PRINTABLE NARRATIVE

DATELINE: LURAY, MISSOURI, JUNE 2, 1848

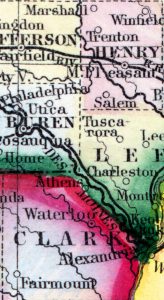

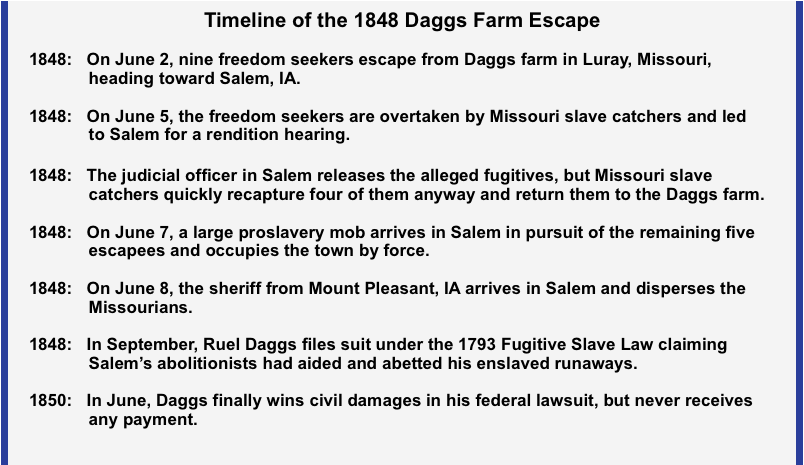

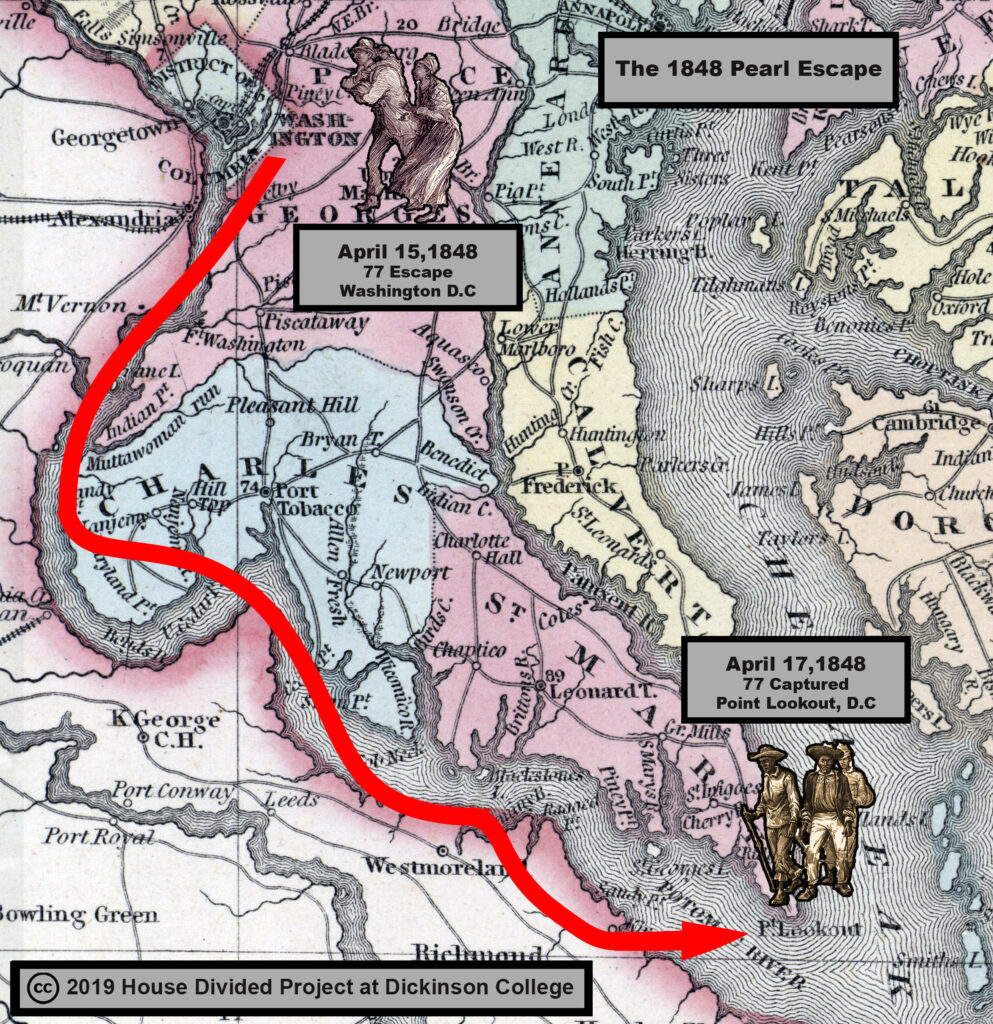

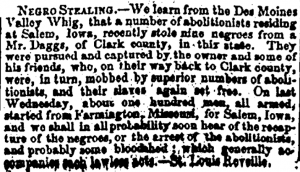

Missouri and Iowa border between Daggs Farm and Salem (Mitchell’s Atlas, 1866)

