Fighting the Fugitive Slave Act: A Movement in Stages

Introduction

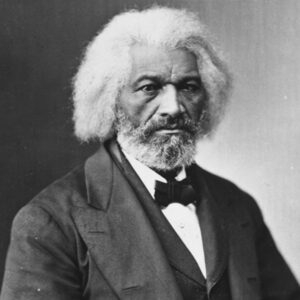

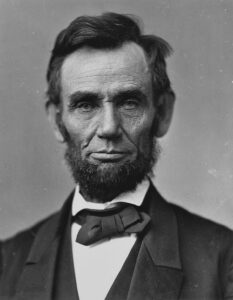

“I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils, but I bite my lip and keep quiet.”[1] This confession by Abraham Lincoln revealed his complex approach to the controversial Fugitive Slave Act. On the one hand, Lincoln loathed slavery, viewing it as a great social evil. Yet on the other, he always vowed to obey the law of the land. But this tricky balancing act made passionate abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass skeptical of Lincoln’s commitment to antislavery. Douglass refused to obey the federal law on runaway slaves and committed to abolishing it as quickly as possible, calling it “the most cruel, unconstitutional, and scandalous outrage of modern times.”[2] If these two men hated slavery as much as their rhetoric suggested, then it appears confusing– and perhaps in Lincoln’s case hypocritical—why their responses were so different. However, their contrasting responses illustrated complementary political interests within their shared movement.

The question was who antislavery forces should have appealed to most to ignite change and when they should have taken action to ensure a positive outcome. Much like today, American politics was a balancing game between when to wait and when to act. If one acted too quickly, they risked losing all their progress. Yet, if one waited too long, they might have missed the only opportunity to make a more perfect union. Lincoln and Douglass shared the same values, but had different priorities in their fight for freedom. Whereas Douglass valued abolishing slavery over all else, Lincoln also wanted to preserve the union. Yet somehow, these profound differences complemented each other.

Background on the Fugitive Slave Act

The Fugitive Slave Act was passed as part of the Compromise of 1850, but its origins trace back to the Constitution. Article 4, Section 2, guaranteed the right of slave owners to reclaim escaped slaves.[3] However, because it was phrased in passive tense, it was unclear who was responsible for enforcing it.[4] The clause’s phrasing was not an accident but rather a reflection of the times. Slavery was already becoming a contested issue when the Constitution was drafted, thus any provision to protect it was likely the product of compromise.

Due to the clause’s ambiguity, it did not take long before another law was passed. In 1793, they passed the first Fugitive Slave Act.[5] This initial act guaranteed slave owner’s rights to recover runaways and deemed it criminal for anyone to be complicit.[6] However, the law did little to deter runaways because it was not always enforced in the north. As the north and south became more contested over the issue of slavery in the coming decades, more fugitive slaves made their exoduses to freedom.[7]

Thus in 1850, the south demanded another Fugitive Slave Act be passed.[8] This Act intensified the penalties outlined in the previous one, denying slaves due process rights, criminalizing housing fugitives, and increasing fines for complicity.[9] The act was undoubtedly controversial, and caught the attention of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln, who both had strong opinions on the issue.

Douglass and Lincoln- Two Antislavery Perspectives on the Fugitive Slave Act

In many ways, Lincoln and Douglass shared the same view on the issue. Lincoln called the obligation to return runaway slaves a “dirty and disagreeable job.”[10] Douglass thought it went against the very principles the United States was founded on. However, an important distinction is that whereas Lincoln hated the law, he still obeyed it, but Douglass did not. In fact, Douglass himself was a runaway slave.

While a slave, Douglass became a committed abolitionist who made it his life’s goal to end slavery, but he realized that to best fight for the cause, he needed to be free. He escaped from slavery on the underground Railroad in Maryland in 1838 and subsequently traveled to New York. There, he learned from William Lloyd Garrison to adopt the mentality that slavery degraded everyone and everything it touched.[11] Over time, Douglass adopted nuanced arguments from Gerrit Smith, who taught him to believe the Constitution was an anti-slavery document. Accordingly, it was the duty of the government to abolish slavery because the Preamble guaranteed the “blessings of liberty” for all men.[12] From then on, he urged all American’s who believed in the United States’ founding principles to fight against slavery. He soon became an active leader in the National Colored Citizens Conventions, where he debated ways to defy the Fugitive Slave Act, assist runaways, and protect northern blacks. Douglass viewed any compromise as threatening to the progress of the antislavery movement.[13] Perhaps this was the reason Douglass was so weary of Abraham Lincoln at first.

