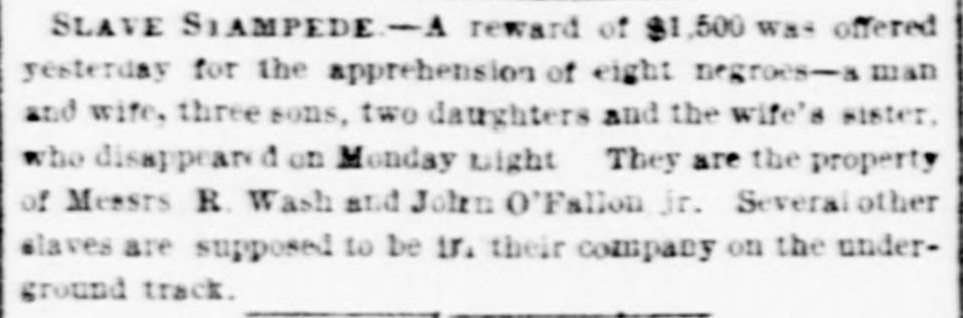

“Slave Stampede,” Daily Missouri Republican, July 16, 1856, p. 3 Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri.

On July 16, 1856, the Daily Missouri Republican reported on a large reward being offered to help recapture a group freedom seekers: “Slave Stampede: A reward of $1,500 was offered yesterday for the apprehension of eight negroes-a man and wife, three sons, two daughters and the wife’s sister, who disappeared on Monday night. They are the property of Messrs R. Wash and John O’Fallon Jr. Several other slaves are supposed to be in their company on the underground track.”[1] This short article, located in the middle of four pages of local and national news, described a group escape of eight or more enslaved blacks as a “stampede.” Yet what does the term mean in this context? Was it meant to sensationalize the news to grab readers’ attention? Or was it designed as a way to dehumanize enslaved people by comparing them to a hoard of wild animals?

Lea VanderVelde, a noted legal historian from the University of Iowa School of Law, attempts to answer these questions and many others in two recent books, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier (2009) and Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom Before Dred Scott (2014). The former is a biography of Harriet Scott that examines her life as a slave and as an often-overlooked plaintiff behind the infamous Scott v Sandford decision. The latter study is a review of around 300 original court case files for freedom suits from the circuit courts of St. Louis, Missouri. All of these cases, described by the author as “songs of freedom,” can be viewed online here.[2] Most of these suits involved claims of enslaved people being held illegally in bondage in either free territories or states, often by slaveholders, such as army officers (in the case of the Scott family) who traveled widely. In both studies, VanderVelde reveals valuable information not only about the nature of freedom suits, but also about the dynamics of group slave escapes in 19th century Missouri.

For example, VanderVelde mentions the July 1856 stampede of eight in a footnote to Redemption Songs (2014) as way to help elaborate on her use of the term “stampede.”[3] In the text, she writes that “As slaves, petitioners are described by witnesses in a passive voice as having the characteristics of objects…They are stolen, even ‘stampeded,’ by third parties.”[4] In her work, VanderVelde always emphasizes the agency of the enslaved, but here she seems to suggest that the term “stampede” was used by their oppressors as a way to dehumanize them.

The term “stampede” surfaces in Mrs. Dred Scott (2009) as well, during an exploration of the ramifications of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. VanderVelde writes, “for the first time [after September 1850], the newspapers noted the new phenomenon of slaves running away in groups. They initially referred to these departures as ‘slave stampedes’ as if the escapees were witless horses.”[5] Yet such group escapes, or “stampedes,” caused slaveholders great anxiety, because as VanderVelde notes, “this sort of exodus suggests [to them] some prior planning and outside assistance to avoid detection.”[6]

