St. Louis MO Mississippi Blätter (Westliche Post), August 26, 1860 (Newspapers.com)

“Ein Sklaven-Stampede” –– German for “A Slave Stampede” –– was the headline in the Westliche Post on August 26, 1860. Among the most influential German-language newspapers in Missouri, the St. Louis-based organ provided its readers with a detailed account of the latest “stampede” of enslaved people from the city. By and large, the Post’s rendering of the escape hewed closely to the timeline of events already circulated by one of the city’s leading English-language organs, the St. Louis News. Five enslaved people––a 60-year-old woman, her two sons, a daughter, and another young woman––had “suddenly disappeared” from the farm of slaveholder Edward Bredell, who was absent visiting the east at the time. But while St. Louis’s English-speaking journalists readily leveled blame at “some Abolitionist,” who must have “induced” the five freedom seekers to escape, the Post struck a different tone. “Of course,” the German paper added with an air of derision, “the ‘abolitionists’ are accused of having seduced the escaped.” [1]

The Post’s remark betrayed some of the critical differences in thought between German-born Missourians and their native-born white counterparts, differences that flared into the open when it came to the subject of slavery. As it were, German emigrants tended to embrace more anti-slavery views, many of them having fled from failed liberal revolutions in Europe during the late 1840s. To be sure, not all Germans arriving in Missouri became abolitionists, and substantial cleavages of conservative emigrants would go on to advocate for more conservative approaches to emancipation and African American recruitment during the Civil War. On the whole, however, it was clear that German-born Missourians were less invested in slavery, with emigrants flocking in large numbers to support the Free Soil wing of the Democratic party, and later the anti-slavery Republican party. [2] Accordingly, the primary source materials they left behind offer important insights –– and different perspectives –– into the struggle over slavery in the Missouri borderland.

As Missouri’s German-speaking population soared during the late 1840s and 1850s, a number of German-language newspapers quickly cropped up. In St. Louis, where many emigrants settled, the two major German-language organs were the Anzeiger des Westens (Free Soil Democratic) and its rival the Deutsche Tribüne (Whig/Free Soil Democratic). By decades’ end, the Westliche Post (Republican) had supplanted the now-defunct Tribune, competing with a number of other religious-specific journals also published in German. [3] Outside of the city, smaller-run German-language papers were also established in Gasconade county and St. Charles. Many of these papers have been digitized and incorporated into databases already examined by this project, including GenealogyBank and Newspapers.com. However, scouring German-language sources invites an array of challenges, especially for researchers not fluent in German. Below readers will find some helpful search tips about how we approached the voluminous archive of German-language newspapers, ranging from search queries to translating sources, as well as a breakdown of relevant results for the group escapes on our project timeline.

SEARCH TIPS

- USE SURNAMES. Often one of the few constants in reporting from English-language sources to their German-language counterparts were the surnames of enslavers. Searching for the surname of a particular slaveholder affected by an escape often generated results.

- COMMON PHRASES. It quickly became apparent that German-language papers in Missouri used several terms when referring to the escapes of enslaved people These included “Entflohen” (German for “Escaped”) and “Sklaven” (German for “slaves”).

TRANSLATION TIPS

- LOOK FOR OCR. Many databases, including both GenealogyBank and Newspapers.com, offer both clipping services (digital image captures) and OCR text (optical character recognition). OCR-produced transcriptions can be rough, but when used in combination with the original image and an online translator, can produce decent results.

- GOOGLE TRANSLATE. While it is not without flaws, GoogleTranslate offers the best way to quickly get a sense of what an article in another language is about. Simply copy and paste the OCR text into GoogleTranslate. For best results, review the OCR text with the original image, and try to correct any obvious errors. Then, let GoogleTranslate do the work, and you should have a transcription which, though by no means perfect, is mostly readable.

