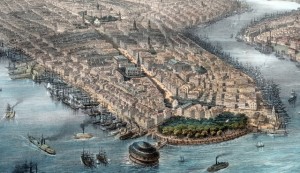

One hundred fifty years ago today the Charleston (SC) Mercury published part of New York City Mayor Fernando Wood’s speech that he gave during President-Elect Abraham Lincoln’s visit in late February 1861. Lincoln had left his home in Springfield, Illinois on February 11 for Washington DC. On the way he stopped at a number of cities, including Albany, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia. While Lincoln arrived in New York City with his wife on February 19, he did not meet with Mayor Wood until the afternoon of February 20. The Charleston (SC) Mercury described “Mayor Wood’s address of welcome to the Abolition President” as “too good to be lost.” As Lincoln entered “office with… a disconnected and hostile people to reconcile,” Wood told the President-Elect that “it will require a high patriotism and an elevated comprehension of the whole country and its varied interests, opinions and prejudices to so conduct public affairs as to bring it back again to its former harmonious, consolidated and prosperous condition.” In addition, Wood warned that “[New York’s] material interests are paralyzed” and “her commercial greatness is endangered.” Yet Wood also supported southern Democrats and he wanted the crisis to be resolved through compromise. Wood noted that he expected Lincoln to use “peaceful and conciliatory means” to ensure the “restoration of fraternal relations between the States.” Lincoln responded the same day to Wood’s remarks, noting that “there is nothing that can ever bring me willingly to consent to the destruction of this Union.” The following day Lincoln left for Trenton, New Jersey. You can read more about President-Elect Lincoln’s journey from Springfield to Washington, DC in Harold Holzer’s Lincoln: President-Elect (2008).

One hundred fifty years ago today the Charleston (SC) Mercury published part of New York City Mayor Fernando Wood’s speech that he gave during President-Elect Abraham Lincoln’s visit in late February 1861. Lincoln had left his home in Springfield, Illinois on February 11 for Washington DC. On the way he stopped at a number of cities, including Albany, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia. While Lincoln arrived in New York City with his wife on February 19, he did not meet with Mayor Wood until the afternoon of February 20. The Charleston (SC) Mercury described “Mayor Wood’s address of welcome to the Abolition President” as “too good to be lost.” As Lincoln entered “office with… a disconnected and hostile people to reconcile,” Wood told the President-Elect that “it will require a high patriotism and an elevated comprehension of the whole country and its varied interests, opinions and prejudices to so conduct public affairs as to bring it back again to its former harmonious, consolidated and prosperous condition.” In addition, Wood warned that “[New York’s] material interests are paralyzed” and “her commercial greatness is endangered.” Yet Wood also supported southern Democrats and he wanted the crisis to be resolved through compromise. Wood noted that he expected Lincoln to use “peaceful and conciliatory means” to ensure the “restoration of fraternal relations between the States.” Lincoln responded the same day to Wood’s remarks, noting that “there is nothing that can ever bring me willingly to consent to the destruction of this Union.” The following day Lincoln left for Trenton, New Jersey. You can read more about President-Elect Lincoln’s journey from Springfield to Washington, DC in Harold Holzer’s Lincoln: President-Elect (2008).

25

Feb

11

Lincoln & NYC Mayor Fernando Wood

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Images Themes: Contests & Elections16

Feb

11

Lincoln Meets Grace Bedell

Posted by Matthew Pinsker Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Contests & Elections, Women & FamiliesJust 150 years ago today on Saturday afternoon, February 16, 1861, President-Elect Abraham Lincoln met twelve-year-old Grace Bedell on a train platform in Westfield, New York. Showing off his new facial hair, he kissed the young girl and reportedly said, ““You see I have let these whiskers grow for you, Grace.”