On the evening of June 2, 1848, a group of nine enslaved people fled from a farm owned by Ruel J. Daggs of Luray, Clark County, Missouri. The group included John and Mary Walker, their four children, along with Sam and Dorcas Fulcher, and their 18-year-old pregnant daughter, Julia. The two families were able to cross the border to the free territory of Salem, Iowa, where an antislavery community stood vigilant in order to protect the freedom seekers from what they considered to be an unlawful rendition. But it was there in Salem where 48 hours later a posse of slave catchers hired by Daggs discovered them, as one eyewitness described, “in a thicket of hazel brush.” At gunpoint, the slave catchers demanded that the freedom seekers give themselves up.[1] Before the standoff became fatal, however, 19 people of Salem were able to bring calm to the “chaotic [and] highly emotional,” scene, according to historian Lowell J. Soike. The Salem residents offered a compromise by suggesting that the alleged freedom seekers slaves be brought before an impartial justice of the peace. The slave catchers yielded. A few hours later, the judicial officer ruled that the Daggs’ posse had presented no evidence proving that the Walker and Fulcher families were legally enslaved. Moments later, in the midst of the abolitionist celebration, and in defiance of the court’s ruling, Daggs’ slave catchers seized four of the runaways–two Walker children along with Dorcas and Julia Fulcher–and rode out of town.

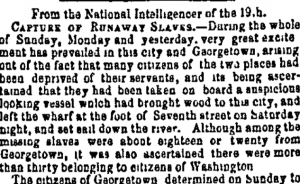

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

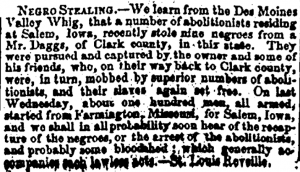

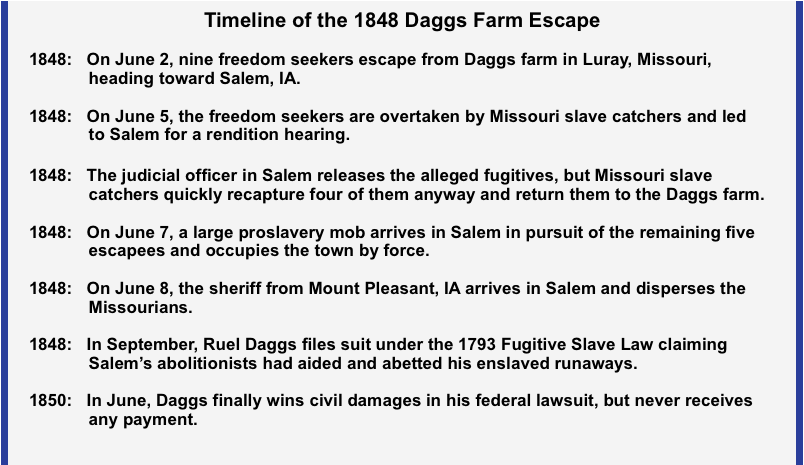

St. Louis Reveille, quoted in New York Evening Post, June 21, 1848 (GenealogyBank)

Newspapers were quick to cover the dramatic confrontation in Iowa across the Missouri border, but none seem to have employed the term “stampede” to describe an organized escape of nine people. However, the absence of the term in this instance should come as no surprise. It was only about a year before, in 1847, that newspapers anywhere in the country had begun to apply the term stampede to larger group slave escapes.[2] Though none of the local or regional newspapers articles covering the escape from the Daggs farm in June 1848 used the term “stampede,” this episode was without doubt one of the most important cases of mass escape in the history of the Underground Railroad. It involved a series of dramatic confrontations, both violent and legal, ultimately contributing to the collapse the federal fugitive slave code from 1793.

MAIN NARRATIVE

The slave state of Missouri possessed a unique slaveholding population. Census records indicate that 88 percent of Missouri slaveholders held fewer than 20 men and women in bondage (the standard threshold for plantations).[3] Born in Delaware in 1775 but raised in Rockingham County Virginia, Ruel Daggs, the son of wealthy landowners Angus and Lydia Daggs, was one of those slaveholders who was a slaveholder without being a stereotypical southern planter. Having first arrived in Luray in 1835 with six enslaved persons, by the late 1840s, Daggs became the slaveholder of 16 people on his 160-acre farm near the Wyaconda River in Clark County, near Missouri’s northern border with Iowa.[4] According to local historian O. A. Garretson, Daggs grew concerned about the “spirit of liberty” that had prevailed in the West. So by 1848, Daggs had “realized the difficulty of holding slaves so near the free State of Iowa,” believed Garretson, and therefore inquired about “selling his slaves south.”[5]

Hearing he and his family would be sold south and in all likelihood that his wife and children would be separated, John Walker, age 22 or 23, escaped from Daggs’s farm alone in May 1848 to ascertain the means to free his entire family. During his initial escape, Walker traveled north into the woods near the Des Moines River, where he arranged a family escape strategy with white resident Dick Leggens (or Liggon) and, according to Garretson, a free African American named Sam Webster.[6] Then, after crossing the river into Iowa, Walker established relations with a group of known abolitionists in the small Henry County township of Salem, located about 15 miles from the Missouri border.