COVERAGE OF STAMPEDES IN GERMAN-LANGUAGE NEWSPAPERS

St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens, September 11, 1852

St. Louis MO Anzeiger des Westens, September 11, 1852 (Newspapers.com)

ESCAPED SLAVES. The day before yesterday, Mr. Amadee Valle of this city received the news that 9 of his Negroes, who worked in his mines in St, Genevieve County, escaped and [illegible] across the Illinois river. At Sparta, the citizens made an attempt to arrest them, but the [illegible] escaped to the nearby forest. It is said that whites persuaded to escape and offered the means to do so. After the police were informed of the incident, Lieutenant Woodward and 6 other police officers left for Illinois to [illegible].

St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens, September 15, 1852

St. Louis MO Anzeiger des Westens, September 15, 1852 (Newspapers.com)

SLAVE HUNTING. We reported before one [illegible], [illegible] Lieutenant Woodward in escort from several police officers [illegible] Sparta would have left to collect some fleeing slaves from St. Genevieve County. Police officials leaned back from their unsuccessful expedition last Sunday. It appears that the policemen here had left under the erroneous promise that they had been given by the news, that the Negroes were protected by 2 to 300 people in a church in Sparta. On the way, however, he was already driving them, [illegible] a gentleman who was interested in capturing the slaves and who had traveled ahead, according to rumor that a large division of the St. Louis Police would arrive to arrest the Negroes. The same, of course, would have to be warned: [illegible] flee. Arriving in Sparta, the police officers found a number of people from this State who came there with the same intentions as the police officers. At the same time [illegible] was told that the slaves went to Eden, a [illegible] of Abolitionism, about two miles from Sparta, almost a week earlier. The police officers [illegible] then went to Eden, where they learned that the slaves had already left this place several days before. Regardlss of the [illegible] bay horses and gave themselves all to find the trail of the refugees. …. [illegible] no difficulty [illegible] in Sparta nor in Eden.

St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens, September 22, 1852

St. Louis MO Anzeiger des Westens, September 22, 1852 (Newspapers.com)

Five Negroes, who escaped from this State, were [illegible] the steamer Altona were [illegible] into prison. The [illegible] caught 15 miles behind Alton in the following way: Mr. A.A. Scott, the owner of the Delphi hause in that county happened to be in the house [illegible] when a Negro came to the house [illegible] four of his comrades who were close [illegible] ordered a dinner. Mr. Scott introduced Way to teh fact that a number of [illegible] had fled from St. Genevieve and both are planning a plan to catch them. They asked the Negro to fetch his companions for dinner. While he was gone, they removed all the chairs and what [illegible] could have been used as a weapon from the room. The Negroes came to the table, they had 3 shotguns, which they left in the anteroom. These were thrown up by Scott and Way and the [illegible], the former armed with his own rifle, the latter armed with a knife, into the room, and he asked the Negroes to cross over. This happened and the prisoners were bound here with the altona. The names of the slaves are: Henry, property of Col. Bogy; Isaac, property of Mr. Valee; Edmund, slave of Mr. [Illegible], Joseph, slave of Mr. Jannis; William, slave of Smith. They are all young people with over Edmund who was about [illegible] years old––1 to catch the negroes, the last price of 1000 was immediately paid to the third party. The day before yesterday $200 was caught [illegible] …

St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens, December 1, 1854

St. Louis MO Anzeiger des Westens, December 1, 1854 (Newspapers.com)

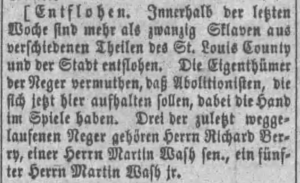

Escaped. Over the past week, more than twenty slaves have escaped from various parts of St. Louis County and the city. The owners of the Negroes suspect that Abolitionists, [illegible] should now be here, have a hand in the process. Three of the last run away, Negroes belong to Mr. Richard Berry, one Mr. Martin Wash sen., A fifth, Mr. Martin Wash jr.