If you know this story, then you’re either a Civil War buff or a very attentive sixth-grader. The year before Grace Bedell had written presidential candidate Abe Lincoln (whom she addressed as “Hon. A.B. Lincoln”) in October 1860 from her family’s temporary residence in upstate New York, inquiring whether Lincoln had any daughters before urging him to “let your whisker grow” since “your face is so thin.” This is a charming story that many elementary school teachers describe in their classrooms because it conveys such an important message about empowerment. Young Grace had an endearing, childlike candor (“answer this letter right off” she wrote in closing) that apparently ignited the bored candidate’s fancy because he responded within days. “I regret the necessity of saying I have no daughters,” Lincoln replied, adding, “As to the whiskers, having never worn any, do you not think people would call it a piece of silly affectation if I were to begin it now?” The famous letters, however, have never before been exhibited in public until 2009 when they were brought together by the Library of Congress in an exhibition that is currently traveling around the country.

In Lincoln’s era, presidential candidates almost always stayed home and avoided making public statements. It was considered undignified and un-republican to seek the presidential office. Obviously a few things have changed, but at least one political truth has endured. Image mattered just as much then as now.

Most school children hear this much of the Lincoln-Bedell story at least once during their academic careers, and every Lincoln scholar knows about it. But until recently, nobody really believed there was any more to the relationship. After the war, Grace Bedell married a Union army veteran named George Billings. The couple moved to Kansas and forged a life on the western prairie. They had one son and no daughters. Every so often until her death in 1936, Grace Bedell Billings would make an appearance, consent to an interview, or respond to some new correspondent seeking details about her encounter with Lincoln. Yet the gun-toting homesteader seemed mostly indifferent to her recurring fifteen minutes of fame. Grandson George Billings wrote to Time magazine shortly after her death, thanking the editors for orchestrating a dramatization about her experience with Lincoln, and claiming credibly that one of her favorite expressions had always been, “I dislike making a fuss.” Today, Billings descendants are trying to raise funds to preserve her former home in Delphos, Kansas.

This effort received a boost in 2007 when a diligent Lincoln researcher named Karen Needles discovered a new letter from Grace Bedell to President Lincoln that was written in January 1864 and somehow had gotten overlooked in the voluminous files of the National Archives. “Do you remember before your election receiving a letter from a little girl residing at Westfield in Chautauqua Co. advising the wearing of whiskers as an improvement to your face,” Bedell asked, before informing the president in firm, clear handwriting, “I am that little girl grown to the size of a woman.” Young Grace had grown but her characteristic brashness remained. Reminding the president that he had signed his previous letter to her, “Your true friend and well-wisher,” Bedell asked, “Will you not show yourself my friend now?” It turned out that she wanted a job, but her reason was quite poignant. “My Father during the last few years lost nearly all his property,” she confided, “and although we have never known want, I feel that I ought and could do something for myself.” She had heard about “a large number of girls” who were “employed constantly and with good wages at Washington cutting Treasury notes and other things pertaining to that Department.” She wondered, “Could I not obtain a situation there?” The appeal closed by noting that her parents were “ignorant of this application” and gently pointing out that she had sent an earlier query to him that had gone unanswered. “Direct to this place” was the line that closed Grace Bedell’s third letter to Abraham Lincoln.

She never heard back from the president and never once mentioned this application in any of her post-war accounts. Yet there is some reason to believe that President Lincoln did respond to Grace’s request by writing to her parents directly. There have been many children’s books written about Grace Bedell, and most are inconsequential, but there has been one serious historical account produced by Fred Trump, a native of Westfield who ended up settling in Salina, Kansas, not far from the Billings farm in Delphos. That coincidence apparently drove Trump, a retired Department of Agriculture official, to prodigious effort in his research. He turned up many local accounts that appear nowhere else but in his 1977 book, Lincoln’s Little Girl.

Toward the end of his book, Trump relates how some members of the Bedell family claimed that President Lincoln tried to adopt Grace during the war. The author quoted from multiple accounts produced by a woman named Jennie Macomber, who had been a little girl herself in Westfield in 1860 and who later befriended members of the Bedell family. She recalled how they told her that the president had written Grace’s father during the war “and offered to adopt her as his own daughter.” Trump believed Macomber’s story, and corroborated it as much as he could, but also dutifully quoted several Lincoln experts who coolly dismissed the tale as “embroidery.” The late Roy P. Basler, editor of Lincoln’s Collected Works, informed Trump, “The Abraham Lincoln papers include no correspondence between Lincoln and the parents of Grace Bedell. The collections in this division are not known to contain any information corroborating this story.”