With a population of about 500 residents, Salem was among the first Quaker communities established in the Hawkeye State. The small towns of Salem, Denmark and Washington Village, were, according to Soike, “the core antislavery communities in southeast Iowa.”[7] To Missourians and other pro-slavery communities, Salem certainly appeared to be a hotbed for antislavery activists willing to venture into slave states to “steal” those kept in bondage. But to Aaron Street Jr., a Quaker, Salem abolitionists weren’t raiders; rather, Street Jr. testified, the objective of the antislavery community in Salem was to help freedom seekers who were already “on their way to a land of freedom.” He explained, “we believed it right to take them in and feed them, and give them such directions and assistance, as we ourselves would wish bestowed on us, were we in their situation.”[8] Writing in The Quakers of Iowa, Louis T. Jones described Salem as a place where the children deliberately ignored “this solemn business” while the adults spoke “vague but [in] well understood terms” about the Underground Railroad.[9] John Walker, the freedom seeker from Daggs’s farm, quickly established an alliance with Salem’s leading abolitionists: Street Jr., Thomas Clarkson Frazier, Elihu Frazier, Paul Way, John H. Pickering, William Johnson, John Comer, and Henderson Lewelling.

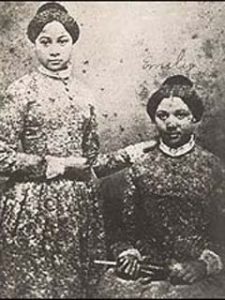

Once finalizing an escape plan that included a safe house on the Missouri side of the Des Moines River and with a network of abolitionists from Salem who would help with transportation, Walker returned to the Daggs farm on June 2, 1848 to take his family to freedom. During the escape, three members of the Fulcher family joined the Walkers. The group, now numbering nine, was made up of Walker, his wife, Mary; their four children, Martha, age 10, William, age 6; George, about age 4, Armistead Poston, about age 1; Sam Fulcher, age 40 or 45, who labored as a tanner, shoemaker, and cooper that had the ability to write and keep accounts; his wife, Dorcas, age 38, who was known as a cook and a weaver, and pregnant daughter, Julia, age 18 or 19, who was also a cook. John Walker and Sam Fulcher were estimated to be worth $900 to $1200, respectively. Mary Walker, Dorcas, and Julia were each worth $600 to $700. Martha was valued up to $300; while William, George and Armistead were $200.[10]

That first night, the Walker and Fulcher families made it as far as Leggens’s remote farmstead before stopping for the night. At dawn a heavy downpour began, which delayed the escape party a day from continuing on their journey. During the wait, everyone remained festive as Sam Webster entertained the freedom seekers with his violin.[11]

Enslaved family fleeing in rain (from William Still’s The Underground Railroad, 1872)

After the rain subsided, Leggens and Webster escorted the two families to a point along the Des Moines River that looked at the shoreline of Farmington, Iowa. Since the current had become “so swollen,” according to Garretson, due to the heavy rains, the two families with the help of their co-conspirators built a raft strong enough to cross the river into Iowa. Jonathan Frazier, a son of Quaker preacher and abolitionist Thomas Frazier, then met the freedom seekers in Farmington. Frazier hid the Walkers and Fulchers in a covered wagon and escorted the runaways during the remaining 20 miles north to Salem.[12] One witness said Salem abolitionist John H. Pickering owned the horses that were hitched to Frazier’s wagon.[13] In a U.S. District Court hearing on the case two years later, Pickering denied that it was his horses used to transport the freedom seekers. His brother, Jonathan Pickering, a proslavery conservative, told a different story, however. He accused his brother, John H. of transporting and harboring the freedom seekers, stating to authorities when he had confronted his brother about the runaways: “[John H.] sniggered in his sleeve and seemed to know where they were.”[14]

It was Monday, June 5, when Frazier picked up the freedom seekers. During the time leading up to that day, Ruel Daggs had tasked his sons, William Rodney, age 36, and George, age 31, with organizing a posse from their neighborhood to pursue the nine freedom seekers across state lines.[15] The Daggs’ eventually enlisted the help of four people: their neighbor James McClure, a man from Farmington named Samuel Slaughter, and upon entering Iowa, McClure and Slaughter also employed the help of two men from Salem, Henry Brown, who knew Ruel Daggs, and Jesse Cook. On the morning of June 5, the four men discovered wagon tracks in the mud. They followed the tracks in the direction of Salem, where they spotted the wagon about a mile in the distance. They gave chase; eventually arriving upon the wagon, now empty and idle, outside the home of Thomas Frazier. After 24 hours spent combing Salem for the runaways, McClure and Slaughter returned to the original spot where they first noticed the wagon tracks while Brown and Cook lagged behind. They soon spotted all nine runaways in the underbrush near the wagon. Brown and Cook then arrived on the scene to help secure the Walkers and Fulchers.[16]

Concerned about her four children, Mary Walker was the first to turn herself over to the slave catchers. Likewise, both Sam and Dorcas Fulcher soon relinquished their freedom. And the pregnant 18-year-old Julia Fulcher also submitted to the captors. Only John Walker refused to be taken. His attempt to preserve his freedom failed, however, as he was subdued by the slave catchers and tied to a post. Slaughter was left in charge of supervising the nine captives while McClure traveled back into Salem to find willing men who could assist in the safe return of the runaways to Daggs.