1858 Vernon County Stampede

St. Louis Westliche Post, January 25, 1859

St. Louis MO Westliche Post, January 25, 1859 (Newspapers.com)

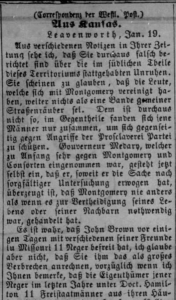

…From Kansas. Leavenworth, Jan. 19. From various notes in your journal, I see that you have been wrongly reported about the unrest that has taken place in the southern part of this territory. They seem to think that the people who have joined Montgomery are nothing more than a gang of muggers. This is by no means the case, on the contrary, those men only came together to protect each other against attacks by the Proslavery Party. Governor Medary, who was initially very antagonistic to Montgomery and Consorten, now admits himself that, insofar as he has carefully examined the matter, he is convinced that Montgomery is never different than when it is to defend a life or its neighbors was necessary, acted… John Brown freed Missouri 11 Negroes a few days ago with several of his friends….

John Doy’s Forgotten 1859 Capture and Rescue

St. Louis Westliche Post, March 3, 1859 (erroneous reporting that abolitionist John Doy and son had been lynched by a pro-slavery mob)

St. Louis MO Westliche Post, March 3, 1859 (Newspapers.com)

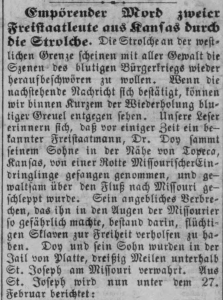

Outrageous murder of two Free Statesmen from Kansas by the thugs. The villains on the western border seem to want to conjure up the scenes of the bloody civil war with all vigor. If the message below is confirmed, we can look forward to the repetition of bloody abominations within a short time. Our readers remember that some time ago a well-known Free State official, Dr. Doy gathers his son near Topeka, Kansas, captured by a group of Missouri intruders, and has been towed to [illegible]… his fearful break, which made him so dangerous in the eyes of the Missouri, was to help fleeing slaves to freedom. Doy and his son were kept in the Jail of Platte, thirty miles below St. Joseph, Missouri. St. Joseph is now reported on February 27th: An express courier arrived here from Platte today, with the news that Doy and his son, near Topeka, Kansas, had arrived a few weeks ago from. Proslavers were drafted new because they were charged with escaping Missouri negroes who had been lynched the night before. The mob is said to have been more than 300 men strong. The iail was stormed and the son was forced to drive the cart up to 2 miles outside the city, where both were hung from a tree. Old Doy pleaded for his life, but the dehumanized gang didn’t hear him. The son was hanged first. In Platte there is great excitement because of these events…. We still want to give up hope that the reports are over, when the worst seems to be the worst from the side of the Gran. But if the news is confirmed, the response from the Free State of Kansas will not be long in coming, and [illegible] who will be avenged.

St. Louis Westliche Post, August 3, 1859

St. Louis MO Westliche Post, August 3, 1859 (Newspapers.com)

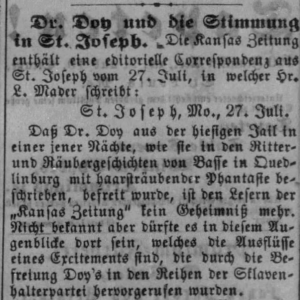

Dr. Doy and the mood in St., Joseph. ‘The Kansas newspaper contains an editorial correspondence from St. Joseph from 2f. July, in which [illegible] St. Joseph, Mo., July 27. That Dr. Doy was freed from the high Jail in one of those nights, as described in the knights and robber stories of [illegible]… with hair-raising imagination, is the readers of [illegible]… But it could be there at that moment, which constitutes the outflows of an excitement caused by the liberation of Doy [illegible] the ranks of the slave keeper party….

