A group of freedom seekers escape during the night. (House Divided Project)

A group of 14 enslaved Missourians escaped from St. Louis in early January 1850, traversing the frigid waters of the Mississippi river to reach free soil in Illinois. On the morning of January 16, however, eight of the escapees––two disabled men, one able-bodied man, three women and two children––were overtaken north of Springfield, Illinois by Constable Strother G. Jones and a posse of white men, eager to claim the hefty $2,400 reward offered for their recapture. What followed was a series of surprising twists and turns. Outside of Springfield, one-legged captive Hempstead Thornton swung his crutch and knocked Jones and two white accomplices unconscious, enabling the other seven freedom seekers to bolt. Five were recaptured, but escaped once again (this time for good) in the predawn hours of January 17. All but Thornton, that is, who gained his freedom not by physically eluding his captors, but rather in court. In a sweeping decision handed down months later, the Illinois Supreme Court not only declared Thornton to be free, but also struck down the state’s 1819 law providing for the recapture of runaway bond people. [1]

Hempstead Thornton’s oft-overlooked legal victory is one of many such court cases explored in Darrel Dexter’s richly detailed study, Bondage in Egypt (2011). Dexter, who teaches high school in southern Illinois, pored over court records, contemporary newspapers, and recollected accounts to reconstruct the struggle over slavery in “Egypt,” the moniker commonly applied to the southern counties of the state. He traces chattel slavery’s origins in the region back to 1720, when Jesuit missionaries imported more than two dozen enslaved Africans into French-controlled Kaskaskia. Slavery remained a legally sanctioned institution in Illinois throughout the 18th century, even after the territory’s incorporation into the nascent United States. [2]

Congress’s adoption of the Northwest Ordinance in 1787 seemingly barred slavery from the region, though a critical loophole allowed French citizens to continue to observe “their laws and customs now in force among them.” This provision was quickly construed by slaveholding Illinoisans as a protection for slavery. Slaveholders pushing a loose interpretation found a reliable ally in the Northwest Territory’s first governor, Arthur St. Clair, who insisted that the ordinance “was intended simply to prevent the introduction of other” enslaved people, not outlaw bondage altogether. St. Clair’s logic, argues Dexter, “established the Northwest Ordinance as a governmental plan that did not call for the immediate abolition of slavery in the territory,” and paved the way for a later territorial governor, William Henry Harrison, to pass an 1803 law sanctioning term slavery. Couched in the language of indentured servitude, the statute stipulated that any African-descent person who entered the territory could be bound to service, creating a system that in practice “was little different than chattel slavery in the South,” writes Dexter. The ensuing decades, moreover, saw an influx of white emigrants from Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia. The growing numbers of pro-slavery southerners, coupled with Egypt’s geographic location, hemmed in as it was by slaveholding Missouri to the west and slaveholding Kentucky to the south, transformed Egypt into a “quasi slave state,” Dexter claims. Slaveholders’ power over early Illinois politics was so entrenched, he maintains, that soon after attaining statehood, the Illinois legislature passed a law in 1819 calling for the arrest of any black person who was not carrying free papers. [3]

The end of term slavery in Illinois only came following a constitutional ban in 1848. By that time, the fertile border region was intensely divided over slavery. Most white Illinoisans living in Egypt found slavery to be anathema, but were also virulently racist and shuddered at the prospect of freed African Americans migrating to their state. Three years after the Illinois Supreme Court freed the Missouri runaway Thornton and overturned the 1819 law, the legislature passed a new statute barring the entry of free blacks. Through his detailed account of Illinois’s lengthy but often forgotten relationship with slavery, as well as the anti-black sentiments harbored by many white residents in Egypt, Dexter provides crucial context to understanding the social and political climate encountered by enslaved Missourians and Kentuckians as they wound through southern Illinois in their quest for freedom. [4]

Enslaved people escaping by boat. (House Divided Project)

