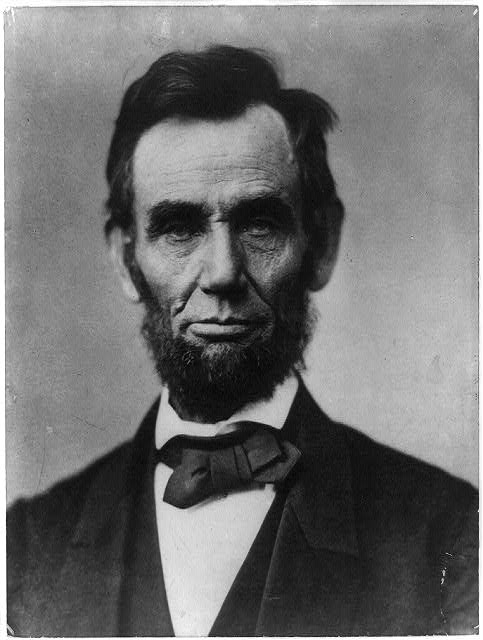

To honor Lincoln’s 205th birthday, we are tweeting out the top ten Lincoln resources from House Divided. But here is the full list:

To honor Lincoln’s 205th birthday, we are tweeting out the top ten Lincoln resources from House Divided. But here is the full list:

#1 Lincoln’s Writings: The Multi-Media Edition

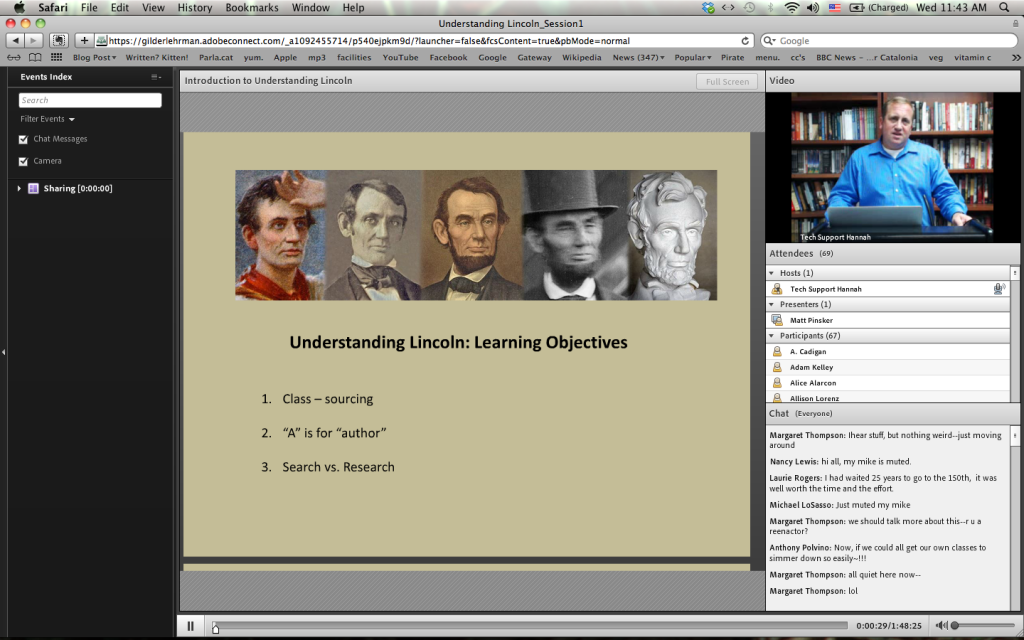

Created by participants in the “Understanding Lincoln” open online graduate course (offered in partnership with the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History), this site (still in development) features 150 of Lincoln’s “most teachable” documents and offers a full array of multi-media resources designed to help teach them in the K-12 and undergraduate classroom. This site is especially useful for Common Core alignments.