1860 St. Louis Stampede

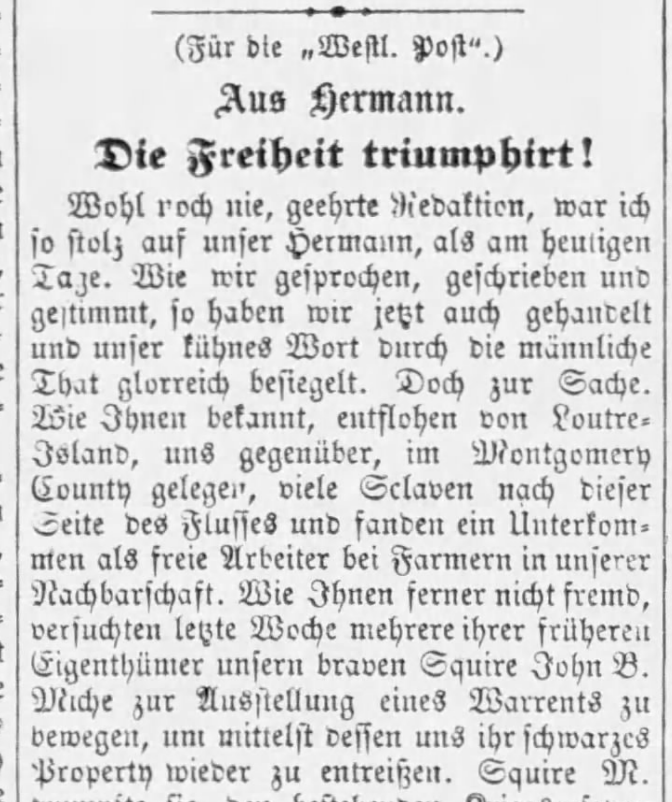

St. Louis Mississippi Blatter [Sunday edition of Westliche Post ], August 26, 1860

A Slave Stampede. Within a few days, five slaves suddenly disappeared [illegible] Edward Bredell [illegible] farm on the Clayton Road, 6 miles from town. The refugees consist of a woman, her two sons and a daughter, resp. 7, 12 and 21. [Illegible] girl who is closely related to the family. One of the sons was his driver and enjoyed his trust. Mr. Bredell is visiting the east and the slaves are under the overseer. The old woman designed the whole escape plan. She asked the overseer for permission to visit a female [child?] that was granted to her. When the slaves were gone, the overseer became suspicious and went to the neighbors’ house. The slaves are all gone and have escaped any [illegible]. Of course, the “abolitionists” are accused of having seduced the escaped. It is not in doubt that Mr. Bredell’s slaves are well treated; years ago he emancipated 30 to 40 slaves in Baltimore, which he would have acquired by inheritance.

St. Louis Westliche Post, December 3, 1862

St. Louis MO Westliche Post, December 3, 1862 (Newspapers.com)

(For the “Westl. Post”.) From Hermann. Freedom triumphs! Probably never [illegible], dear editorial staff, I was so proud of our Hermann [illegible]. As we spoke, wrote and voted, so did we now we have also acted and our bold word has been gloriously sealed by the male act. But to the point. Known to you, escaped from Loutre Island, opposite us, in Montgomery County, many slaves after this side of the [illegible] and found a lodging [illegible] as freelance workers with farmers in our neighborhood, not unfamiliar to you, several of their previous owners tried to convince our good squire John B. Miche to issue a warrant last week, in order to snatch their black property from us M. duly trumped them according to the existing laws of war and his duty as a Republican, and let them go their own way with a fervent and vengeance. Yesterday the gentlemen succeeded [illegible] Negro warrants from a German peace judge, his name is Karl Sandberger, to receive warrants and the deputy sheriff immediately caught four young negroes and put them in the county jail. But now the people rose in fine majesty. The news of this disgrace passed through town and surroundings like wildfire. The brave Germans clustered together, even the [illegible], with a few exceptions, did not fall behind. Curses, threats and curses against the slave owner and her helper, the Sandberger, fulfilled the rust, and the end was assured unanimously that the poor Negroes should be free people by morning, whether by legal means or by storming the jail by bloodshed, no matter. Gasconade County is not supposed to be a slave hunting area and Hermann’s free Germans do not want to be the scold and mockery of the country. [illegible] other equally arrogant but calm-thinking citizens moved excited people to postpone any use of force until at least 9:00 p.m. and asked for their major gene during this. Curtis for employment Capt. C.C.Manwaring as Provost Marshall, since he happened to discover that the previous Marshal [illegible] set up guards at the courthouse (so stood among others the old Strehly brother-in-law of the Blessed Papa [illegible] for hours on end [illegible] in the bitter cold [illegible]… At 9:00 in the evening the men came back with guns and crushing tools and were about to leave for the jail. When the most anticipated dispatch arrived, and the [illegible] immediately found themselves among three thunders in the [illegible] Gen. Curtis issued after the new Provost Marshal Manwaring, which immediately issued an order to release the Negroes. You can imagine the jubilation with which the poor alder was brought out of the singing papa. [Illegible] gave them a good evening meal and some good farmers took them to night quarters. Old Michael Poeschel kept up from the beginning to the end and the best old citizens of the city participated in the fashion that trampled on the law, as local demo friends would like to say. But everything happened according to the military laws recognized by the Congress. So we emancipate -– Hermann is [illegible] ‘Hurray for Union and Freedom! Yours Wm. Wesselhöft. Nov. 26, 1862.

