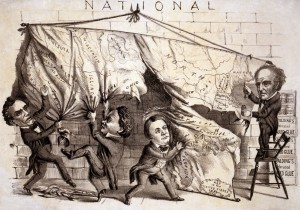

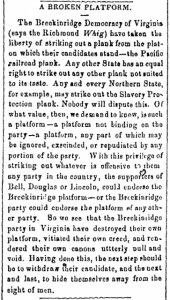

The Complicated Partisan Realities of 1860

Posted by Matthew Pinsker Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Contests & Elections One hundred and fifty years ago today, the Charles Town, Virgina (there wasn’t a West Virginia yet)Free Press commented on reports that the state’s Breckinridge Democrats had abandoned a plank from their “national” party platform by repudiating support for the Pacific Railroad. This one little piece of fewer than 200 words illustrates how complicated the 1860 election was and how challenging it is for students to read nineteenth-century newspapers. The Free Press was a loyal southern rights Democratic paper run by the Gallaher family. They supported John Breckinridge, the nominee of the Southern Democrats and his new party’s attempts to cultivate western support through actions such as endorsing the Pacific (or transcontinental) Railroad and by anointing Senator Joseph Lane from Oregon as the party’s vice-presidential nominee. Yet the article, entitled “A Broken Platform,” reads like harsh criticism of the decision. “So we see,” reads the piece, “that the Breckinridge party in Virginia have destroyed their own platform, vitiated their own creed, and rendered their own canons null and void.” However, a careful reader will note that the piece begins with a parenthetical aside “(says the Richmond Whig)” referring to a leading paper in the state capital that supported John Bell and the Constitutional Union Party. Supporters of Breckinridge and Bell vied fiercely across southern states during the 1860 contest and by quoting from the Richmond Whig the Virginia Free Press was being sarcastic. Nineteenth-century readers understood the nuances (or so we imagine) but the finer differences and unique customs of partisan journalism are very difficult to explain to modern-day students.

One hundred and fifty years ago today, the Charles Town, Virgina (there wasn’t a West Virginia yet)Free Press commented on reports that the state’s Breckinridge Democrats had abandoned a plank from their “national” party platform by repudiating support for the Pacific Railroad. This one little piece of fewer than 200 words illustrates how complicated the 1860 election was and how challenging it is for students to read nineteenth-century newspapers. The Free Press was a loyal southern rights Democratic paper run by the Gallaher family. They supported John Breckinridge, the nominee of the Southern Democrats and his new party’s attempts to cultivate western support through actions such as endorsing the Pacific (or transcontinental) Railroad and by anointing Senator Joseph Lane from Oregon as the party’s vice-presidential nominee. Yet the article, entitled “A Broken Platform,” reads like harsh criticism of the decision. “So we see,” reads the piece, “that the Breckinridge party in Virginia have destroyed their own platform, vitiated their own creed, and rendered their own canons null and void.” However, a careful reader will note that the piece begins with a parenthetical aside “(says the Richmond Whig)” referring to a leading paper in the state capital that supported John Bell and the Constitutional Union Party. Supporters of Breckinridge and Bell vied fiercely across southern states during the 1860 contest and by quoting from the Richmond Whig the Virginia Free Press was being sarcastic. Nineteenth-century readers understood the nuances (or so we imagine) but the finer differences and unique customs of partisan journalism are very difficult to explain to modern-day students.

16

Aug

10

Election of 1860 – Hinton Rowan Helper

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Rare Books Themes: Contests & Elections Even though Hinton Rowan Helper published The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It in 1857, the book was still a factor in the election of 1860. While Helper was born in North Carolina to a family that owned more than 200 slaves, he used the Impending Crisis to call for the South to end slavery. That institution, as Helper argued, limited the economic potential of white labor and prevented the South’s economy from developing. In 1859 Helper published the Compendium of the Impending Crisis of the South – a cheaper edition of that reached thousands of readers. By the election of 1860 northern Democratic editors like James Gordon Bennett, who owned the New York Herald, used Helper’s book as evidence that the Republican party was dangerous to the United States. On election day in November 1860 the Herald warned voters that Republicans had “circulated hundreds of thousands of Helper’s handbook of treason.” Prominent Republicans had endorsed the book, which as the Herald explained, were “[distributed] to abolitionize the Northern mind.” If Abraham Lincoln became President, the Herald argued that “one phase of [his] administration [would be] to engender or to inaugurate, if possible, a civil war at the South between the non-slaveholding whites of that section (excited by abolition emissaries) and those who own slaves.” One of the best secondary sources on Helper is David Brown’s Southern Outcast: Hinton Rowan Helper and The Impending Crisis of the South (2006).

