As a college student, I have always been both curious and skeptical about “online courses”. Although I have never taken one, I have often imagined the potential ease that learning at home would bring. Is this concept too good to be true though? Surely there must be a catch. As an intern at Dickinson College with Professor Pinsker (who is preparing to launch a new online course of his own titled, “Understanding Lincoln”) I have had the opportunity to do some additional research on this topic. What I have found so far, is a range of opinions that seem to only highlight my own mixed thoughts. In response, I will be writing a series of blog posts on the subject, comparing and contrasting some of the main points of these articles while bringing to light both the potential benefits and risks of online courses.

In an editorial for The New York Times Opinion Page, concerns for online learning and cautionary advice were deeply expressed. The article titled “The Trouble With Online College” from February 18, 2013, highlights the students rather than focusing on the professors and course itself. It uses recent studies to explain that the attrition rates for online courses are high, sometimes close to 90%. More specifically, The New York Times believes that the students damaged most are those who are vulnerable. The article classifies this group of people as those often barely prepared for a college setting, potentially having needs for more basic math and english classes, and often attending community colleges. It states, “A five-year study, issued in 2011, tracked 51,000 students enrolled in Washington State community and technical colleges. It found that those who took higher proportions of online courses were less likely to earn degrees or transfer to four-year colleges.” As a result, it proposes that these types of students should demonstrate their ability to learn first in a classroom, saying “Lacking confidence as well as competence, these students need engagement with their teachers to feel comfortable and to succeed. What they often get online is estrangement from the instructor who rarely can get to know them directly.” This concern is too big for The New York Times to ignore, and their article encourages universities to either improve online courses before opening them on a wide scale, or providing a hybrid option, which has proved to be more effective.

In an editorial for The New York Times Opinion Page, concerns for online learning and cautionary advice were deeply expressed. The article titled “The Trouble With Online College” from February 18, 2013, highlights the students rather than focusing on the professors and course itself. It uses recent studies to explain that the attrition rates for online courses are high, sometimes close to 90%. More specifically, The New York Times believes that the students damaged most are those who are vulnerable. The article classifies this group of people as those often barely prepared for a college setting, potentially having needs for more basic math and english classes, and often attending community colleges. It states, “A five-year study, issued in 2011, tracked 51,000 students enrolled in Washington State community and technical colleges. It found that those who took higher proportions of online courses were less likely to earn degrees or transfer to four-year colleges.” As a result, it proposes that these types of students should demonstrate their ability to learn first in a classroom, saying “Lacking confidence as well as competence, these students need engagement with their teachers to feel comfortable and to succeed. What they often get online is estrangement from the instructor who rarely can get to know them directly.” This concern is too big for The New York Times to ignore, and their article encourages universities to either improve online courses before opening them on a wide scale, or providing a hybrid option, which has proved to be more effective.

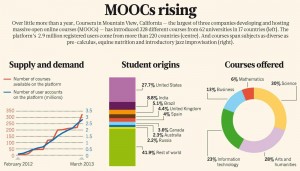

Taking a much different approach than The New York Times, is Steve Kolowich, a writer for The Chronicle of Higher Education. In his article titled “The Professors Who Make the MOOCS” from March 20, 2013, he gives recent and compelling evidence in favor of online learning, Kolowich broadly reviews the responses of the largest ever survey of online course instructors. The result, is an overwhelmingly positive portrayal. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCS) are the main focus of Kolowich’s article, in which he uses numerous generalizations from the statistics (103 responses) and personal statements from the professors themselves, in order to show their potential. Over 50% of the instructors, he says, believe that the online classes are as rigorous as classroom instruction, and many universities are now giving certificates for their completion. While most colleges do not offer these classes for credit, many believe that it is only a matter of time. Kolowich notes that, “The American Council on Education, a group that advises college presidents on policy, recently endorsed five MOOCs from Coursera for credit, and it is reviewing three from Udacity.” Although a wide variety of schools have adopted variations of online learning, the professors who are at the forefront of these massive online courses are from prestigious universities such as Harvard, MIT, and Duke. Despite many of them originally being skeptical of these courses, Kolowich says, “Now these high-profile professors, who make up most of the survey participants, are signaling a change of heart that could indicate a bigger shake-up in the higher-education landscape.” Two-thirds of the professors surveyed see MOOCS as potentially lowering the costs of earning a degree from their home institutions, and possibly making college less expensive in general. Kolowich goes on to discuss that while the time and effort for creating these courses is excessive, most professors list altruism, increased visibility, greater reach, and staying in the forefront as worthwhile reasons for adopting them. While some critics say that online learning decreases the need for classroom learning, Kolowich makes it clear that many professors in his survey see it instead as a way to help improve classroom education. He states that “A key way professors are learning new teaching tricks is by taking cues from their MOOC students. Coursera, edX, and Udacity all track the interactions each student has with the course materials, and with one another, within a given course. Each platform then gives professors the ability to see data that could tell them, for example, which methods and materials help students learn and which ones they find extraneous or boring.” This outlook expands on the possibilities and potential of online courses by viewing them not only as a course itself, but also as a  learning device for teachers.

learning device for teachers.

Despite such contrasting articles, one thing remains clear: online courses are racing to the forefront of education, and cannot be ignored. Kolowich, while focusing mainly on professors, portrays online courses positively, while The New York Times article focuses on the students and portrays online courses negatively. Even though The New York Times does not deny that some online courses may be successful, their article does bring about an important concern regarding certain students. I believe that each of these articles convey ideas that need to be equally examined. It appears to be true that there are many benefits to online education, and that many of these courses can be effective. However, with such great size, it is easy to overlook the students themselves. For any school offering an online class, I think it is crucial for them not to see students as numbers, but rather as individuals. This appears to be a difficult, if not impossible task. To benefit potential “borderline” students such as those expressed in The New York Times article, perhaps students should have to meet certain requirements before taking an online class in order to guarantee a higher success rate. In the end, there is still much to be discussed and thought about regarding this new and controversial subject. I am looking forward to reading more articles about these online courses, and using my student perspective to sort though them.

This post is part of a series on “Making History Online” that involves an examination of open online learning. Students and faculty at the House Divided Project at Dickinson College are collaborating this summer on a new open, online course called, “Understanding Lincoln,” taught by Prof. Matthew Pinsker and covering ways to teach Abraham Lincoln’s legacy using close readings of his most important writings. This new type of online course represents a unique partnership between Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. The course is available for both graduate credit and free participation. Registration for the course closes on Friday, July 19, 2013. For more information, go to https://www.gilderlehrman.org/programs-exhibitions/understanding-lincoln-graduate-course.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post

Leave A Reply

Please Note: Comment moderation maybe active so there is no need to resubmit your comments