DIGITIZED GERMAN-LANGUAGE NEWSPAPERS BY STATE

Missouri

Anzeiger des Westens (St. Louis, MO) – Free Soil Democratic, Republican (late 1850s – early 1860s), Democratic (post-1863) // Editors Carl Daenzer // Dates available: 1842-1869 (Newspapers.com)

Die Gasconade Zeitung (Hermann, MO) – Dates available: 1860-1922 (GenealogyBank.com)

Hermanner Volksblatt (Hermann, MO) – Dates available: 1860-1922 (Newspaperarchive.com)

Hermanner Wochenblatt (Hermann, MO) – Dates available: 1845-1855, 1860-1871 (Newspapers.com)

Licht-Freund (Hermann, MO) – Dates available: 1843-1845 (Newspapers.com)

St. Charles Demokrat (St. Charles, MO) – Dates available: 1857-1886 (Newspapers.com)

Westliche Post (St. Louis, MO) – Republican // Editors Carl Daenzer, F. Wengel, (Carl Schurz later co-owner) // Dates available: 1857-1958 (Newspapers.com) **Sunday edition called Mississippi Blätter

Illinois

Chicago Illinois Staats-Zeitung – Free Soil Democratic, Republican // Editor George Schneider // Dates available: 1858 (one issue only) (GenealogyBank)

Iowa

Die Wochentliche Demokrat (Davenport, IA) – Dates available: 1862-1865 (Newspapers.com)

Wisconsin

Atlas Tagliche Ausgabe (Milwaukee, WI) – Dates available: 1859-1860 (Newspapers.com)

Banner Und Volksfreund Vereinigt Tagliche Stadt-A (Milwaukee, WI) – Dates available: 1855-1857 (Newspapers.com)

Das Tagliche Banner (Milwaukee, Wi) – Dates available: 1851-1852 (Newspapers.com)

Der Volksfreund (Milwaukee, WI) – Dates available: 1847-1850 (Newspapers.com)

Taglicher Volksfreund (Milwaukee, WI) – Dates available: 1850-1852 (Newspapers.com)

Kansas

Der Deutsche Kreiger (Fort Scott, KS) – Dates available: 1862 (Newspapers.com)

Kansas Zeitung (Atchison, KS) – Dates available: 1857-1858 (Newspapers.com)

Leavenworth Zeitung (Leavenworth, KS) – Dates available: 1858-1859 (Newspapers.com)

[1] “A Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Mississippi Blätter (Sunday edition of Westliche Post), August 26, 1860 (translated using GoogleTranslate); “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis News, quoted in Louisville, KY Daily Journal, August 28, 1860.

[2] Kristen Layne Anderson, Abolitionizing Missouri: German Immigrants and Racial Ideology in Nineteenth-Century America (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2016), introduction and chapter 1. Also see, Kristen Layne Anderson, “German Americans, African Americans, and the Republican Party in St. Louis, 1865-1872,” Journal of American Ethnic History 28:1 (Fall 2008): 34-51.

[3] For a detailed overview of St. Louis’s German-language papers and their shifting political affiliations, see Anderson, Abolitionizing Missouri, esp. introduction.