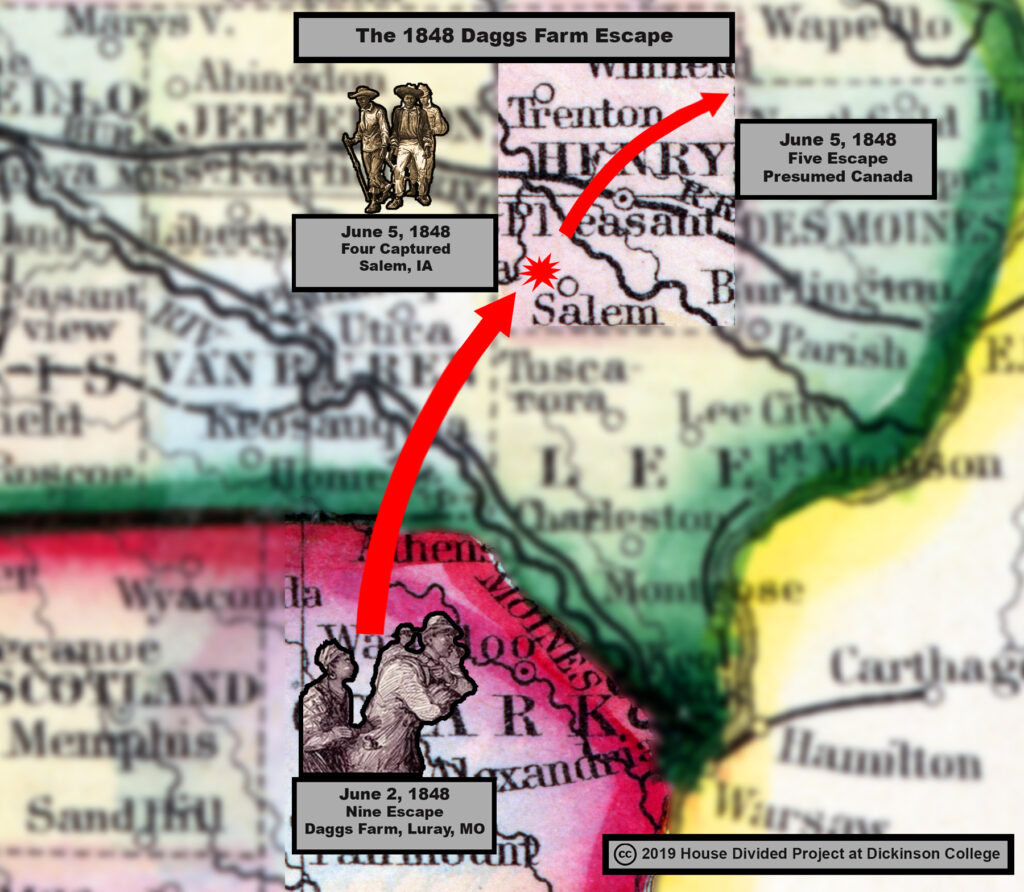

The Henderson Lewelling House, Salem, IA. (National Park Service)

The delay enabled Salem abolitionists to organize an effort to rescue the nine freedom seekers. There is ongoing debate over the crowd size that surrounded Daggs’s posse. While most historical accounts estimate between 50 and 100 Salem residents gathered to free the Walkers and Fulchers, historian Robert Dykstra claims it was only “a dozen local men,” which included Thomas Clarkson Frazier, his brother Elihu Frazier, Moses Pervis, and William Johnson, “who appeared intent on keeping the captives from being carried off.”[17] Meanwhile, the press coverage of the incident reported that Slaughter, Brown, and Cook were “mobbed” by a large group of abolitionists.[18] The Frazier brothers stepped forward to negotiation with the slave catchers. Elihu threatened Daggs’s men that he would “wade in Missouri blood before the negroes should be taken.”[19] Thomas Clarkson offered a solemn alternative by suggesting Salem’s Justice of the Peace Nelson Gibbs adjudicate the case. To circumvent a physical disturbance, the slave catchers acquiesced to the suggestion of a legal hearing.

Word spread throughout Salem at a rapid speed, which resulted in the gathering of a large crowd around Gibbs’ office in what is now known as the Henderson Lewelling House. The crowd was so large, in fact, that John and Mary Walker were able to sneak away from Slaughter with their oldest child, Martha. That left three Walker children and the Fulcher family to undergo a deposition by Judge Gibbs, an antislavery sympathizer whose office in the Henderson Lewelling House would eventually be listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the National Park Service Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. Amid the commotion, Salem’s schoolmaster, Rueben Dorland, stood on a pile of lumber to “harangued the crowd,” wrote historian Louis T. Jones, in an apparent gesture to bring calm to the scene and advocate that the freedom seekers must be taken before the judge.[20] The justice’s office was too small for the large crowd that had amassed so the dueling sides agreed to hold the hearing inside the Friends’ Meeting House, which was commonly used as the venue for abolition meetings, located across the street.

Two Salem Quakers (Aaron Street, Jr. and Albert Button) served as counsel for the alleged runaways. A trained attorney, Button quoted from the Revised Statutes of the Territory of Iowa (1843) explaining that kidnapping of African Americans was unlawful because of personal liberty statutes in Iowa: “If any person or persons shall forcibly steal, take, or arrest any man, woman or child in this Territory. . . ,” he recited, “with a design to take him or her out of this Territory without having legally established his, her or their claim according to the laws of this Territory, or of the United States, shall upon conviction thereof, be punished by a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars and by imprisonment in the penitentiary at hard labor not exceeding ten years.”[21] The slavecatchers, McClure and Slaughter, did not try to argue that point, by invoking the 1842 precedent from the United States Supreme Court (Prigg v. Pennsylvania) which might have easily challenged Button’s interpretation of Iowa’s “state rights.” They either did not know about the law or perhaps chose to ignore the point.