Abraham Lincoln took a much less radical approach to the antislavery movement, arguing that to outright abolish slavery would threaten the union’s future.[14] In the early 1850s, Lincoln became a Republican figure who tried to stop the spread of slavery by building an anti-slavery coalition. He hoped that once he achieved this goal, people would see voluntary abolition of slavery as the next logical step. He was worried that the fugitive slave crisis would distract from his end goal because it was scaring away moderates.[15]

Lincoln also viewed the union and the Constitution as inseparable. Since he saw one as contingent on the other, to preserve the union, he had to follow all provisions outlined in the Constitution, including the Fugitive Slave Clause and by extension the Fugitive Slave Act. This approach may appear as though Lincoln prioritized his commitment to the union over his antislavery efforts, but that was not the case. He thought if he tried to accomplish too much at once, he would lose the moderates and the whole antislavery effort would collapse. Though his end goal may have been more radical than he led on, he understood the need to be conservative and patient in his efforts. It is important to note that Lincoln’s fight for freedom occurred at different times and on different platforms than Douglass’s because their priorities were not the same.

Douglass made his grievances known about the Fugitive Slave Act from the beginning. He did so on a public platform in 1852 when he gave his “Fifth of July” speech. In the speech, he called out the hypocrisy of the American people who failed to live up to the values outlined in the Declaration of Independence, saying, “America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future.”[16] Later in the speech, he called out slaveholders who “hunt them with dogs” as morally corrupt.[17]

Only a month later, in his “Fugitive Slave Law” speech, Douglass went even further. He argued that to “command respect” for slaves, words alone were not enough. To show that the Fugitive Slave Act was a dead letter, Douglass advocated to “make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers.”[18] He justified it saying it “is perfectly right as long as the colored man has no protection.”[19] In Douglass’s view, slaves did not have to abide by laws that provided them with no protection or liberty.

Lincoln approached the issue in a much different way. He tried to avoid speaking about it—especially in public—because it was

divisive to antislavery opponents. Though radicals such as Douglass wanted to immediately dismantle the law, Republican moderates felt they were obliged to enforce the clause and the laws out of loyalty to the Constitution. Thus, he kept his sentiment rather private despite loathing it. In his 1855 letter to Joshua Speed, for example, he expressed acknowledgement of his rights and obligations under the Constitution yet described every aspect of slavery as “torment” and said it made him “miserable.”[20] Later in the letter, he explained how northerners had to “crucify their feelings” to maintain loyal to the union.[21]

In other letters written that year, Lincoln spoke of the United States’ failure to uphold the liberty of man, explaining that when they were the “political slaves” of King George and wanted to be free, Americans thought the maxim “all men are created equal” was “a self-evident truth,” but now that they were no longer slaves but masters, they called the same maxim a “self-evident lie.”[22] He understood the hypocrisy of the time, knew it was wrong, and gradually built a coalition of people who believed the same thing.

Conclusion

Today, Douglass and Lincoln’s different approaches to the antislavery movement and Fugitive Slave Act show how difficult it can be to unify people around a political movement. To Douglass and Lincoln, the question of when to fight for freedom was one of opinion, based on the same values but different priorities. For Lincoln, it was about gradual change so that he would not lose the union during his fight for freedom. For Douglass, it was about rapid change so that no one would have to wait any longer to be free.

In modern times, there is still a difference of opinion over the best approach to ignite change. It can be controversial and uncomfortable to talk about — especially when people’s lives are on the line. Sometimes, it can feel like there is a moral hierarchy where the only meaningful action is fast action, or that slowly building a coalition means that one is not as committed to the cause. Lincoln’s approach shows that this is not necessarily the case. Sometimes, fighting for a cause is all about timing. Since people are creatures of habit, it is important to let them adjust to an idea before putting it in full force. Of course, that is hard to accept when people are the constant victims of an unjust system. Douglass’s approach shows that passion might be necessary to bring awareness about inequality. It shows that while some are comfortably adjusting to an idea, other people are dying. However, it is hard to say with confidence whether fast action will yield the intended result. The joint efforts of Lincoln and Douglass show that there are many complex factors that can go into creating change in public opinion, and that sometimes allies can lose track of their different roles and complementary priorities. Their lessons should serve as a reminder that we should not be too quick to judge– good people can fight together from many angles in order to build successful movements.

By: Jordyn Ney

______________________________________________

[1] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007), 64.

[2] “Call for a Colored National Convention,” Frederick Douglass’ Papers (1853). [Accessible Archives].

[3] Andrew Delbanco, The War Before the War (Penguin Press, 2018), 19.

[4] Delbanco, 19.

[5] Matthew Pinsker, “Interpreting the Upper-Ground Railroad,” The Dickinson Survey of American History (2021).

[8] Oakes, 5.

[9] Oakes, 5.

[10] Oakes, 64.

[11] Oakes, 8-9.

[12] Oakes, 18-20.

[13] Oakes, 26.

[14] Oakes, 43.

[16] “Frederick Douglass’s Fifth of July Speech (1852),” excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar hosted by Dickinson College (2021).

[17] “Frederick Douglass’s Fifth…”

[18] “The Fugitive Slave Law, speech to the National Free Soil Convention at Pittsburg, August 11, 1852.” Frederick Douglass’ Papers (1852). [Accessible Archives].

[19] “The Fugitive Slave Law…”

[20] “Lincoln’s Private Letters on Sectional Crisis (1855),” excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar hosted by Dickinson College (2021).

[21] Oakes, 64.