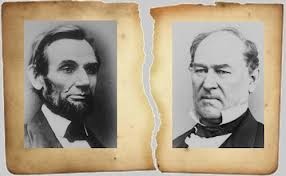

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his first letter to Fremont requesting changes in this proclamation, which he sent by special messenger from Washington just a few days later, Lincoln doesn’t sound so upset. He claimed only that two points in the fiery August 30 directive (which had also declared martial law) had given him “some anxiety.” The president dealt with the first matter regarding the shooting of people under the terms of Fremont’s martial law in blunt fashion, saying effectively, don’t do it without my approval, but then addressed the second matter concerning emancipation in a more subtle fashion. He asked Fremont to modify this part of the order “as of your own motion,” so that it would “conform” to the recent Confiscation Act (August 6, 1861) and claimed explicitly that he was making these confidential requests “in a spirit of caution, and not of censure.”

According to historian Louis Masur, Abraham Lincoln was “upset” by Union General John Fremont’s decision on August 30, 1861 to announce from his headquarters in St. Louis the general emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri (p. 28). Yet, in his first letter to Fremont requesting changes in this proclamation, which he sent by special messenger from Washington just a few days later, Lincoln doesn’t sound so upset. He claimed only that two points in the fiery August 30 directive (which had also declared martial law) had given him “some anxiety.” The president dealt with the first matter regarding the shooting of people under the terms of Fremont’s martial law in blunt fashion, saying effectively, don’t do it without my approval, but then addressed the second matter concerning emancipation in a more subtle fashion. He asked Fremont to modify this part of the order “as of your own motion,” so that it would “conform” to the recent Confiscation Act (August 6, 1861) and claimed explicitly that he was making these confidential requests “in a spirit of caution, and not of censure.”

Now this is a good example of how historians have to interpret evidence and how these interpretations actually matter. Masur believes Lincoln was upset because he thinks the Great Emancipator was still adamant in the summer of 1861 that the war was being fought over union and not slavery. That is why Masur claims that Lincoln found the Fremont proclamation so upsetting and “objectionable,” mainly because, as he puts it in The Civil War: A Concise History (2011), the order “violated the terms of the Crittenden-Johnson resolution, adopted by Congress on July 25, which reaffirmed the position that the war was not being fought to overthrow or interfere with established institutions” (28). Yet, Lincoln never mentioned that important (and very conservative-sounding) resolution in either of his two letters to Fremont. Nor did he use the word “objectionable” in his initial communication with Fremont, which Masur does not quote from in his short book.

Yet even in Lincoln’s second letter to Fremont, the one which Masur quotes from, the tone is not necessarily “upset.” Written in response to the general’s September 8th reply to his “private and confidential” September 2d telegram, the president still remained at least outwardly calm despite the fact that the general was stubbornly refusing to do what he had suggested. Fremont had actually sent his wife, Jesse Benton Fremont, an experienced politico herself, to deliver his response to the White House. She did so apparently around midnight on September 10, 1861. There was some kind of dramatic confrontation between Mrs. Fremont and President Lincoln that evening at the White House although its nature has been disputed. Two years later, the president recalled, according to the wartime diary of a close aide, that she “taxed me violently” during their conversation, although much of their argument by his recollection concerned rumors of Fremont’s administrative incompetence and factional politics in Missouri and not either martial law or emancipation (John Hay diary, December 9, 1863). This claim of the president’s is supported by a private memo from another White House aide (John Nicolay) produced just a week after the confrontation which asserted that the “matter of the Proclamation … did not enter into the trouble with the Gen” (September 17, 1861). Years later, Jesse Fremont remembered it much differently, claiming in 1891 that Lincoln was focused almost solely on the dangers of emancipation and had told her: “the General should never have dragged the Negro into the war.” This is not a very credible recollection, but it has appeared in various forms in many secondary sources and presumably helped inform Masur’s outlook. Regardless, what resulted from this unusual collision was a second presidential note, this time for public consumption, in which Lincoln claimed that while there was “no general objection” to Fremont’s August 30th order, on the particular matter of the “liberation of slaves,” there was something “objectionable” about its “non-conformity” with the Confiscation Act. So, Lincoln decreed, since the general wanted an “an open order for the modification” from the Commander-in-Chief himself, that he was “very cheerfully” willing to do so. Hence, the president publicly ordered on September 11, 1861, that Fremont’s proclamation was to be “modified” so as not to “transcend” the government’s official confiscation policy regarding the seizure of Rebel-employed slaves.