Regardless, Judge Gibbs ruled that McClure and his men did not offer enough evidence proving they were agents working for claimant Ruel Daggs. Gibbs, whose home contained three secret rooms for freedom seekers, also stated that since the alleged runaways had not been brought properly before him, he had no right to adjudicate the matter. He therefore concluded that the Walkers and Fulchers were “free as himself for all he knew.”[22]

Despite Gibbs’s ruling, there was a fight for the remaining alleged freedom seekers outside the Friends’ Meeting House. One of the slave catchers, Henry Brown, shouted at Sam Fulcher, “I’ll shoot that damned son-of-a-bitch.” The crowd prevented Brown from doing harm to anyone. In that instant, however, John H. Pickering led Fulcher, who was taking care of 6-year-old William Walker to Paul Way, an antislavery man described later by a witness at the trial as “an old man clothed in the working garb of the pioneer, with long chin whiskers and wore a pointed topped, lopped down felt hat.” Way delivered a horse to Fulcher and the Walker boy to use for a swift getaway. The others, however, were not so lucky. McClure and Slaughter seized Dorcas and Julia Fulcher and the two remaining Walker children, George and Armistead Poston.[23] The four were returned to Daggs’s farm by force.

Two days later, on June 7, a proslavery mob of angry Missourians estimated by multiple sources to range in size from 100 to 300 and “armed to the teeth,” according to Louis T. Jones, paid a return visit to the Quakers in Salem. Apparently, Daggs had issued a $500 reward for the return of his five at-large runaways. According to witness Rachel Kellum, the group from Missouri now brought with them rifles, pistols, knives, and a canon in order to occupy (and intimidate) the town. Though some conservative Salem citizens testified later that most of the Missourians behaved with “civility,” the slave catchers certainly laid siege to the community. Roadblocks were placed at every exit and  vigilantes were stationed as guards throughout the town. One eyewitness said members of the mob “snapped a pistol at an old crippled man.”[24] Houses were illegally searched, including the residence of Paul Way, who was able to prevent members of the Missouri mob from finding a freedom seeker in his home by threatening to shoot anyone who tried to climb into his attic.[25] The mob also paid a visit to the home of Thomas Clarkson Frazier, whom Jones later described as “the most vigorous abolitionist in the settlement.” Frazier was in fact hiding some of the runaways. Upon hearing the gang was headed to his property, Frazier helped the freedom seekers relocate to a nearby forest. By the following morning Frazier and several of his co-conspirators, Elihu Frazier, John Pickering, John Comer, and at least five more of Salem’s leading residents were being held under duress at a hotel.[26]

vigilantes were stationed as guards throughout the town. One eyewitness said members of the mob “snapped a pistol at an old crippled man.”[24] Houses were illegally searched, including the residence of Paul Way, who was able to prevent members of the Missouri mob from finding a freedom seeker in his home by threatening to shoot anyone who tried to climb into his attic.[25] The mob also paid a visit to the home of Thomas Clarkson Frazier, whom Jones later described as “the most vigorous abolitionist in the settlement.” Frazier was in fact hiding some of the runaways. Upon hearing the gang was headed to his property, Frazier helped the freedom seekers relocate to a nearby forest. By the following morning Frazier and several of his co-conspirators, Elihu Frazier, John Pickering, John Comer, and at least five more of Salem’s leading residents were being held under duress at a hotel.[26]

During the assault, two Salem residents were able to “slip out of town,” writes Soike, to obtain help from a sheriff in nearby Mount Pleasant and to recruit abolitionists from the town of Denmark. Though originally from Virginia, the Mount Pleasant sheriff arrived in Salem on the morning of June 8, intending to help his fellow Iowans. He gave the Missouri mob 15 minutes to leave town. Then a gang estimated at about 40 persons from Denmark “determined to raise the siege” and, according to a reminiscence by Lindsey Coppock, a relative to one of the eyewitnesses, “with their bayonets in trim,” arrived and then some scattered violence ensued. The Missouri vigilantes quickly capitulated, but only after the Fraziers, Pickering, Comber, Way, and 14 others signed a pledge to appear in the federal district court for their actions in allegedly helping Ruel Daggs’s runaway slaves escape. By Friday, June 9, an interstate battle over slavery had been momentarily abated.[27]

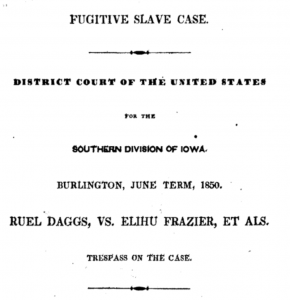

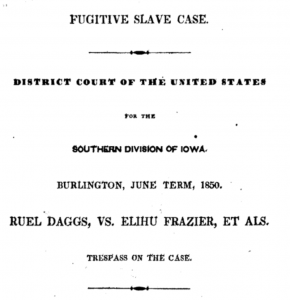

Case report by George Frazee, 1850

Events in Salem were settled for just three months before Salem’s abolitionists entered in Ruel Daggs’s legal crosshairs. In September 1848, Daggs officially filed a $10,000 lawsuit against 19 men for the loss of five runaways and to offset cost for the services of his four slave catchers. The case Ruel Daggs v. Elihu Frazier et al. was finally heard in June 1850 with newly confirmed U.S. District Judge John James Dyer, a graduate of the University of Virginia, presiding. After engaging in private practice in Pendleton County, Virginia and Dubuque, Iowa from 1833 to 1847, Dyer had stepped into the federal judgeship on March 3, 1847, just a year after Iowa’s admission to the Union.[28]