Even though Hinton Rowan Helper published The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It in 1857, the book was still a factor in the election of 1860. While Helper was born in North Carolina to a family that owned more than 200 slaves, he used the Impending Crisis to call for the South to end slavery. That institution, as Helper argued, limited the economic potential of white labor and prevented the South’s economy from developing. In 1859 Helper published the Compendium of the Impending Crisis of the South – a cheaper edition of that reached thousands of readers. By the election of 1860 northern Democratic editors like James Gordon Bennett, who owned the New York Herald, used Helper’s book as evidence that the Republican party was dangerous to the United States. On election day in November 1860 the Herald warned voters that Republicans had “circulated hundreds of thousands of Helper’s handbook of treason.” Prominent Republicans had endorsed the book, which as the Herald explained, were “[distributed] to abolitionize the Northern mind.” If Abraham Lincoln became President, the Herald argued that “one phase of [his] administration [would be] to engender or to inaugurate, if possible, a civil war at the South between the non-slaveholding whites of that section (excited by abolition emissaries) and those who own slaves.” One of the best secondary sources on Helper is David Brown’s Southern Outcast: Hinton Rowan Helper and The Impending Crisis of the South (2006).

28

Jul

10

Election of 1860 – Southerners Unionists

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Contests & Elections While some southern editors argued before election day in November 1860 that a Republican victory would justify secession, the Fayetteville (NC) Observer was prepared to accept Abraham Lincoln as President. The Observer, which supported Constitutional Union candidates John Bell and Edward Everett, believed that there was no choice but to accept the results of an election that they participated in. If “[it was] decided constitutionally,” the Observer explainedthat “we [were] honor bound to abide its results.” Southerners who threatened to secede only created more problems, particularly those who were not prepared to follow through with their threats. “We have had enough of ultimatum-manufacturing,” as the Observer noted. Those southerners had a bad “habit of invariably back out after” issuing ultimatums and, as the Observer argued, the repeated false alarms “[had] made the North believe that the South cannot be kicked out of the Union.” This scenario was dangerous since the Observer, like other unionist papers, did not completely reject secession as an option. If President Lincoln took any action that they considered a threat to slavery, many would support disunion. For the Observer and other ‘conditional’ unionists, the turning point was President Lincoln’s call for volunteers after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861. One of the best sources on southern unionists’ perspectives during this period is Daniel W. Crofts’ Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (1989). While Crofts discusses the Upper South, Edward Ayers focuses on southern unionists Augusta County, Virginia in In the Presence of Mine Enemies: War in the Heart of America, 1859-1863 (2003). You can learn more about that community online at the Valley of the Shadow project.

While some southern editors argued before election day in November 1860 that a Republican victory would justify secession, the Fayetteville (NC) Observer was prepared to accept Abraham Lincoln as President. The Observer, which supported Constitutional Union candidates John Bell and Edward Everett, believed that there was no choice but to accept the results of an election that they participated in. If “[it was] decided constitutionally,” the Observer explainedthat “we [were] honor bound to abide its results.” Southerners who threatened to secede only created more problems, particularly those who were not prepared to follow through with their threats. “We have had enough of ultimatum-manufacturing,” as the Observer noted. Those southerners had a bad “habit of invariably back out after” issuing ultimatums and, as the Observer argued, the repeated false alarms “[had] made the North believe that the South cannot be kicked out of the Union.” This scenario was dangerous since the Observer, like other unionist papers, did not completely reject secession as an option. If President Lincoln took any action that they considered a threat to slavery, many would support disunion. For the Observer and other ‘conditional’ unionists, the turning point was President Lincoln’s call for volunteers after Confederates attacked Fort Sumter in April 1861. One of the best sources on southern unionists’ perspectives during this period is Daniel W. Crofts’ Reluctant Confederates: Upper South Unionists in the Secession Crisis (1989). While Crofts discusses the Upper South, Edward Ayers focuses on southern unionists Augusta County, Virginia in In the Presence of Mine Enemies: War in the Heart of America, 1859-1863 (2003). You can learn more about that community online at the Valley of the Shadow project.

28

Jul

10

Partisan Fear-mongering in 1860

Posted by Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Images After what could only be mildly described as a tumultuous decade of failed compromises, the rise of a new political party, and a disgruntled citizenry, the 1860 Election season met with the pronounced fears over the future course of the United States. Partisan newspapers relished the opportunity to hack away at their opponents by castigating their political views and theorizing on pressing social fears within the South. The Chicago Press and Tribune noted that the “slave breeders” of the South feared a Republican party in their midst that could claim Founders as part of its political pedigree. The article also cites an undated piece from the New Orleans Courier which speculated that if Republicans proved victorious in the upcoming election, Southerners would have to openly embrace the patronage positions offered them as members of a new Southern Republican “nucleus.” (Ironically, Lincoln and his cabinet maintained their hope in a latent Southern Unionism in Virginia that would dissuade the Upper South from seceding.) Other fears for the upcoming election literally struck at the belly of the South. Again, the Chicago Press and Tribune stated that a “poor corn-crop” would precede a potential famine in the upcoming year. Instead of stoking this fear in their hearts, Southerners could remain “patriots and good citizens’ by “behaving themselves” in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election. However, the Press and Tribune cynically mused that the “dissolution” of the Union would only be averted until the South had a “full crop.” Articles in partisan papers such as the Chicago Press and Tribune reveal the broad spectrum of fears endemic to the United States in the months leading up to the Election of 1860.