One exceptional case, the freedom suits of Milton Duty’s 26 slaves, reveals that the concept of “stampedes” might also be applied to the freedom suit process. During his lifetime, Mississippi slaveholder Duty had ensured the manumission of his slaves by moving them to Missouri (with more liberal manumission policies). They lived together for a year in Missouri, where Duty instructed the slaves to rent out their labor in St. Louis in order to start saving money for their new lives free after bondage. When Duty died in 1838, greedy stakeholders, including both creditors and the executor of Duty’s will, immediately went through Duty’s personal items, tearing up and destroying as much evidence of Duty’s intention to free his slaves as possible. Over the following decade, Duty’s slaves were forced to enter a bitter legal battle to seek their freedom. More than two dozen of them filed for freedom at the same time in St. Louis Circuit Court in 1842. Yet despite the clarity of Duty’s intentions as outlined in his will, and after years of legal struggle, only one of the twenty six slaves was eventually granted freedom. Jesse, the drayman, won his case based in part on his ownership of Duty’s horses. By the time the petition was officially rejected by the Missouri Supreme Court in 1846, several of the original slaves who filed had already died. The story of Duty’s slaves reveals the struggles and obstacles faced by enslaved folks who chose to fight for their freedom legally rather than escaping.[7]

VanderVelde’s work also suggests that whether escaping or petitioning, an important element of enslaved agency was about gender and family. In Redemption Songs (2014), she writes that far more women than men filed for freedom in court. “Most St. Louis freedom suits were initiated by women,” she observes, “Filing suit kept mothers and children together.”[8] Legally, the status of slavery was passed through the mother to children. If the mother’s status changed from enslaved to free, then her children would also become free. This meant that enslaved women had much more incentive than men to take the effort to legally change their status rather than risk family separation in escape. This concept that “men run, [and] women sue” reveals a specific way in which gender, race, and conceptions about motherhood intersected to create unique experiences for enslaved women, and explains one reason why some slaves chose to sue for their freedom.[9]

Freedom suits, much more than escapes, “preserved the status quo.”[10] Many successful petitioners didn’t move away even after winning their cases. Winny, an enslaved woman who won her case, spent the rest of her days in freedom as a washerwoman in St. Louis.[11] Dred and Harriet Scott, who eventually achieved freedom through manumission, also continued their free lives in St. Louis, where Dred worked as a doorman at Barnum’s Hotel.[12]

A statue of Harriet and Dred Scott outside the St. Louis courthouse where they first filed for freedom in 1846 (Dred Scott Heritage Foundation)

A second likely reason that some eligible slaves chose to sue for freedom over escaping was the simple fact that until the Scott case (Scott v. Emerson in the Missouri Supreme Court in 1852 and then Scott v. Sandford in the US Supreme Court in 1857), slaves had a genuine chance at freedom through legal means. In the years leading up to the final Dred Scott decision, St. Louis courts had set a precedent that often surprisingly favored the petitioner in freedom suits. In 1824, this Missouri statue established that if a court reached a “judgment of liberation,” for a petitioner, then that individual was deemed wholly free, even if that judgment directly opposed the wishes of the slaveholder. Of the 300 original court filings from St. Louis that VanderVelde examined, over 100 litigants were granted their freedom.[13]

Still, slaves took on great risk to their lives and livelihoods by making any type of bid for freedom in a system that tried to strip them of their humanity. Both freedom suits and escapes were dangerous acts of bravery that undermined the institution of slavery. They were especially so, because as VanderVelde writes, “survival is a much more significant objective in influencing human behavior than attaining freedom.”[14] What we hope to uncover, however, is how a family of eight, running away together on a July evening in 1856, might have seen their “stampede” as both an act of personal and political survival.

[1] “Slave Stampede,” Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, MO), July 16, 1856. [WEB]

[2] Lea VanderVelde, Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom Before Dred Scott (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 22.

[3] VanderVelde, 263n.

[4] VanderVelde, 203.

[5] Lea VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 287.

[6] VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott, 287.

[7] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 159-176.

[8] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 195.

[9] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 195.

[10] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 195.

[11] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 65.

[12] VanderVelde, Mrs. Dred Scott, 322.

[13] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 20.

[14] VanderVelde, Redemption Songs, 194.