Dexter devotes three lengthy chapters to examining the runaway bond people who passed through Egypt, as well as the black and white anti-slavery activists in the region who aided freedom seekers. In doing so, Dexter recounts a number of group escapes, though he does not use the term “stampede” to describe the mass flight of enslaved people. An 1835 case saw seven enslaved people escape from a U.S. army officer stationed in St. Louis, only to be recaptured in Illinois, along with two white men who reportedly assisted them, both of whom were hauled across the Mississippi and severely beaten by an anti-abolitionist mob. [5] Nearly a decade later in 1844, four enslaved people escaped from slaveholder James Bissell in St. Louis, successfully making their way to Chicago. There, the city’s abolitionist newspaper, the Western Citizen, openly mocked Bissell’s relentless attempts to re-enslave his erstwhile human property. The paper addressed a mocking communique to inform Bissell that “John and Lucy have arrived safely here, via the underground railroad.” [6] Sometime around 1849, John and Lucinda Henderson, along with their two children, escaped from St. Louis, spurred by news of an impending family separation. The family of four were helped across the Mississippi by a white woman named Susan Yates, then moved on foot to Alton, Illinois, where black activists helped them reach Chicago. [7] Around the same time, the January 1850 escape of some 14 enslaved people from St. Louis was labeled a “slave stampede” at the time by Springfield papers, though Dexter does not use the term. Instead, he primarily focuses on the case’s broader legal ramifications, highlighting the subsequent ruling of the Illinois Supreme Court. [8]

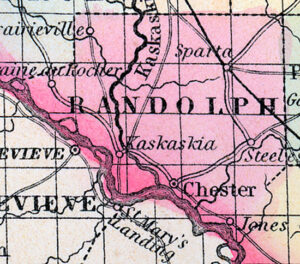

Located directly across the river from Ste. Genevieve, Randolph county, Illinois was the site of two violent clashes between freedom seekers and slave catchers in the late 1850s. (House Divided Project)

Bondage in Egypt also examines two largely overlooked group escapes from eastern Missouri during the late 1850s, both of which culminated in violent confrontations. In June 1857, four enslaved people escaped from Iron Mountain in St. Francois county, Missouri, but were overtaken by a posse of white men at Gravel Creek Bridge, located near the riverside town of Chester, Illinois. In a pair of violent clashes, two of the freedom seekers were killed, one severely wounded and recaptured, while one managed to successfully escape. A pro-slavery mob afterwards decapitated the corpse of John Scott, one of the slain escapees. Two white Illinoisans, who had opened fire on the enslaved Missourians, were charged with manslaughter, but later acquitted in 1861. [9]

Little more than two years later in September 1859, five enslaved people escaped from Fredericktown, Missouri, but were pursued by a sizable group of Missourians, who intercepted the freedom seekers at Gravel Creek Bridge (the site of the 1857 conflict). In the ensuing fight, one enslaved man was killed, while the other four escaped, though at least two were wounded in the fray. However, local authorities in Illinois arrested a white Missourian for murder, prompting a mob of upwards of 50 angry southerners to cross the Mississippi in protest. The stand-off did not escalate into outright violence, though pro-slavery Missourian responded by charging two Fredericktown residents with slave stealing under a Missouri statute. [10]

Dexter’s book is an invaluable repository of information regarding slavery in Illinois itself, but it is the volume’s robust trove of insights on Missouri freedom seekers that are of especial interest to this project. Bondage in Egypt harnesses newspaper accounts and court records to shine a light on little-known group escapes from eastern Missouri, revealing critical new details about the mass flights from bondage which contemporaries so often styled “slave stampedes.”

[1] Darrel Dexter, Bondage in Egypt: Slavery in Southern Illinois (Cape Girardeau, MO: Center for Regional History, Southeast Missouri State University, 2011) 271-274.

[2] Dexter, 14-17, 24-25.

[3] Dexter, 14-17, 48-50, 69-71, 248.

[4] Dexter, 10-11,17.

[5] Dexter, 259-260.

[6] Dexter, 318.

[7] Dexter, 330. According to Dexter, the same Susan Yates may have also been convicted of “enticing” another bond person away in 1844.

[8] Dexter, 273-274. On contemporary newspapers’ use of the word stampede when describing the January 1850 escape, as well as the episode’s intriguing connections to future president Abraham Lincoln, see this post.

[9] Dexter, 313-315.

[10] Dexter, 285. Also see “A Batch of Runaway Negroes––Excitement in Randolph County, Ill.,” St. Louis, MO Republican, October 8, 1859. The report in the St. Louis Republican describes the group of five freedom seekers as part of a larger “batch” of “ten or fifteen slaves” who had escaped from the vicinity of Fredericktown, and had “stirred up considerable feeling in that part of this State.” The account also noted that the five escapees Dexter refers to had “joined some of those who had previously escaped” from Fredericktown, and were “furnished with fire-arms.”

Darrel Dexter is an amazing historian who quietly works in educating adults as well as his students! Thank you for sharing this with a much larger audience!