Dyer acknowledged during the trial that the events in Salem were part of growing national divisions over slavery wherein proslavery and antislavery persons maintained a “warlike attitude,” especially over what to do with new territory recently obtained from Mexico. He also noted the addition tensions over the recent increases in large scale escapes from Maryland into Pennsylvania, Kentucky into Ohio, and Missouri into either Iowa or Kansas. Dyer, who had arrived in Iowa by way of the slave state of Virginia, reminded the jury before it deliberated that the Court’s “business now is with the laws and Constitution as they are, not as we may think they ought out be.” He advised the panel to adjudicate based on the 1793 Fugitive Slave Law, which imposed a hefty financial penalty on any person “knowingly and willingly” obstructing hindering, harboring, or concealing freedom seekers.[29]

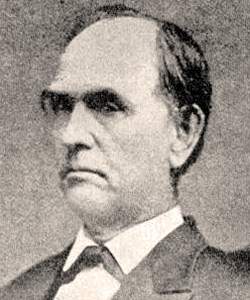

Augustus Caesar Dodge (House Divided Project)

However, the verdict did not end matters. The defendants’ attorneys soon asked permission to file a bill of exceptions with the intention of appealing the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. However, the strategy seemed to be one merely of delay. None of the defendants except for Paul Way was worth the amount levied by the court. All (or most) of them, however, apparently sold their property to their kin ahead of the trial with the aim of avoiding paying any penalty to Daggs. Accordingly, Daggs was never actually paid the fine that the verdict promised.[32] As noted by historian Robert R. Dykstra, the defendants’ decision to liquidate their estates before the trial might be considered “intent to defraud a creditor,” and yet they never faced either a reckoning on the funds nor a challenge to their financial maneuvering. As Lowell Soike put it, Daggs “never collected a dime” and gave up his pursuit in disgust.[33]

AFTERMATH

Historian Lowell J. Soike has called this case “the last federal case decided under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.”[34] The controversies surrounding the case certainly contributed to the debates about strengthening the federal fugitive slave law in 1850. Both of the Hawkeye US senators, Augustus Caesar Dodge and George Wallace Jones, voted for the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, as part of the Compromise of 1850, just months after the Ruel Daggs v. Elihu Frazier et al. decision.

There is a great deal of information about the participants in the 1848 Daggs escape. According to the 1850 Slave Schedule of Clark County, Ruel Daggs sold all but six of his enslaved persons not long after the episode. While his case was undergoing review in the U.S. District Court, he still possessed three males ages 55, 30, and 1; and three females, ages 40, 20, and 20.[35]

Ruel Daggs died in December 1862. (Find A Grave)

Daggs, who had 10 children (six sons, four daughters) to his wife of 61 years, Nancy Johnston (1777-1861), died on December 16, 1862 at age 87. He had married Nancy (originally Nancy Frazier, she had previously married then became a widow) in Kanawha County, Virginia (now West Virginia) on April 26, 1800. All 10 of his children were born in Kanawha. He is buried in Daggs Homestead Cemetery, located 3.5 miles South East of Luray, Missouri. His son George, who assisted in assembling a slave catching posse in June 1848, ended up in California, separated from his wife. Ruel’s other son who assisted in the rendition of his lost slave property, William Rodney, was actually the elected justice of the peace of Washington Township and storeowner in Luray, Clark County. He ended up buying out the rights of his siblings and after Ruel’s death and built a new home on the family’s farm property. He had a cemetery constructed on the property, too, which is now the burial location of his children and the children of the enslaved on the Daggs farm. William Rodney was married twice and had 15 children (three to his first wife, Sarah Martin, 12 to his second wife Sarah Josephine Martin).

Judge Nelson Gibbs (1823-1903), the abolitionist-friendly justice of the peace in Salem that acquitted the runaways remained in that position until 1855. He eventually joined the Republican Party and worked as the sheriff of Hardin County, Iowa between 1867 and 1871. The importance of his office in the Henderson Lewelling House located today at 401 South Main Street in Salem has already been noted as both a national landmark and a recognized Underground Railroad site. The other judge in this episode, John J. Dyer, remained in his federal seat on the U.S. District Court for the District of Iowa until his death on September 14, 1855. He died on a visit to his home in Virginia.

The most remarkable post-escape story concerns the fate of Julia Fulcher. As noted earlier, Samuel Slaughter and James McClure had recaptured Julia, the pregnant 18-year old during the 1848 incident. Julia was thus re-enslaved but eventually obtained her freedom after the Civil War. At some point, Julia married Hezekiah Hall. For a decade after the war, Julia and Hezekiah lived and worked as sharecroppers on a local Missouri farm owned by Scott Miller. Together, they obtained a reputation for their industry, having worked the Miller farm, according to their son, with “honest, sweat and toil, minding their own business and managing their meager funds to the best of ability.” In 1875, they rented a 100-acre farm from Judge Givens near Waterloo, Missouri. They “did so well that they were able to purchase the farm from Judge Givens in a few years.”[36] To date, no evidence has surfaced about whether Julia gave birth to a healthy baby after the 1848 incident. On August 4, 1866, she delivered a boy named Samuel. Julia and Hezekiah also had a daughter named Vicey. Samuel married Lulu Mae Cole on October 29, 1902. Samuel and Lulu were still living on the family farm in Waterloo as late as 1956.

