Fugitive slaves escaping by boat. (House Divided Project)

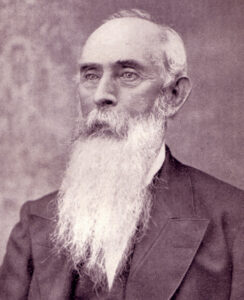

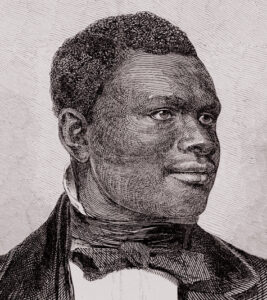

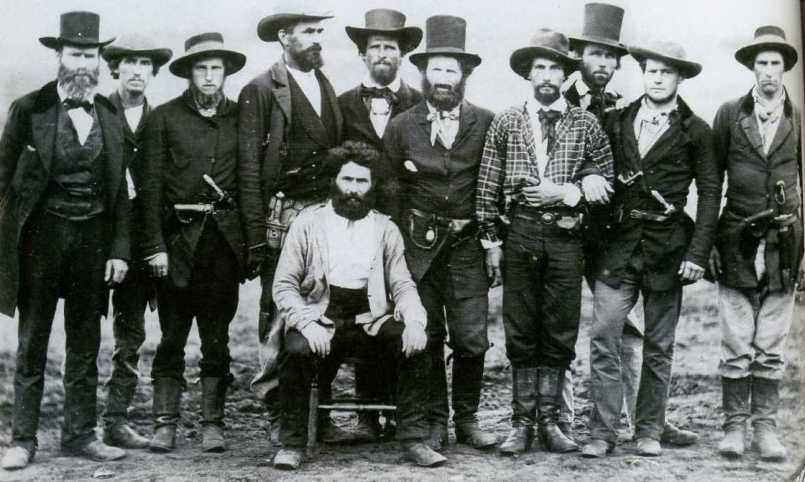

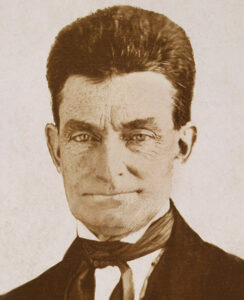

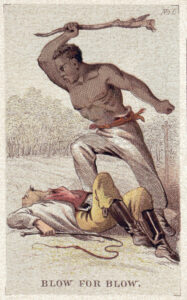

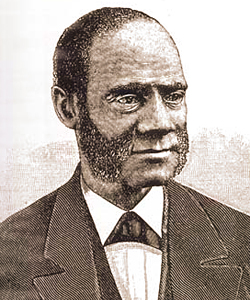

An enslaved man in St. Louis, Missouri, William Wells Brown was filled “with the most intense anxiety” as he plotted his escape across the Mississippi River. Late one evening in 1833, Brown and his mother finally executed their plan, and riding a small skiff on a “very swift” current, the mother and son duo were “soon upon the Illinois shore.” Their taste of freedom was brief, however, and they were soon manacled by slave catchers and returned to bondage in Missouri. Yet in January 1834, Brown at last succeeded, smuggling himself on board a steamboat bound for Ohio. [1]

After escaping from slavery in St. Louis, William Wells Brown became a prominent figure in the anti-slavery movement. (House Divided Project)

Brown’s story is one of many profiled in Cheryl LaRoche’s book, The Geography of Resistance (2013). For years prior to his escape, Brown had worked on steamboats that canvassed the Mississippi River, gaining an intimate familiarity with the surrounding region. That he and his mother landed near the abolitionist stronghold of Alton, Illinois, was no accident, maintains LaRoche. Not only was Alton filled with anti-slavery sympathizers, but just miles away was a crucial, although often overlooked free African American settlement, known as Rocky Fork.