#2 Building the Digital Lincoln (Journal of American History)

Created as part of the Lincoln Bicentennial anniversary, this site offers a snapshot of where the “Digital Lincoln” stood as of 2009, and includes a host of examples of research and presentation tools, especially designed for serious student and academic scholars.

#3 Emancipation Digital Classroom

Created in part to help transform insights from James Oakes’s prize-winning study, Freedom National (2013) into use for the modern-day classroom, this site presents an array of primary and secondary source tools for studying the complicated but fascinating subject of emancipation and abolition.

#4 Unofficial Teacher’s Guide to Spielberg’s Lincoln

This “unofficial” guide includes access to Tony Kushner’s script, a full cast of characters (with photo comparisons to actual historical figures), and extensive analysis of the artistic license in the film and the historical reaction to Steven Spielberg’s important movie project.

#5 Lincoln-Douglas Debates Digital Classroom

This site offers a clickable word cloud of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and host of other rare primary sources for use in studying these critical texts.

#6 Abraham Lincoln in the House Divided Research Engine

The House Divided Research Engine is a Drupal-based content management system that contains over 12,000 public domain images and tens of thousands of documents and other historical records. The link above takes users directly to Abraham Lincoln’s main record page and offers a well-curated gateway for Lincoln research.

#7 Lincoln’s Gettysburg Addresses (Google Cultural Institute)

This short but compelling exhibit came together as part of the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address and helps visitors understand the evolution of the document, including a sharp analysis of all five manuscript versions of the address in Lincoln’s handwriting.

#8 Lincoln’s Autobiographical Sketch (YouTube & RapGenius)

Dickinson College students Leah Miller and Will Nelligan helped create short but engaging tools for studying Lincoln’s most important autobiographical writing –a sketch he produced in late 1859 to help launch his presidential bid. There is a six minute YouTube video of the sketch and an annotated edition of it through the new platform at RapGenius.

#9 Burlingame’s Lincoln Biography (Teaching Edition)

Michael Burlingame’s prize-winning Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2008) is the most important new multi-volume study of Lincoln, but it is difficult to teach because it is so lengthy. With permission, however, from both the author and the publisher (Johns Hopkins University Press), we have created short visually enhanced excerpts from the work that focus on the election of 1860 and include clickable footnotes, allowing teachers and students to “see” Burlingame’s sources directly.

#10 Mash Up of Collected Works, Lincoln Day-By-Day, and Lincoln Papers

Created by technologist Rafael Alvarado, this mash up includes an integrated interface allowing users to see the online edition of Lincoln’s Collected Works (his known writings), Lincoln Day-By-Day (his daily schedule), and The Abraham Lincoln Papers At the Library of Congress (the bulk of his extant correspondence) for the essential “one-stop” shopping experience. There is nothing else quite like this “timemap” available on the Internet –a must-see for serious and aspiring scholars.

Michael Lind

Michael Lind Richard Norton Smith might beg to disagree. Smith is one of the nation’s most prominent presidential historians. Currently a history faculty member at

Richard Norton Smith might beg to disagree. Smith is one of the nation’s most prominent presidential historians. Currently a history faculty member at  Like Richard Norton Smith, Craig Symonds tries to embody the classic scholarly caution about applying the past the to the present. Symonds taught for years in the History Department at the US Naval Academy. In fact, Symonds was the guy whom Harrison Ford “shadowed” in 1991 while he was studying up for his role as professor / spy Jack Ryan in the “The Patriot Games.” Symonds has authored or edited more than 20 history books, mostly on the Civil War or US naval history. He won the 2009 Lincoln Prize for his book,

Like Richard Norton Smith, Craig Symonds tries to embody the classic scholarly caution about applying the past the to the present. Symonds taught for years in the History Department at the US Naval Academy. In fact, Symonds was the guy whom Harrison Ford “shadowed” in 1991 while he was studying up for his role as professor / spy Jack Ryan in the “The Patriot Games.” Symonds has authored or edited more than 20 history books, mostly on the Civil War or US naval history. He won the 2009 Lincoln Prize for his book,