After what could only be mildly described as a tumultuous decade of failed compromises, the rise of a new political party, and a disgruntled citizenry, the 1860 Election season met with the pronounced fears over the future course of the United States. Partisan newspapers relished the opportunity to hack away at their opponents by castigating their political views and theorizing on pressing social fears within the South. The Chicago Press and Tribune noted that the “slave breeders” of the South feared a Republican party in their midst that could claim Founders as part of its political pedigree. The article also cites an undated piece from the New Orleans Courier which speculated that if Republicans proved victorious in the upcoming election, Southerners would have to openly embrace the patronage positions offered them as members of a new Southern Republican “nucleus.” (Ironically, Lincoln and his cabinet maintained their hope in a latent Southern Unionism in Virginia that would dissuade the Upper South from seceding.) Other fears for the upcoming election literally struck at the belly of the South. Again, the Chicago Press and Tribune stated that a “poor corn-crop” would precede a potential famine in the upcoming year. Instead of stoking this fear in their hearts, Southerners could remain “patriots and good citizens’ by “behaving themselves” in the wake of Abraham Lincoln’s election. However, the Press and Tribune cynically mused that the “dissolution” of the Union would only be averted until the South had a “full crop.” Articles in partisan papers such as the Chicago Press and Tribune reveal the broad spectrum of fears endemic to the United States in the months leading up to the Election of 1860.

26

Jul

10

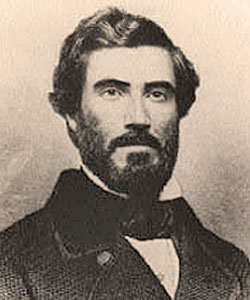

Election of 1860 – John Breckinridge

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals Themes: Contests & Elections After southern Democratic delegates in Baltimore, Maryland refused to accept Senator Stephen Douglas as a candidate for the election of 1860, they nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge on June 23, 1860. Soon after Breckinridge’s campaign biography was published, which one can read online at archive.org. Some editors saw Breckinridge’s campaign and, in particular his supporters, as a serious threat to the Union. The Lowell (MA) Citizen & News, which supported the Republican party, warned that the group’s ultimate goal was secession. “There [were] many prominent southern supporters of Breckinridge and Lane who go for that ticket …[because it] will be most likely to achieve…a dissolution of the Union,” the Citizen & News argued. Southern newspapers like the Charlestown (VA) Free Press, which supported the Constitutional Union party, reached a similar conclusion. “No sane man can doubt that a dissolution of the Union is the ultimate object of the Seceders who put up Breckinridge and Lane as their leaders,” as the Free Press concluded. Editors who backed other candidates wanted Breckinridge to explain what actions he would recommend in the event of a Republican victory in November 1860. After a speech in Lexington, Kentucky, the Richmond (VA) Whig noted that “[Breckinridge] did not say, nor did he dare say, what course he would advise the Seceding and Disunion party…to take in case a Black Republican President” win the election. The (Jackson) Mississippian, however, used the same speech to reach the opposite conclusion. “It [was] a great speech, perfectly overwhelming in its refutation of the charges…of ‘disunion,’” as the Mississippian explained. (The full text of Breckinridge’s speech is available in an articled published on the New York Times’ website). Breckinridge, as the Mississippian argued, “had always been the able and faithful champion of ‘the Union, the Constitution, and the equality of the States.’” Breckinridge attempted to bridge the sectional divide after Lincoln’s victory in November 1860, but twelve months after the election he joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general.