That was in 1977. But in 2007, there appeared this newly discovered letter that does offer at least some corroboration of the old family gossip. After reading the 1864 letter from Grace, it is easy to imagine that Abraham Lincoln responded to the story of the Bedell family’s financial struggles with a direct appeal to Grace’s father. The president might well have offered to have the young woman live in the White House while she worked as one of the war’s many Treasury Department girls. Too proud to admit his financial reversals, businessman Norman Bedell either declined or just ignored the unexpected offer. What seemed fanciful to Roy Basler, now appears more reasonable given this new letter. Of course, the irony is that like so much else in history, with more information, our certainty about the past suddenly seems far less secure.

21

Jan

11

“Causes of Excessive Mortality in New York”

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals New York “is one of the most unhealthy cities on the globe” and, as the Lowell (MA) Citizen & News explained in March 1859, “the unhealthiness of the city” had once again “attract[ed] the attention of the legislators at Albany.” Two years later the situation in that city had not improved. After the health officer for New York City released a report in early 1861, James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald examined several of “the secret sources of excessive disease and death.” The Herald believed that while their city was “naturally more healthy than” any other one in North America, they noted that the “excessive mortality” rate did not reflect that fact. While the “filthy conditions” was an obvious “source of mortality,” other important factors included the lack of vaccination. The Herald argued that the city should follow the example of other countries like Sweden and enact “a compulsory law for vaccination.” If “the vaccination [for smallpox] has been perfectly performed,” the Herald explained that “the mortality is found to be uniformly reduced to less than one in every two hundred cases.” Immigrants were also identified as a cause of the “excessive mortality.” “Most of the children who die under one year of age are the offspring of foreigners” who had “recently arrived” in the United States, as the Heraldclaimed. Other factors included abortions through “violent means” and those “killed…by quack medicine.” Yet not all cities faced this kind of health crisis. An editorial in the Cleveland (OH) Herald was optimistic as the city’s mortality rate had declined even as the city’s population increased. “The introduction of pure water in unlimited quantity has doubtless had much to do with the improved sanitary condition of the city,” as the Cleveland Herald explained.

New York “is one of the most unhealthy cities on the globe” and, as the Lowell (MA) Citizen & News explained in March 1859, “the unhealthiness of the city” had once again “attract[ed] the attention of the legislators at Albany.” Two years later the situation in that city had not improved. After the health officer for New York City released a report in early 1861, James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald examined several of “the secret sources of excessive disease and death.” The Herald believed that while their city was “naturally more healthy than” any other one in North America, they noted that the “excessive mortality” rate did not reflect that fact. While the “filthy conditions” was an obvious “source of mortality,” other important factors included the lack of vaccination. The Herald argued that the city should follow the example of other countries like Sweden and enact “a compulsory law for vaccination.” If “the vaccination [for smallpox] has been perfectly performed,” the Herald explained that “the mortality is found to be uniformly reduced to less than one in every two hundred cases.” Immigrants were also identified as a cause of the “excessive mortality.” “Most of the children who die under one year of age are the offspring of foreigners” who had “recently arrived” in the United States, as the Heraldclaimed. Other factors included abortions through “violent means” and those “killed…by quack medicine.” Yet not all cities faced this kind of health crisis. An editorial in the Cleveland (OH) Herald was optimistic as the city’s mortality rate had declined even as the city’s population increased. “The introduction of pure water in unlimited quantity has doubtless had much to do with the improved sanitary condition of the city,” as the Cleveland Herald explained.

17

Dec

10

History Now – Underground Railroad Essay

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images, Recent ScholarshipThe Gilder Lehrman Institute recently published a new essay by House Divided co-director Matthew Pinsker in their December 2010 issue of History Now. As Pinsker explains in “The Underground Railroad and the Coming of War”:

“The Underground Railroad was a metaphor. Yet many textbooks treat it as an official name for a secret network that once helped escaping slaves. The more literal-minded students end up questioning whether these fixed escape routes were actually under the ground. But the phrase “Underground Railroad” is better understood as a rhetorical device that compared unlike things for the purpose of illustration. In this case, the metaphor described an array of people connected mainly by their intense desire to help other people escape from slavery. Understanding the history of the phrase changes its meaning in profound ways.”

