Contributing Editors for this page include Jonas Sherr

Ranking

#138 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.’ When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy.”

On This Date

HD Daily Report, August 24, 1855

The Lincoln Log, August 24, 1855

Close Readings

Jonas Sherr, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), Sep. 30, 2013

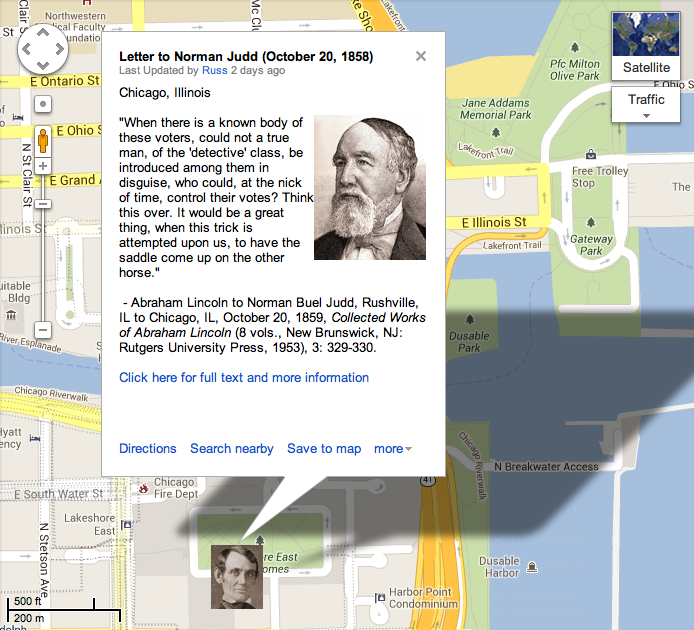

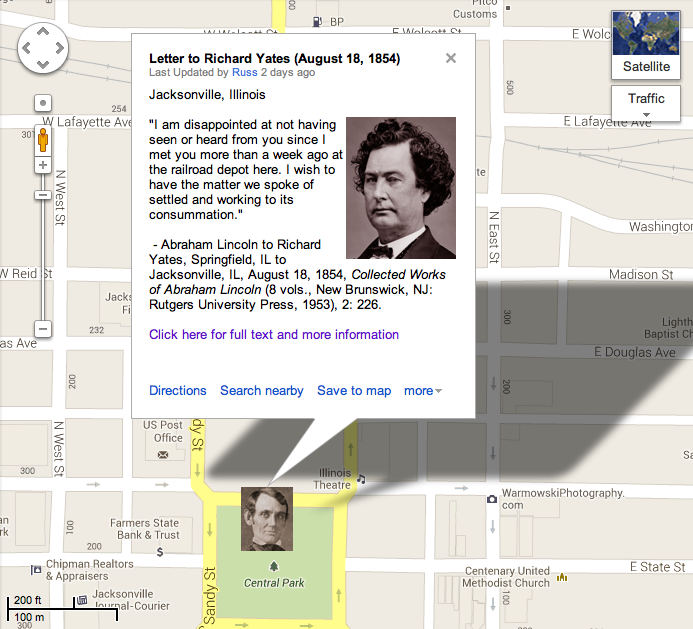

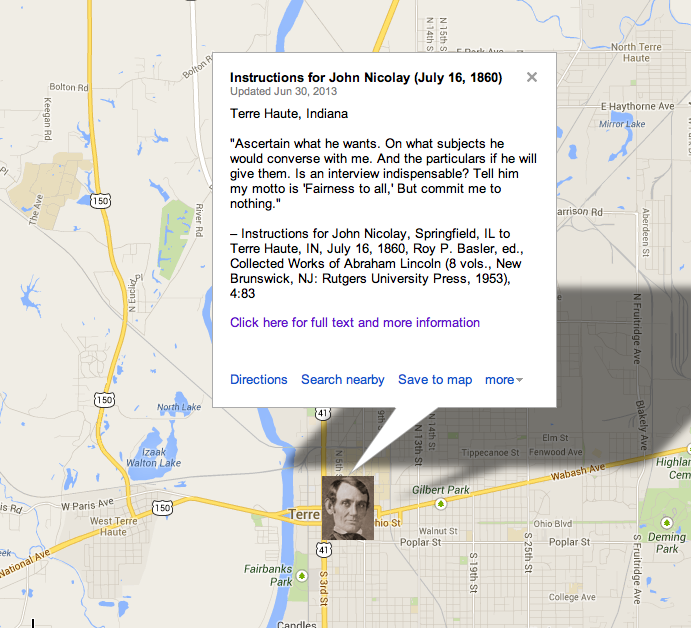

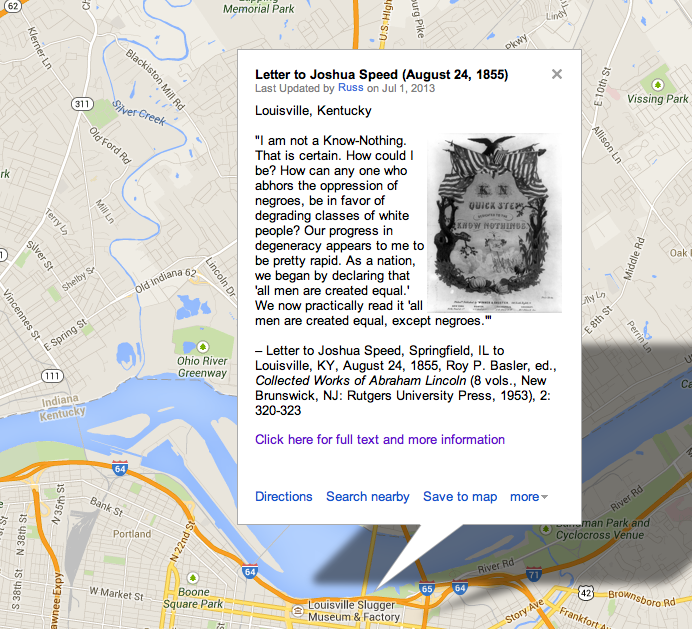

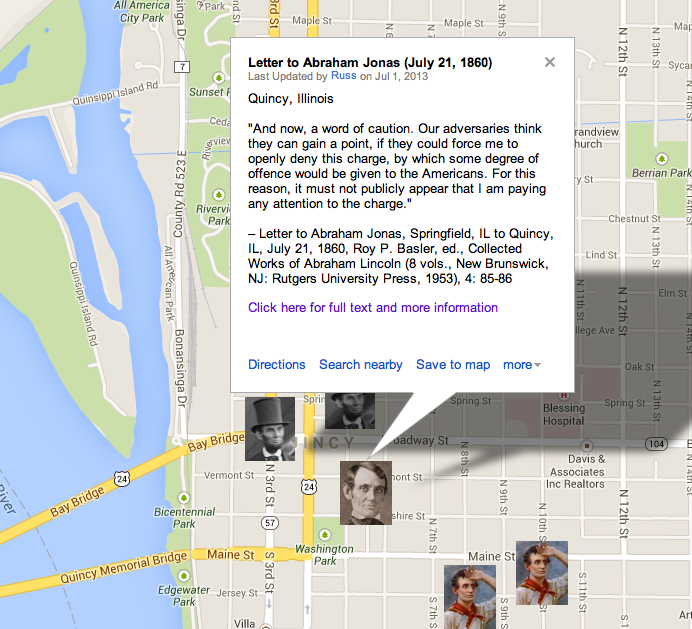

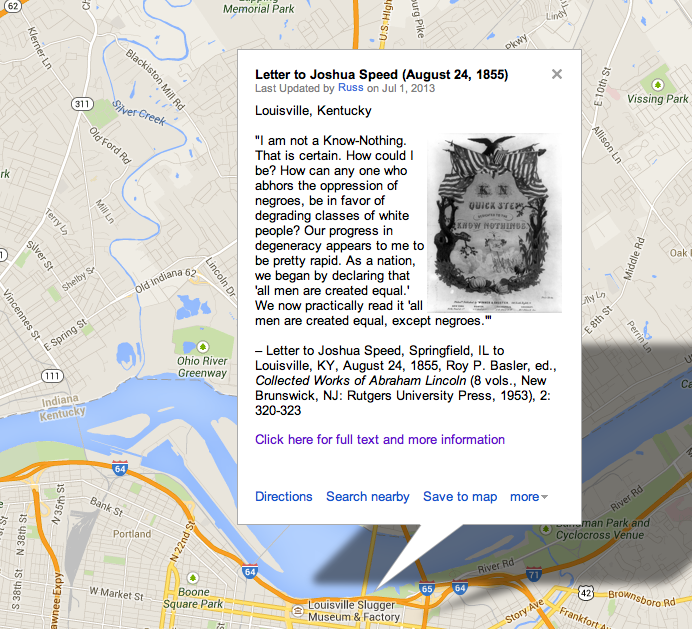

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

How Historians Interpret

“In response to Speed’s professed willingness to dissolve the Union if the rights of slaveholders were violated, Lincoln said that he would not attempt to do so if the tables were turned and Kansas were admitted as a Slave State. To be sure, Speed had expressed the hope that Kansas would be admitted as a Free State; but, Lincoln rejoined, slaveholders’ deeds belied their words. ‘All decent slave-holders talk that way; and I do not doubt their candor. But they never vote that way.’ In private correspondence or conversation, ‘you will express your preference that Kansas shall be free,’ but ‘you would vote for no man for Congress who would say the same thing publicly.’ Echoing his 1854 Peoria address, Lincoln told his old friend that ‘slave-breeders and slave traders, are a small, odious and detested class, among you; and yet in politics, they dictate the course of all of you, and are as completely your masters, as you are the masters of your own negroes.’ Though dubious about the prospects for a free Kansas, Lincoln said he would work for that cause: ‘In my humble sphere, I shall advocate the restoration of the Missouri Compromise, so long as Kansas remains a territory; and when, by all these foul means, it seeks to come into the Union as a Slave-state, I shall oppose it.'”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 1, Chapter 11 (PDF), 1165.

“Lincoln’s frequent assertions of his Whig loyalty echoed a similar commitment to party policies, values and outlook. As Daniel Howe has suggested, Lincoln’s Whiggery ‘sprang from the very depths of his being’ and remained an intense, deeply imbedded part of him. That is why it was so difficult for Lincoln to leave the Whig party in the fifties. He hesitated even as political conditions changed sharply and the party’s fortunes collapsed. He continued to say, ‘I think I am a whig,’ even when others suggested that there no longer were any Whigs. For a long time he claimed that he saw no reason to join a new party.”

— Joel H. Silbey, “’Always a Whig in Politics’ The Partisan Life of Abraham Lincoln,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 8, no. 1 (1986): 21-42.

“Lincoln had nothing but disdain for the discriminatory beliefs of the Know Nothings. ‘How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people?’ he queried his friend Joshua Speed. ‘Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes.’ When Know-Nothings get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.’ When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance.’ But this party, too, was soon to founder on the issue of slavery. Many Northern Know Nothings were also antislavery, and finally the anti-Nebraska cause proved more compelling, of more import, than resistance to foreign immigration.”

–Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), 180-181.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

Springfield, Aug: 24, 1855

Dear Speed:

You know what a poor correspondent I am. Ever since I received your very agreeable letter of the 22nd. of May I have been intending to write you in answer to it. You suggest that in political action now, you and I would differ. I suppose we would; not quite as much, however, as you may think. You know I dislike slavery; and you fully admit the abstract wrong of it. So far there is no cause of difference. But you say that sooner than yield your legal right to the slave—especially at the bidding of those who are not themselves interested, you would see the Union dissolved. I am not aware that any one is bidding you to yield that right; very certainly I am not. I leave that matter entirely to yourself. I also acknowledge your rights and my obligations, under the constitution, in regard to your slaves. I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils; but I bite my lip and keep quiet. In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a Steam Boat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continual torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border. It is hardly fair for you to assume, that I have no interest in a thing which has, and continually exercises, the power of making me miserable. You ought rather to appreciate how much the great body of the Northern people do crucify their feelings, in order to maintain their loyalty to the constitution and the Union.

