Historical Background

The U.S. Constitution does not employ the phrase “war powers,” but it does grant Congress the power to “declare war” in Article I, Section 8 and to create the armed forces. Yet the Framers clearly intended to leave the operational control of the military in the hands of the president. The Constitution explicitly describes the president in Article II as “commander in chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States.” But what exactly does that mean?

- There was relatively little debate over these issues at the 1787 convention.

- August 17: Delegates discuss war powers. Highlights include:

- Oliver Ellsworth (CT) stating, “It should be more easy to get out of war than into it.”

- George Mason (VA) claiming he “was against giving the power of war to the Executive, because not safely to be trusted with it.”

- August 17: Delegates discuss war powers. Highlights include:

- The Constitution addresses the concept of war powers mainly in three brief clauses.

- Article 1, Section 8, Clause 11 (“The Congress shall have Power … To declare War”)

- Article 1, Section 10, Clause 3 (“No State shall … engage in war, unless…”)

- Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 (“The President shall be Commander in Chief…”)

- There were very few major cases involving war powers between 1789-1861.

Lincoln’s Example

Yet Abraham Lincoln was compelled to provide answers to the questions about how the Constitution defines the war power almost from the outset of his administration. He faced not only a secession movement sparked by his election, but also an unprecedented internal threat to the government. During times of crisis, people always fear spies and sabotage, but in April 1861 there was real and widespread disloyalty among federal office-holders, including even Supreme Court justices, leading military officers, senators, congressmen and powerful bureaucrats. To make matters worse, in a struggle where slavery was “somehow” the cause of the conflict, as Lincoln put it in the Second Inaugural Address, both the nation’s capital and the surrounding states were slave territory. Numerous reports suggested that secessionist sympathizers around Washington aimed to cut off the capital and overthrow the government. With essentially no military experience, having not even visited Washington for a dozen years prior to his inauguration and with Congress out of session, the amiable attorney from Springfield, Illinois seemed ill-prepared for such dire circumstances.

Despite this lack of experience, the new president acted with stunning dispatch. He called up the militia, authorized the expenditure of funds, suspended habeas corpus along the train routes into Washington, and declared an embargo on southern ports –all without congressional approval.

The situation intensified even further at the end of May when the government declined to obey an order from the Chief Justice of the United States, Roger B. Taney, demanding the release a political prisoner named John Merryman who was being held at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. Writing in Ex Parte Merryman (1861), Taney concluded that if Lincoln had his way on the question of civil liberties, “the people of the United States are no longer living under a government of laws.”

Many people and some legal scholars have since characterized Lincoln’s response in utterly pragmatic terms. They claim, usually with a measure of disapproval, that he ignored the Chief Justice and then rationalized his actions with a flat-out utilitarian appeal that expressed itself most famously in a line to Congress from July 1861: “are all the laws, but one, to go unexecuted, and the government itself go to pieces,” he asked, “lest that one be violated?” Lincoln did write those words for a special message delivered to Congress on July 4, 1861, but the question, as profound and troubling as it might be, was one that Lincoln considered to be hypothetical. “But it was not believed that this question was presented,” he stated, adding firmly, “It was not believed that any law was violated.”

Lincoln never once backed down from this claim that his executive actions were legal. According to his view, the Constitution inherently authorized extraordinary measures during periods of rebellion or invasion, especially by a president who was “vested” with the nation’s “executive power” and bound by oath to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” This was an argument Lincoln repeated on numerous occasions, but toward the end of the Civil War, he put the issue in its clearest and most profound terms. “I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful,” he wrote on April 4, 1864, “by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it.”