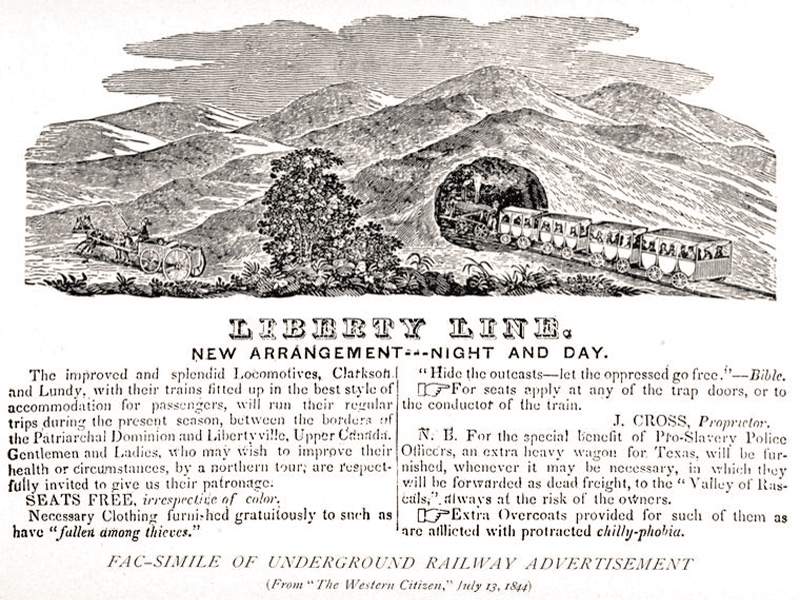

Rocky Fork is one of four African American communities along the North-South border that LaRoche profiles in her book. Of these four settlements (Rocky Fork and Miller Grove in southern Illinois, Lick Creek in Indiana, and Poke Patch in southern Ohio), just Rocky Fork survives today. With few written sources available, LaRoche taps into archaeological evidence, oral histories and geographical analysis (“using the land as a type of document”), to produce an account of what she terms “the geography of resistance.” What emerges is a portrait of African Americans, on both sides of the border, acting as central agents in determining their own fates. Most freedom seekers, LaRoche notes, “negotiated either all or the most difficult or dangerous portion of the trip alone or with the help of other Blacks.” Quakers and other white abolitionists, she writes, while playing important roles, also harbored “ambivalent sentiments” towards African Americans, and were not the driving force behind the resistance to bondage. In LaRoche’s view, geography bears this out. Many well-known Underground Railroad sites “operated within a two- to three-mile radius of small Black enclaves.” Documenting these often-overlooked black hamlets, LaRoche maintains, “visually clarifies and exposes the relationships between African American churches, settlements, and historic Underground Railroad routes.” [2]

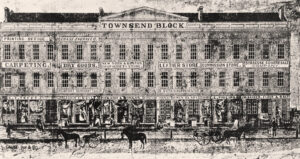

Missouri escapes figure prominently in LaRoche’s book, largely due to her first case study, Rocky Fork. A black settlement situated mere miles from the Missouri border, LaRoche notes that Rocky Fork was “ideally located, remote and not easily accessed.” The larger and better-known abolitionist community of Alton lay just three miles away. Difficult to reach by land, Rocky Fork was instead “highly accessible” by water, via the Mississippi River. Missouri fugitives could follow the river north to Piasa Creek, where two islands enabled them to swim or boat across to Rocky Fork Creek. The small settlement (at its peak counting 45 families) provided “a secluded, safe refuge” for Missouri fugitives, who by the 1830s were arriving with increasing regularity. Escaped slaves, LaRoche writes, enjoyed the advantages of rural living, often setting up house in remote, wooded areas, which “helped discourage pursuers,” who feared for their own safety venturing into the unknown wilderness. [3]

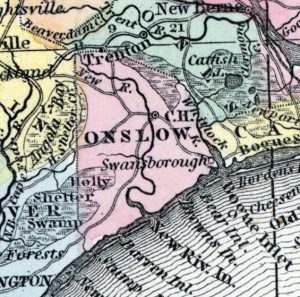

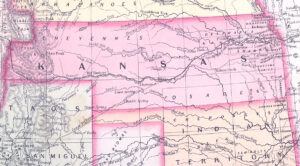

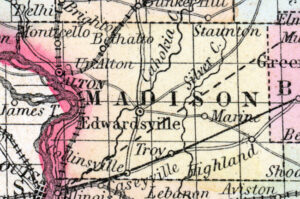

An 1857 map showing the abolitionist stronghold of Alton, Illinois (left center), a short distance upriver from St. Louis. Not specified is the free black community of Rocky Fork, located just three miles west of Alton. (House Divided Project)

