Ranking

#17 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“In pursuance of the sixth section of the act of congress….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, July 22, 1862

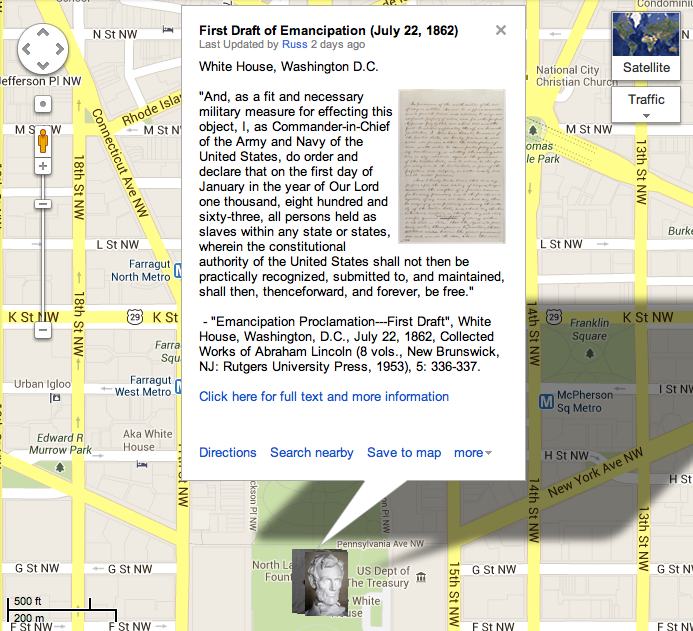

Image Gallery

- Lincoln and Cabinet

- Image of First Draft

- John Hay

- Orville Browning

- Page image of Lincoln’s note

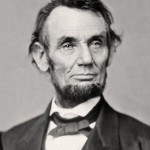

- Lincoln in 1862

- US House of Representatives, 1861

- US Capitol, 1862

- Image of 1864 letter to Hodges

- Lincoln in 1864

- Map of Kentucky

- John Charles Fremont

- Simon Cameron

- David Hunter

-

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: First Draft of Emancipation (1862) from Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

How Historians Interpret

“To justify so momentous a step, Lincoln decided not to appeal to the idealism of the North by denouncing the immorality of slavery. He had already done that eloquently and repeatedly between 1854 and 1860. Instead, he chose to rely on practical and constitutional arguments which he assumed would be more palatable to Democrats and conservative Republicans, especially in the Border States. He knew full well that those elements would object to sudden, uncompensated emancipation, and that many men who were willing to fight for the Union would be reluctant to do so for the liberation of slaves. To minimize their discontent, he would argue that emancipation facilitated the war effort by depriving Confederates of valuable workers. Slaves might not be fighting in the Rebel army, but they grew the food and fiber that nourished and clothed it. If those slaves could be induced to abandon the plantations and head for Union lines, the Confederates’ ability to wage war would be greatly undermined. Military necessity, therefore, required the president to liberate the slaves, but not all of them. Residents of Slave States still loyal to the Union would have to be exempted, as well as those in areas of the Confederacy which the Union army had already pacified. Such restrictions might disappoint Radicals, but Lincoln was less worried about them than he was about Moderates and Conservatives.”

“On July 22 his advisers did not immediately realize that they were present at a historic occasion. The secretaries seemed more interested in discussing Pope’s orders to subsist his troops in hostile territory and schemes for colonizing African-Americans in Central America, and they had trouble focusing when the President read the first draft of his proposed proclamation. The curious structure and awkward phrasing of the document showed that Lincoln was still trying to blend his earlier policy of gradual, compensated emancipation with his new program for immediate abolition. It opened with an announcement that the Second Confiscation Act would go into effect in sixty days unless the Southerners ‘cease participating in, aiding, countenancing, or abetting the existing rebellion.’ The President then pledged to support pecuniary aid to any state—including rebel states—that ‘may voluntarily adopt, gradual abolishment of slavery . . . At the outset of the meeting the President informed the cabinet that he had ‘resolved upon this step, and had not called them together to ask their advice, but to lay the subject-matter of proclamation before them,’ and the discussion that followed was necessarily rather desultory . . . Reluctantly Lincoln put the document aside. Shortly afterward, when Sumner on five successive days pressed the President to issue his proclamation, Lincoln responded, ‘We mustn’t issue it till after a victory.'”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 365-366

Further Reading