You can read the full essay here. Other essays in this issue include “Lincoln’s Interpretation of the Civil War” by Eric Foner, “The Riddles of ‘Confederate Emancipation’” by Bruce Levine, and “Women and the Home Front: New Civil War Scholarship” by Catherine Clinton. All of the past issues of History Now are available here.

6

Dec

10

New York Times Features House Divided Image

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images Themes: Carlisle & Dickinson, Contests & Elections A blog post by Jamie Malanowski in the New York Times’ “Disunion” series featured this political cartoon from House Divided’s image collection. In this entry Malanowski explores how President James Buchanan addresses the secession crisis in his last State of the Union message to Congress in December 1860. “Buchanan at long last waded into the secession crisis…in the manner of a cranky grandfather who has found a pleasant afternoon nap spoiled by a household of fractious children,” as Malanowski describes. (Read the full text of Buchanan’s State of the Union here).This post is part of a new series that, as the New York Times explains, “revisits and reconsiders America’s most perilous period — using contemporary accounts, diaries, images and historical assessments to follow the Civil War as it unfolded.” Other entries include “Two Communiqués, and a Commander’s Dilemma,” “Silencing the Fanatics,” and “An American Thanksgiving, Skewered and Roasted.” You can also learn more about Buchanan from his profile on House Divided or at the James Buchanan Resource Center.

A blog post by Jamie Malanowski in the New York Times’ “Disunion” series featured this political cartoon from House Divided’s image collection. In this entry Malanowski explores how President James Buchanan addresses the secession crisis in his last State of the Union message to Congress in December 1860. “Buchanan at long last waded into the secession crisis…in the manner of a cranky grandfather who has found a pleasant afternoon nap spoiled by a household of fractious children,” as Malanowski describes. (Read the full text of Buchanan’s State of the Union here).This post is part of a new series that, as the New York Times explains, “revisits and reconsiders America’s most perilous period — using contemporary accounts, diaries, images and historical assessments to follow the Civil War as it unfolded.” Other entries include “Two Communiqués, and a Commander’s Dilemma,” “Silencing the Fanatics,” and “An American Thanksgiving, Skewered and Roasted.” You can also learn more about Buchanan from his profile on House Divided or at the James Buchanan Resource Center.

3

Dec

10

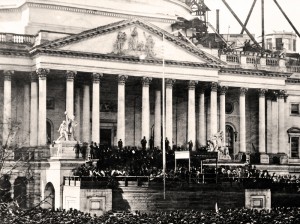

Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address – “A Scurvy Trick”

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Historic Periodicals, Recent Scholarship Themes: Contests & Elections Newspapers across the country published President Abraham Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address in March 1861, but not all included the correct version. Editors in New Orleans had, as the Chicago (IL) Tribune explained, “horribly botched” the speech. Not only had “words [been] altered,” but sentences [were] cut in two in the middle and other sentences [were] run together.” As a result, Lincoln’s speech had been turned “into a ridiculous jumble and mass of nonsense.” While Tribune editor Joseph Medill knew from experience that “a long document [rarely] is transmitted over the wires without undergoing more or less transformation,” he believed in this case that New Orleans editors deliberately included errors in order to further their disunion agenda. “Evidently the conductors of the secession press are unwilling that the people whom they have hurried into rebellion without a cause, shall have the opportunity of learning the truth or of listening to exhortations of loyalty,” as Medill concluded. The only “parallel instance of meanness” that Medill could recall had occurred during the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. As the Tribune noted in September 1858, Democratic editors told their reporters “to report [Lincoln’s speeches] incorrectly, to leave out words and sentences, and otherwise to mutilate his arguments so as to destroy their force and effect on the minds of those who read the Douglas papers.” You can read more about the Lincoln-Douglas debates in Michael Burlingame’s “Mucilating Douglas and Mutilating Lincoln: How Shorthand Reporters Covered the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858,” Lincoln Herald (1994) and Allen C. Guelzo’s Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America (2008). As for President Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, see chapter 3 of Douglas L. Wilson’s Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (2006).