After southern Democratic delegates in Baltimore, Maryland refused to accept Senator Stephen Douglas as a candidate for the election of 1860, they nominated Vice President John C. Breckinridge on June 23, 1860. Soon after Breckinridge’s campaign biography was published, which one can read online at archive.org. Some editors saw Breckinridge’s campaign and, in particular his supporters, as a serious threat to the Union. The Lowell (MA) Citizen & News, which supported the Republican party, warned that the group’s ultimate goal was secession. “There [were] many prominent southern supporters of Breckinridge and Lane who go for that ticket …[because it] will be most likely to achieve…a dissolution of the Union,” the Citizen & News argued. Southern newspapers like the Charlestown (VA) Free Press, which supported the Constitutional Union party, reached a similar conclusion. “No sane man can doubt that a dissolution of the Union is the ultimate object of the Seceders who put up Breckinridge and Lane as their leaders,” as the Free Press concluded. Editors who backed other candidates wanted Breckinridge to explain what actions he would recommend in the event of a Republican victory in November 1860. After a speech in Lexington, Kentucky, the Richmond (VA) Whig noted that “[Breckinridge] did not say, nor did he dare say, what course he would advise the Seceding and Disunion party…to take in case a Black Republican President” win the election. The (Jackson) Mississippian, however, used the same speech to reach the opposite conclusion. “It [was] a great speech, perfectly overwhelming in its refutation of the charges…of ‘disunion,’” as the Mississippian explained. (The full text of Breckinridge’s speech is available in an articled published on the New York Times’ website). Breckinridge, as the Mississippian argued, “had always been the able and faithful champion of ‘the Union, the Constitution, and the equality of the States.’” Breckinridge attempted to bridge the sectional divide after Lincoln’s victory in November 1860, but twelve months after the election he joined the Confederate army as a brigadier general.

24

Jul

10

The Courtship of James Garfield

Posted by hardyr Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Education & Culture, Women & Families In 1847, Zeb and Arabella Rudolph decided that their daughter Lucretia needed more of an academic challenge than the local Garrettsville, Ohio, schools could offer. The fifteen-year old was sent twenty miles away to board at the Geauga Seminary, where she would have the benefit of a classical curriculum. The Geauga Seminary was coeducational, and one of Lucretia’s fellow pupils there was an awkward and earnest sixteen-year old boy named James Garfield.

In 1847, Zeb and Arabella Rudolph decided that their daughter Lucretia needed more of an academic challenge than the local Garrettsville, Ohio, schools could offer. The fifteen-year old was sent twenty miles away to board at the Geauga Seminary, where she would have the benefit of a classical curriculum. The Geauga Seminary was coeducational, and one of Lucretia’s fellow pupils there was an awkward and earnest sixteen-year old boy named James Garfield.

“A prodigy,” Lucretia called him.

In 1850, Lucretia left the Geauga Seminary and enrolled in the new Hiram Eclectic Institute in Hiram, Ohio. The following year, Garfield also enrolled at Hiram, and Lucretia experienced the unexpected thrill of meeting “a pair of eyes…as once I looked up from a hard sentence somewhere in the fore part of the Greek grammar.” It wasn’t exactly love at first conjugation—both she and James were recovering from painful break-ups—but in 1853 James surprised Lucretia with a letter written during an excursion to Niagara Falls, and soon the two were engaged in a full-fledged correspondence.

At first, they addressed each other as Brother and Sister. They wrote about the books they were reading, and about their shared enthusiasm for teaching. James was teaching Latin and Greek at Hiram, and Lucretia was teaching at a public school in Chagrin Falls, and attempting to keep pace with James’s Latin class in reading Virgil.

“I would like to know how many hundred lines the Virgil class are ahead of me,” she wrote to James in November 1853.

“Today, the Virgil class finished the third book and are going about 50 lines per day,” Jame wrote back on December 8. “Are you ahead? I presume so. Won’t you come in to both Greek and Latin in the spring? We miss you very much in these two classes. What are your views with regard to studying the classics? Have you reconciled yourself to devoting a few more years to them? I would like to hear your reasonings on the subject.”

Replying six days later, Lucretia confessed that she had laid aside Virgil for the winter. As to the study of classics in general, she wrote: “Candidly, I will confess that thus far I have prosecuted the study of them without any argument in their favor which appeared to me conclusive.” She admitted that the study of Greek and Latin provided “rigid mental discipline,” but she wondered if there might be other means of acquiring that discipline.

“I wish you would convince me of their superior merit if they really possess it,” she wrote; “for I do not like to give them up—neither do I like to continue in them feeling that precious moments are being wasted…”

This discussion continued in several letters over the following months. Meanwhile, James quietly dropped the pretense of calling her Sister, and soon Lucretia was sending James her “warmest love.” In March 1854, the subject of marriage was raised.

James A. Garfield—veteran of Shiloh and Chickamauga, Union general, and twentieth President of the United States—courted his wife with a debate over the value of a classical education.

The correspondence of James and Lucretia Garfield can be found in John Shaw, ed. Crete and James: Personal Letters of Lucretia and James Garfield (Michigan State University Press 1994). For a biography of Lucretia Garfield, see John Shaw, Lucretia (Nova History Publications, 2001). On James Garfield’s study of the classics, see Susan Ford Wiltshire’s essay, “The Classicist President” (.pdf).