FURTHER READING

A search through digital archives will yield some important newspaper articles about the Daggs Escape. The June 1848 incident, which includes the hearing in front of Justice of the Peace Nelson Gibbs and the invasion by the Missouri mob, was covered in national newspapers like the New York Evening Post and New York Herald. There are also local papers that utilized correspondents to inform local communities about the event in Salem, Iowa. These papers include the Talladega Reporter (Talladega, AL), Louisville Daily Courier (Louisville, KY), Palmyra Whig (Palmyra, MO), Burlington Hawk-Eye (Burlington, IA), Evening Times-Republican (Marshalltown, IA), and The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, IA). George Frazee, member of the Iowa State Bar Association, recorded the full account of Ruel Daggs v. Elihu Frazier et al. case heard by Judge John J. Dyer in the U.S. District Court in June 1850. Frazee’s dictation includes sworn depositions and cross examinations by members of each side of the case, with testimony from some members of Ruel Daggs’s party, including George Daggs, who was responsible to round up a slave catching posse; Samuel Slaughter, the slave hunter from Farmington, Iowa that assisted James McClure and the Daggs family in pursuit of the nine freedom seekers; and Jonathan Pickering, who testified against his brother John H. Pickering. Testimony is also offered of those in the defense; in particular, Albert Button, the counsel to Daggs’s escaped slaves; and Jonathan Frazier, the son of Thomas Clarkson Frazier, the driver of the wagon carrying Daggs’ freedom seekers. Frazee also includes the voices of the seemingly neutral parties, such as school teacher Reuben Dorland who stood on top of a pile of boards to announce the nine runaways should be taken for Judge Gibbs; and Lewis Taylor, an eyewitness that attended the hearing before Judge Gibbs.

A great deal of information about Ruel Daggs and his children can be found in Harold Alan Daggs’s March 23, 1988 recollection titled “Daggs Family History.” It is a 28-page family history and reminiscence that presents short biographical portraits of Ruel Daggs, all of his children, as well as his wife, Nancy. The author is also transparent in sharing details about the family’s relocation from Virginia with its slave estate, including members of the family who were slaveholders and how much enslaved persons were worth. A small portion of the reminiscence recalls the 1848 Daggs Escape.

There are three important secondary sources concerning the Daggs Escape. The oldest source is by O. A. Garretson titled “Traveling on the Underground Railroad in Iowa” and published in the Iowa Journal of History and Politics and The Palimpsest, a publication of Iowa history by the University of Iowa. Written about 1900, Garretson’s account covers abolition activity in Salem, Denmark, and along the border with Kansas. A significant portion of the essay focuses on the Daggs Escape. Readers should be attentive, however, to the numerous minor inaccuracies in the Garretson account that have since been corrected by historians Robert R. Dykstra’s Bright Radical Star: Black Freedom and White Supremacy on the Hawkeye Frontier (1993) and Lowell J. Soike in Necessary Courage: Iowa’s Underground Railroad in the Struggle against Slavery (2013). Perhaps the most noteworthy contradiction among the three voices is how the fate of Daggs’s nine runaways is portrayed. While Dykstra and Soike are clear that five of the nine eluded recapture–a point confirmed by all of the primary source documentation, including the June 1850 Ruel Daggs v. Elihu Frazier et al. U.S. District case–Garretson incorrectly claims that every freedom seekers made it to Canada. Why the discrepancy? Garretson’s version of the Daggs Escape appears to be his retelling of an as-told-to account from a relative. In his article, Garretson is proud to reveal that at least two ancestors (Joel Garretson and John Garretson) were involved in preventing Daggs’s slave catchers from succeeding. He explained that both family members were fervent abolitionists: Joel was among “the instigators of the plot to free their [Missouri’s] slaves” while John used his personal carriage to feed and shelter freedom seekers from kidnappers. On the contrary, Soike’s 2013 account of the events described in Necessary Courage relies on testimony from the 1848 Salem hearing in front of Judge Gibbs and 1850 U.S. District Court trial, along with a variety of national and local newspaper coverage. Soike, a former director of the Iowa Freedom Trail Project, was able to reconstruct the proceedings through depositions given by the slave hunters and Salem townspeople. It is still perhaps best to read Robert R. Dykstra’s 1993 interpretation of events surrounding the escape of Ruel Daggs’s nine runaways, which includes eyewitness testimony of events and a wide range of media coverage during the eight days of June 2 to June 9, 1848 and the subsequent federal district court hearing of June 1850. It is important to note that both Soike and Dykstra include chapters about the Daggs Escape in books that otherwise focus on Iowa’s more general Underground Railroad history. Yet both account do a fine job of placing the events of 1848 in context with the sectional crisis that led to the Civil War.

END NOTES

[1] Soike, 34.

[2] Cincinnati Allas [sic] in “Grand Stampede,” Danville (VT) North Star, May 17, 1847; Covington (KY) Register in “Negro Stampede,” Worcester (MA) Bay State Farmer and Mechanic’s Ledger, May 29, 1847; “Negro Stampede,” The Liberator, July 16, 1847.

[3] Soike, 30-31; Francis A.E. Waters, “Anti-Slavery Sentiment in Iowa,” Washington D.C., National Era, November 21, 1850.

