Contributing Editors for this page include Brenda Klawonn and Sarah Turpin

Ranking

#1 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

Context: There are five versions of the Gettysburg Address in Abraham Lincoln’s handwriting. The so-called “Bliss Copy” was the final one prepared by the president in March 1864 and designed to be lithographed (or copied) for sale at the Baltimore Sanitary Fair in April. Alexander Bliss was one of the Fair’s organizers. The “Bliss Copy” has become the standard text for Lincoln’s November 19, 1863 Gettysburg Address, although it was definitely not the text he used for delivery. The most noticeable difference between the earlier and later copies of the Address was the inclusion of the phrase “under God” in the final sentence, which only appears in the final three copies prepared in February and March 1864. Otherwise, the variations are minor, mostly grammatical. Regardless of the version, however, it is without doubt that Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address offers in a mere ten sentences and only about 272 words the most evocative and powerful explanation for why Northerners had to continue to fight the Civil War despite its terrible human costs. The Bliss Copy is now displayed inside The White House and provides the text for the version at the Lincoln Memorial (By Matthew Pinsker)

“Four score and seven years ago….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, November 19, 1863

The Lincoln Log, November 19, 1863

Image Gallery

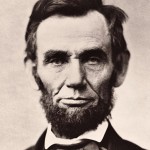

- Abraham Lincoln in 1863

- Lincoln at Gettysburg

- Lincoln at Gettysburg (Detail)

- Hay draft of Gettysburg Address

- Diagram of Soldiers’ National Cemetery

- Gettysburg Parade (Nov. 19)

- Gettysburg Town, 1863

- Bayard Wilkeson

- Sam Wilkeson

- Wilkeson article (with highlights)

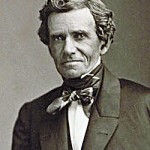

- Daniel Webster

- Lincoln Memorial

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by educator Brenda Klawonn, Understanding Lincoln participant, Fall 2013

Close Reading by Students in Sarah Turpin’s first grade class, Clemson, SC (Posted at YouTube, November 15, 2013)

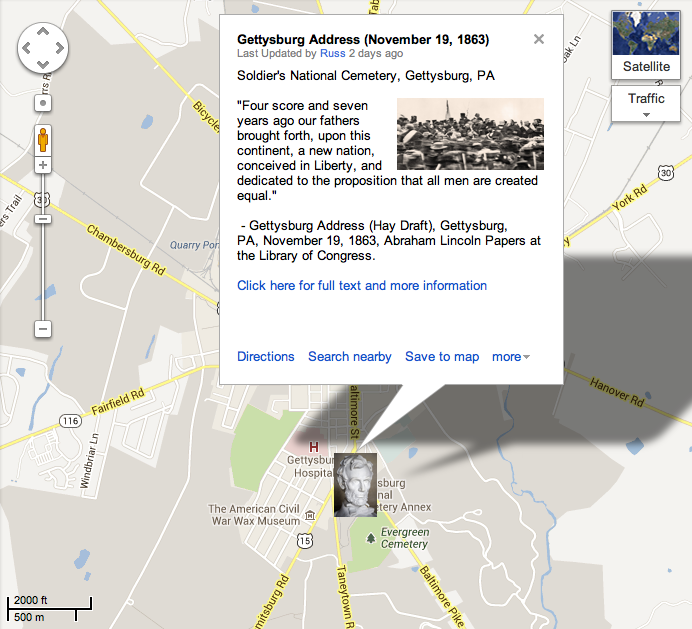

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Nicolay Draft, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

Hay Draft, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

Everett Copy, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

Bancroft Copy, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

Bliss Copy, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863

Daniel Webster, second reply to Robert Hayne, January, 1830

Samuel Wilkeson, “Details From Our Special Correspondent,” New York Times, July 6, 1863