Newspapers across the country published President Abraham Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address in March 1861, but not all included the correct version. Editors in New Orleans had, as the Chicago (IL) Tribune explained, “horribly botched” the speech. Not only had “words [been] altered,” but sentences [were] cut in two in the middle and other sentences [were] run together.” As a result, Lincoln’s speech had been turned “into a ridiculous jumble and mass of nonsense.” While Tribune editor Joseph Medill knew from experience that “a long document [rarely] is transmitted over the wires without undergoing more or less transformation,” he believed in this case that New Orleans editors deliberately included errors in order to further their disunion agenda. “Evidently the conductors of the secession press are unwilling that the people whom they have hurried into rebellion without a cause, shall have the opportunity of learning the truth or of listening to exhortations of loyalty,” as Medill concluded. The only “parallel instance of meanness” that Medill could recall had occurred during the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858. As the Tribune noted in September 1858, Democratic editors told their reporters “to report [Lincoln’s speeches] incorrectly, to leave out words and sentences, and otherwise to mutilate his arguments so as to destroy their force and effect on the minds of those who read the Douglas papers.” You can read more about the Lincoln-Douglas debates in Michael Burlingame’s “Mucilating Douglas and Mutilating Lincoln: How Shorthand Reporters Covered the Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858,” Lincoln Herald (1994) and Allen C. Guelzo’s Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America (2008). As for President Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, see chapter 3 of Douglas L. Wilson’s Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (2006).

1

Dec

10

Journal Divided featured on C-SPAN

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Recent Scholarship, Video “American History TV” on C-SPAN 3 featured an episode inside the classroom of House Divided Project co-director Matthew Pinsker. C-SPAN cameras followed Pinsker as he led a discussion about Abraham Lincoln and the election of 1860 for a class at Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA. During the session, Pinsker premiered a documentary short film recently created for Journal Divided. “Honest Abe” is one of six videos created to support new interactive essays based on excerpts from the unedited manuscript of Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008). Other essays include “Writing Lincoln’s Lives,” “Railsplitter,” and “Make No Contracts.”

“American History TV” on C-SPAN 3 featured an episode inside the classroom of House Divided Project co-director Matthew Pinsker. C-SPAN cameras followed Pinsker as he led a discussion about Abraham Lincoln and the election of 1860 for a class at Dickinson College in Carlisle, PA. During the session, Pinsker premiered a documentary short film recently created for Journal Divided. “Honest Abe” is one of six videos created to support new interactive essays based on excerpts from the unedited manuscript of Michael Burlingame’s Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008). Other essays include “Writing Lincoln’s Lives,” “Railsplitter,” and “Make No Contracts.”

You can watch the full 75-minute episode on C-SPAN’s website.

19

Nov

10

Election of 1860 – William Wilkins Letter

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Letters & Diaries Themes: Carlisle & Dickinson, Contests & Elections William Wilkins’ letter to James Webb, editor and publisher of the New York Courier and Enquirer, reveals an interesting view on some of the political perspectives that existed on the eve of the 1860 election. Wilkins, who graduated from Dickinson College in 1802, was a Pennsylvania Democratic politician who also served as Secretary of War in President John Tyler’s administration. While Wilkins had originally “intended to have told you something of myself,” he noted that Webb’s political “pamphlet has driven all such things out of my head and set if off ‘a wool gathering.’” Wilkins’ was not happy with Webb’s take on slavery. George Washington “never dreaming he was fighting for kidnapped Africans of the Lowest order of human beings,” Wilkins argued. Wilkins also believed that southerners should be allowed to bring slaves into any territory. “Where is the great right of migration?,” Wilkins asked. Yet Wilkins was careful to note that he did not count Webb among the radical abolitionists. “You must not suppose I include you…in [the] certain mad, fanatical category as full of political wickedness as was John Brown,” Wilkins explained. Wilkins hoped that sectional tensions would be resolved without resorting to disunion, as there could be no “secession, without pulling down the entire wonderfully and wildly constructed fabric” of the Union. While Wilkins’ wife asked him “to burn…this horrible letter,” he refused and sent it onto Webb. You can read the full text of this letter online at House Divided.