And there’s the rub. Some historians, like Masur, consider the official Union policy regarding slavery in the summer of 1861 to have remained what Lincoln had stated (or technically re-stated) in his March inaugural address. In his brief passage on Fremont’s controversial order, Masur writes, “The proclamation itself violated Lincoln’s assurance that he had no intentions of interfering with slavery where it existed” (28-29). Yet for other historians, such as James Oakes, that policy on non-interference had already changed –and had been changing since spring 1861. The August 6th Confiscation Act merely culminated a new wartime policy by Union authorities allowing them to interfere with slavery whenever it was necessary for military reasons. In particular, runaways or “contrabands” were generally supposed to be “discharged” from enslavement, because as the fourth section of the new statute delicately put it, any slaveholder who required or allowed “any person claimed to be held to labor or service” (i.e. his slaves) to either “take up arms” against the United States or to be employed by the Rebel military was to “forfeit his claim to such labor.” It’s not clear from the plain language of the statute that these ex-slaves were to be freed, but that was the practical effect in many cases. This new  precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as May 30, 1861 allowing them to protect so-called “contrabands” or fugitives from the demands of slaveholders, and on August 8, 1861, the Secretary of War (Simon Cameron) provided a clear directive based on the new law authorizing commanders to protect and discharge not only Rebel-employed slaves, but also runaways whose masters were loyal. Cameron’s letter informed field commanders (in this case, specifically General Benjamin Butler) that they should simply keep records of everyone freed so that later (“Upon the return of peace”), Congress could provide for “just compensation” to any loyal masters whose slaves had been “discharged” incorrectly. Not every Union commander followed this directive in the subsequent months, but more than a few did. The result was real freedom for many ex-slaves. At the end of the year, President Lincoln, in his first annual message, described the policy shift as one that had “thus liberated” an unspecified “numbers” of black people in 1861.

precarious freedom also applied indirectly to runaways who had nothing to do with the war effort. The War Department had begun issuing orders to field commanders as early as May 30, 1861 allowing them to protect so-called “contrabands” or fugitives from the demands of slaveholders, and on August 8, 1861, the Secretary of War (Simon Cameron) provided a clear directive based on the new law authorizing commanders to protect and discharge not only Rebel-employed slaves, but also runaways whose masters were loyal. Cameron’s letter informed field commanders (in this case, specifically General Benjamin Butler) that they should simply keep records of everyone freed so that later (“Upon the return of peace”), Congress could provide for “just compensation” to any loyal masters whose slaves had been “discharged” incorrectly. Not every Union commander followed this directive in the subsequent months, but more than a few did. The result was real freedom for many ex-slaves. At the end of the year, President Lincoln, in his first annual message, described the policy shift as one that had “thus liberated” an unspecified “numbers” of black people in 1861.

The interpretative stakes are quite high here. Masur (and many others) explicitly describe the Civil War as one that “began as a limited war to restore the country” (xi) before becoming in late 1862 and early 1863 a more revolutionary struggle for freedom. Yet if Lincoln was not so “upset” by Fremont’s 1861 emancipation decree, but rather more concerned over exactly how to emancipate slaves, then this emphasis on limited war seems misplaced. There was certainly plenty of limited, cautious rhetoric on the Union side, especially from President Lincoln, but the policies on the ground seem far more radical, almost right from the beginning. Yet it is complicated. On September 22, 1861, Lincoln defended his actions in regard to General Fremont in a remarkably candid private letter to his old friend, Orville Browning, now a U.S. senator from Illinois (he had recently taken the seat following the death of Stephen A. Douglas). Lincoln labeled Fremont’s emancipation edict “purely political” and

denied forcefully that either “a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation.” That sounds quite limited as a policy statement, and yet a smart Civil War student might well ask, isn’t that also exactly what the Great Emancipator himself did just one year later, when he revealed his own emancipation policy on September 22, 1862? With presidential emancipation, he made “permanent rules of property by proclamation.” In his letter to Browning –a must-read for any serious student– Lincoln denied that he had been or would be “inconsistent” and carefully explained to his longtime friend and political colleague the difference between “principle” and “policy” and why some things had to be done in private while others had to be managed in public. It’s a masterful document and one that holds perhaps the key to understanding Lincoln as a wartime political leader.

This post originally appeared at Matthew Pinsker’s Civil War & Reconstruction class (History 288), Dickinson College, Spring 2015.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post

Leave A Reply

Please Note: Comment moderation maybe active so there is no need to resubmit your comments