Michael Jacobs letter to Abraham Lincoln, October 24, 1863

David Wills letter to Abraham Lincoln, November 2, 1863

Edward Everett letter to Abraham Lincoln, November 20, 1863

Daily Evening Bulletin, “President Lincoln’s Address at Gettysburg,” December 18, 1863

How Historians Interpret

“When composing his speech, Lincoln doubtless recalled the language of Daniel Webster and Theodore Parker. In Webster’s celebrated 1830 reply to Robert Hayne, the Massachusetts senator referred to the ‘people’s government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people.’ Parker, whom the president admired and who frequently corresponded with Herndon, used a similar definition of democracy. Lincoln was familiar with at least two of Parker’s formulations. In his ‘Sermon on the Dangers which Threaten the Rights of Man in America,’ delivered on July 2, 1854, the Unitarian divine twice referred to ‘government of all, by all, and for all.’ In another sermon delivered four years later, ‘The Effect of Slavery on the American People,’ Parker said ‘Democracy is Direct Self-government, over all the people, for all the people, by all the people.’ Lincoln, who owned copies of these works, told his good friend Jesse W. Fell that he thought highly of Parker. Fell believed that Lincoln’s religious views more closely resembled Parker’s than those of any other theologian. Lincoln may also have recalled the words that Galusha Grow, speaker of the U.S. House, uttered on the memorable 4th of July 1861 as Congress met for the first time during the war: ‘Fourscore years ago fifty-six bold merchants, farmers, lawyers, and mechanics, the representatives of a few feeble colonists, scattered along the Atlantic seaboard, met in convention to found a new empire, based on the inalienable rights of man.’ Many newspapers published that speech.”

“Lincoln read his draft to no one before he reached Gettysburg, and he explained to no one why he had accepted the invitation to attend the dedication ceremonies or what he hoped to accomplish in his address. Yet his text suggested his purpose. When he drafted his Gettysburg speech, he did not know for certain what Edward Everett would say, but he could safely predict that this conservative former Whig would stress the ties of common origin, language, belief, and law shared by Southerners and Northerners and appeal for a speedy restoration of the Union under the Constitution. Everett’s oration could give another push to the movement for a negotiated peace and strengthen the conservative call for a return to ‘the Union as it was,’ with all the constitutional guarantees of state sovereignty, state rights, and even state control over domestic institutions, such as slavery. Lincoln thought it important to anticipate this appeal by building on and extending the argument he had advanced in his letter to Conkling against the possibility of a negotiated peace with the Confederates. In the Gettysburg address he drove home his belief that the United States was not just a political union, but a nation—a word he used five times. Its origins antedated the 1789 Constitution, with its restrictions on the powers of the national government; it stemmed from 1776 . . . In invoking the Declaration now, Lincoln was reminding his listeners—and, beyond them, the thousands who would read his words—that theirs was a nation pledged not merely to constitutional liberty but to human equality. He did not have to mention slavery in his brief address to make the point that the Confederacy did not share these values. Instead, in language that evoked images of generation and birth . . . he stressed the role of the Declaration in the origins of the nation, which had been ‘conceived in Liberty’ and ‘brought forth’ by the attending Founding Fathers. Now the sacrifices of ‘the brave men, living and dead, who struggled here’ on the battlefield at Gettysburg had renewed the power of the Declaration.”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), pp. 461-462

Further Reading

For educators:

- Handout –Gettysburg Revisions (Pinsker)

- Blog Divided, New Details About First Draft (Matthew Pinsker)

- Civil War Trust, Gettysburg Address Lesson Plans (Grades 4-12)

- NEH EDSITEment, Gettysburg Address (Grades 9-12)

- Understanding Lincoln (Prezi), Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (Emily Weiss)

For everyone:

- Gettysburg Address exhibition (Library of Congress)

- The Gettysburg PowerPoint Presentation (Peter Norvig)

- Huston, James L. “The Lost Cause of the North: A Reflection on Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 33 (Winter 2012)

- Johnson, Martin P. “Who Stole the Gettysburg Address?” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 24 (Summer 2003)

Searchable Text

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.