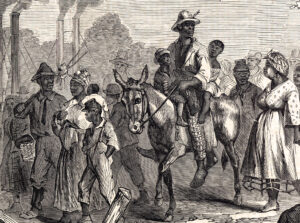

LaRoche does not use the term slave stampede, but she does identify and discuss multiple “group escapes,” including many from eastern Missouri into Illinois. She posits that “as the slavery crisis deepened, the mechanisms of escape extended from lonely singular escapes to groups and families attempting to free themselves from bondage.” These larger escapes, LaRoche argues, turned increasingly violent and eventually gave way to “armed conflict in the name of freedom.” One of the earliest potential stampedes may have been the work of “Mother” Priscilla Baltimore, a former slave who resided in Brooklyn, Illinois, an historically black enclave located across the river from St. Louis. In 1829, Baltimore reportedly led 11 Missouri families (including both free and enslaved persons) across the Mississippi to freedom. Later, a “series of group escapes in 1845,” LaRoche notes, caused considerable consternation among Missouri slaveholders, who seethed that abolitionists had enticed their slaves to escape. Yet another potential stampede dates from 1854, when a free black coachman from Alton concealed 15 Missouri slaves in his carriage. He helped them cross the Mississippi in skiffs, and then sent them on to Chicago. [4]

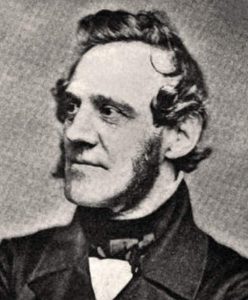

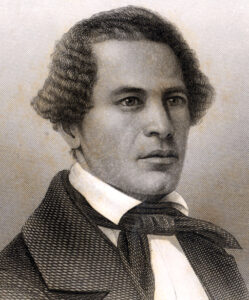

As a child, Henry Highland Garnet escaped slavery in a potential slave stampede. (House Divided Project)

Accounts of other potential stampedes abound throughout the book. Josiah Henson escaped from slavery in Kentucky, traveling to Indiana and eventually Canada, but returned to help lead 30 Bourbon County, Kentucky slaves to freedom. Years later, during the Civil War, eight Kentucky slaves followed in Henson’s footsteps, escaping northward into Indiana. One was recaptured, but the remaining seven managed to reach freedom and enlist in the 28th U.S. Colored Troops. LaRoche also discusses potential stampedes from the eastern slaveholding states. One involved the noted black abolitionist and preacher Henry Highland Garnet, who escaped slavery as a child in 1824, along with 10 enslaved relatives. The group left New Market, Maryland, and reached the Delaware home of Quaker abolitionist Thomas Garrett, and from there moved on to upstate New York. Another potential stampede dates from 1847, when 13 freedom seekers headed north from Williamsport, Maryland, after learning of their impending sale. Just across the border in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, the fugitives linked up with a black operative, George Cole, who guided them to the small town of Boiling Springs, where they briefly stayed at the home of white abolitionist Daniel Kaufman. While the fugitives were ushered off to safety, the Pennsylvania abolitionist was later convicted of aiding their escape. [5]

In terms of this project, The Geography of Resistance adds valuable insight to our understanding of slave stampedes. In discussing group escapes, LaRoche highlights the often neglected roles played by free African Americans living along the North-South border. Over the span of several decades, free black residents of Rocky Fork, Illinois, assisted large groups of enslaved Missourians in their attempts to escape bondage. As we continue our research into slave stampedes, LaRoche’s work reminds us that the border’s free black communities were not simply remote or isolated enclaves, but also potential paths to freedom for groups of escaping slaves.

[1] William Wells Brown, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1847), 67-70, [WEB]; Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, Free Black Communities and the Underground Railroad: The Geography of Resistance (Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 36.

[2] LaRoche, 15, 37, 40-41, 70, 85, 87-88, 101-102, 140.

[3] LaRoche, 22-24, 33-34, 37.

[4] LaRoche, 30, 33-36, 157.

[5] LaRoche, 66-68, 97, 128.