I do oppose the extension of slavery, because my judgment and feelings so prompt me; and I am under no obligation to the contrary. If for this you and I must differ, differ we must. You say if you were President, you would send an army and hang the leaders of the Missouri outrages upon the Kansas elections; still, if Kansas fairly votes herself a slave state, she must be admitted, or the Union must be dissolved. But how if she votes herself a slave state unfairly—that is, by the very means for which you say you would hang men? Must she still be admitted, or the Union be dissolved? That will be the phase of the question when it first becomes a practical one. In your assumption that there may be a fair decision of the slavery question in Kansas, I plainly see you and I would differ about the Nebraska-law. I look upon that enactment not as a law, but as violence from the beginning. It was conceived in violence, passed in violence, is maintained in violence, and is being executed in violence. I say it was conceived in violence, because the destruction of the Missouri Compromise, under the circumstances, was nothing less than violence. It was passed in violence, because it could not have passed at all but for the votes of many members, in violent disregard of the known will of their constituents. It is maintained in violence because the elections since, clearly demand it’s repeal, and this demand is openly disregarded. You say men ought to be hung for the way they are executing that law; and I say the way it is being executed is quite as good as any of its antecedents. It is being executed in the precise way which was intended from the first; else why does no Nebraska man express astonishment or condemnation? Poor Reeder is the only public man who has been silly enough to believe that any thing like fairness was ever intended; and he has been bravely undeceived.

That Kansas will form a Slave constitution, and, with it, will ask to be admitted into the Union, I take to be an already settled question; and so settled by the very means you so pointedly condemn. By every principle of law, ever held by any court, North or South, every negro taken to Kansas is free; yet in utter disregard of this—in the spirit of violence merely—that beautiful Legislature gravely passes a law to hang men who shall venture to inform a negro of his legal rights. This is the substance, and real object of the law. If, like Haman, they should hang upon the gallows of their own building, I shall not be among the mourners for their fate.

In my humble sphere, I shall advocate the restoration of the Missouri Compromise, so long as Kansas remains a territory; and when, by all these foul means, it seeks to come into the Union as a Slave-state, I shall oppose it. I am very loth, in any case, to withhold my assent to the enjoyment of property acquired, or located, in good faith; but I do not admit that good faith, in taking a negro to Kansas, to be held in slavery, is a possibility with any man. Any man who has sense enough to be the controller of his own property, has too much sense to misunderstand the outrageous character of this whole Nebraska business. But I digress. In my opposition to the admission of Kansas I shall have some company; but we may be beaten. If we are, I shall not, on that account, attempt to dissolve the Union. On the contrary, if we succeed, there will be enough of us to take care of the Union. I think it probable, however, we shall be beaten. Standing as a unit among yourselves, you can, directly, and indirectly, bribe enough of our men to carry the day—as you could on an open proposition to establish monarchy. Get hold of some man in the North, whose position and ability is such, that he can make the support of your measure—whatever it may be—a democratic party necessity, and the thing is done. Appropos of this, let me tell you an anecdote. Douglas introduced the Nebraska bill in January. In February afterwards, there was a call session of the Illinois Legislature. Of the one hundred members composing the two branches of that body, about seventy were democrats. These latter held a caucus, in which the Nebraska bill was talked of, if not formally discussed. It was thereby discovered that just three, and no more, were in favor of the measure. In a day or two Douglas’ orders came on to have resolutions passed approving the bill; and they were passed by large majorities!!! The truth of this is vouched for by a bolting democratic member. The masses too, democratic as well as whig, were even, nearer unanamous against it; but as soon as the party necessity of supporting it, became apparent, the way the democracy began to see the wisdom and justice of it, was perfectly astonishing.

You say if Kansas fairly votes herself a free state, as a christian you will rather rejoice at it. All decent slave-holders talk that way; and I do not doubt their candor. But they never vote that way. Although in a private letter, or conversation, you will express your preference that Kansas shall be free, you would vote for no man for Congress who would say the same thing publicly. No such man could be elected from any district in any slave-state. You think Stringfellow & Co ought to be hung; and yet, at the next presidential election you will vote for the exact type and representative of Stringfellow. The slave-breeders and slave-traders, are a small, odious and detested class, among you; and yet in politics, they dictate the course of all of you, and are as completely your masters, as you are the masters of your own negroes.

You enquire where I now stand. That is a disputed point. I think I am a whig; but others say there are no whigs, and that I am an abolitionist. When I was at Washington I voted for the Wilmot Proviso as good as forty times, and I never heard of any one attempting to unwhig me for that. I now do no more than oppose the extension of slavery.

I am not a Know-Nothing. That is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocracy.

Mary will probably pass a day or two in Louisville in October. My kindest regards to Mrs. Speed. On the leading subject of this letter, I have more of her sympathy than I have of yours.

And yet let [me] say I am Your friend forever

A. LINCOLN—