[4] Morgans, 94; Harold Alan Daggs. “Daggs Family.” (genealogy file). March 23, 1988. 11; Lewis D. Savage. “Former Slaves, the Success Story of a Clark County Missouri Farm Family.” Keokuk Daily Gate City, Sam Hall Interview, August 4, 1956. Retrieved at https://connect.xfinity.com/appsuite/#!!&app=io.ox/mail&folder=default0/INBOX

[5] Soike, 33; O.A. Garretson, “Traveling on the Underground Railway.” [Date unknown]. Retrieved at https://web.archive.org/web/20160826081248/http://www.garretson.us/Garretson.us/History_Articles_by_O.A._Garretson.html

[6] Garretson; Daggs, 12.

[7] George Frazee. “An Iowa Fugitive Slave Case – 1850.” 9; Soike, 28, 44; James Patrick Morgans. The Underground Railroad on the Western Frontier. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. 2010, 94-95; Dykstra, 92.

[8] Walter Edgerton, A History of the Separation in Indiana Yearly Meeting of Friends (Cincinnati, 1856), quoted in Robert R. Dykstra. Bright Radical Star: Black Freedom and White Supremacy on the Hawkeye Frontier. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993. 90-91.

[9] Louis Thomas Jones. The Quakers of Iowa. Clio Press, 1914. 189.

[10] Frazee, 10; Daggs, 12-13; “Fugitive Slave Case Was Tried.” The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, IA). April 13, 1915. 5.

[11] Ann-Lisa Cox. A Stronger Kinship: One Town’s Extraordinary Story of Hope and Faith. Little, Brown, Inc. 2009. 34.

[12] Garretson.

[13] The Burlington Hawk-Eye (Burlington, IA). July 11, 1850. 1; Affidavit of James McClure, taken at Farmington, Iowa, Daggs Case File, October 9, 1848 and “Deposition of Henry Brown,” taken at Fairfield, Iowa, Daggs Case File, March 22, 1850 quoted in Soike, 33; District Court of the United States. Southern Division of Iowa. Burlington, Iowa, June Term, 1850. Hon. J. J. DYER. presiding. Ruel Daggs, plaintiff, vs. Elihu Frazier, et al., defendants. Trespass on the Case. 6.

[14] Dykstra, 93.

[15] “Ruel J. Daggs.” Find A Grave. Retrieved at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/29216157/ruel-j_-daggs

[16] Soike, 34-35; Garretson; Jones, 189.

[17] Dykstra, 93.

[18] Alabama Reporter (Talladega, AL). July 20, 1848, 4; New York Herald. June 22, 1848. 2.

[19] Soike, 34-35; Jones, 190; Dykstra, 93.

[20] Jones, 190; Dykstra, 93.

[21] Dykstra, 94-95.

[22] George Frazee, Fugitive Slave Case, District Court of the Southern Division of Iowa, Burlington, June Term, 1850, Ruel Daggs v. Elihu Frazier, et al. (Burlington, IA: Morgan and M’Kenny, 1850), 6; Soike, 37; District Court of the United States. Southern Division of Iowa. Burlington, Iowa, June Term, 1850. Hon. J. J. DYER. presiding. Ruel Daggs, plaintiff, vs. Elihu Frazier, et al., defendants. Trespass on the Case. 24-26, 38.

[23] Soike, 38; Garretson; “Fugitive Slave Case Was Tried.” The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, IA). April 13, 1915. 5.

[24] Dykstra, 96.

[25] Soike, 39; Garretson; Jones, 191; “Slave-Catchers in Iowa.” Evening Times-Republican (Marshalltown, IA). March 4, 1914, 4.

[26] Dykstra, 96-97.

[27] “Fugitive Slave Case Was Tried.” The Daily Gate City (Keokuk, IA). April 13, 1915. 5.

[28] James Whitcomb Ellis. History of Jackson County, Iowa, Volume 1. “John James Dyer.” Jackson County, IA: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1910. 564; Ballotpedia. Retrieved at https://ballotpedia.org/John_James_Dyer; Dykstra, 97.

[29] Ellis, 564; U.S. Congress Act of February 12, 1793; Soike, 43-45; District Court of the United States. Southern Division of Iowa. Burlington, Iowa, June Term, 1850. Hon. J. J. DYER. presiding. Ruel Daggs, plaintiff, vs. Elihu Frazier, et al., defendants. Trespass on the Case. 38.

[30] “Missouri Slave Case.” Palmyra Whig. June 20, 1850. 2.

[31] Louisville Daily Courier (Louisville, KY). June 19, 1850. 3.

[32] Dykstra, 103.

[33] Soike, 46.

[34] Soike, 45; Dykstra, 105. Actually, the “last” case under the 1793 federal fugitive slave law as probably Oliver et.al. v. Kauffman, which originated in Carlisle, PA in 1847 but was retried in federal court in 1852.

[35] 1850 US Census Slave Schedule, Ruel Daggs. Retrieved at file:///Users/todd.mealy/Desktop/1850%20Census%20Slave%20Schedules%20Ruel%20Daggs%20.pdf

[36] Lewis D. Savage. “Former Slaves, the Success Story of a Clark County Missouri Farm Family.” Keokuk Daily Gate City, Sam Hall Interview, August 4, 1956. Retrieved at https://connect.xfinity.com/appsuite/#!!&app=io.ox/mail&folder=default0/INBOX

vigilantes were stationed as guards throughout the town. One eyewitness said members of the mob “snapped a pistol at an old crippled man.”

vigilantes were stationed as guards throughout the town. One eyewitness said members of the mob “snapped a pistol at an old crippled man.”