William Wilkins’ letter to James Webb, editor and publisher of the New York Courier and Enquirer, reveals an interesting view on some of the political perspectives that existed on the eve of the 1860 election. Wilkins, who graduated from Dickinson College in 1802, was a Pennsylvania Democratic politician who also served as Secretary of War in President John Tyler’s administration. While Wilkins had originally “intended to have told you something of myself,” he noted that Webb’s political “pamphlet has driven all such things out of my head and set if off ‘a wool gathering.’” Wilkins’ was not happy with Webb’s take on slavery. George Washington “never dreaming he was fighting for kidnapped Africans of the Lowest order of human beings,” Wilkins argued. Wilkins also believed that southerners should be allowed to bring slaves into any territory. “Where is the great right of migration?,” Wilkins asked. Yet Wilkins was careful to note that he did not count Webb among the radical abolitionists. “You must not suppose I include you…in [the] certain mad, fanatical category as full of political wickedness as was John Brown,” Wilkins explained. Wilkins hoped that sectional tensions would be resolved without resorting to disunion, as there could be no “secession, without pulling down the entire wonderfully and wildly constructed fabric” of the Union. While Wilkins’ wife asked him “to burn…this horrible letter,” he refused and sent it onto Webb. You can read the full text of this letter online at House Divided.

17

Nov

10

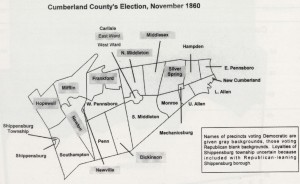

Election of 1860 – Cumberland County

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images, Recent Scholarship Themes: Carlisle & Dickinson, Contests & ElectionsWhile Abraham Lincoln was elected “by one of the largest voter turnouts in United States history,” historian Phillip Shaw Paludan notes that “the Republican victory was entirely sectional.” Lincoln and Hannibal Hamblin did not receive any votes from the Deep South states. Yet divisions also existed within northern states, including Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. The election results for Carlisle reflected a deep divide in the community – while Republicans won the town (overall votes in Carlisle West Ward / East Ward), Democrats received the most votes overall in Carlisle District (For more details, see election return tables below). As for Cumberland County, Lincoln received 51.5% of the vote in Cumberland County. These results largely correspond with historians’ arguments about urban and rural voting patterns in the 1860 election. While “one might expect to find northern cities to have been stronghold of Republicanism,” David Potter argues that “Lincoln received much less support in the urban North than he did in the rural North.” Republicans received the most votes by far in the rural precincts of Cumberland County and came very close to losing Carlisle. One can see which precinct Lincoln’s party won in the map below — precincts that Republicans won have blank backgrounds. This map was originally published in John Wesley Weigel’s “Free Soil: The Birth of the Republican Party in Cumberland County,” Cumberland County History Journal (Summer 2000). The full article, along with other essays that explore the political history of the Whigs and Democrats in Cumberland County, are available on this post as PDF files.

(Click on the map to see larger version)

In addition, you can click the “Continue Reading” link below to see the detailed election returns for Cumberland County, Carlisle District, and Newville District below –

continue reading "Election of 1860 – Cumberland County"

8

Nov

10

New York Times Features House Divided Image

Posted by sailerd Published in Antebellum (1840-1861), Images Themes: Contests & Elections A blog post by Jamie Malanowski in the New York Times’ “Disunion” series featured this political cartoon from House Divided’s image collection. In this entry Malanowski explores Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 election. Malanowski’s post is part of a new series that, as the New York Times explains, “revisits and reconsiders America’s most perilous period — using contemporary accounts, diaries, images and historical assessments to follow the Civil War as it unfolded.” Other entries include “Hearing the Returns with Mr. Lincoln,” “The Abolitionist’s Epiphany,” “Head-Stompers, Wrench-Swingers and Wide Awakes,” and “A Slave Ship in New York.”

A blog post by Jamie Malanowski in the New York Times’ “Disunion” series featured this political cartoon from House Divided’s image collection. In this entry Malanowski explores Abraham Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 election. Malanowski’s post is part of a new series that, as the New York Times explains, “revisits and reconsiders America’s most perilous period — using contemporary accounts, diaries, images and historical assessments to follow the Civil War as it unfolded.” Other entries include “Hearing the Returns with Mr. Lincoln,” “The Abolitionist’s Epiphany,” “Head-Stompers, Wrench-Swingers and Wide Awakes,” and “A Slave Ship in New York.”