- Article I, Section 9, Clause 2

- Ex parte Merryman (May 25, 1861)

- Message to Congress (July 4, 1861)

- Letter to Albert Hodges (April 4, 1864)

Modern Debates

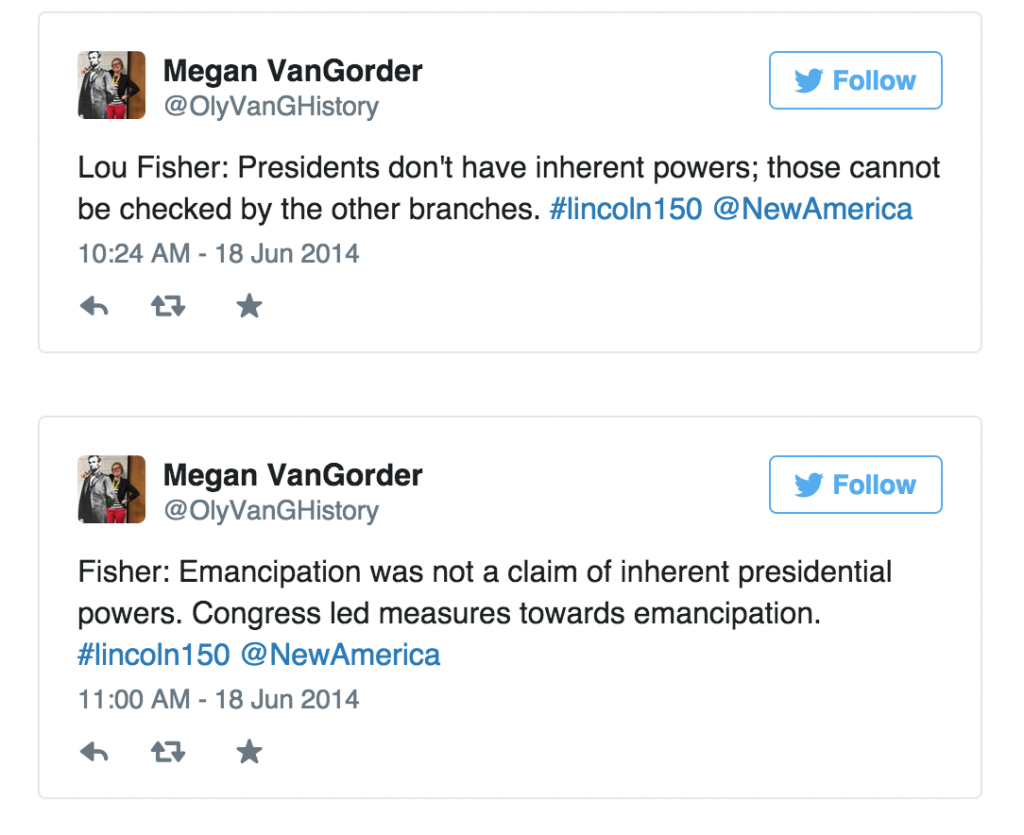

In June 2014, a panel of experts came together at the New America Foundation in Washington DC to discuss how the perennial questions about war powers have evolved since Lincoln’s day. “Understanding Lincoln” course instructor Matthew Pinsker served as panel moderator. Panelists included attorney John Altenburg, journalist Sidney Blumenthal, Congressional scholar Louis Fisher, and Dr. Jeffrey McCausland of the Strategic Studies Institute at the US Army War College. For more information on the panelists, see this press release.

Course participant Megan VanGorder (an educator from Illinois) live tweeted much of the panel. She captured one particularly relevant exchange between Fisher and Pinsker.

On that last point about emancipation, Pinsker indicated that he disagreed with Fisher, but they ran out of time to examine why. The problem, from Pinsker’s perspective, is that Lincoln’s use of emancipation was “inherent” by Fisher’s or anyone’s standards and far exceeded the ordinary bounds of presidential authority. Congress did push emancipation policy forward through their confiscation acts (1861, 1862) as Fisher suggested, but Lincoln’s actual exercise of emancipation powers was more sweeping than Pinsker thinks Fisher allows. This is an important debate for the modern-day classroom. You can read more about Lou Fisher’s views at his website. He is arguably the nation’s premier scholar on separation of powers issues.

Pinsker’s approach in his classroom is to teach war powers not as a separation of powers, but rather as a chronology of powers. He thinks war powers are ordered in time with the president almost always taking the initiative. To find out more about this perspective, see the next pathway in this exhibition. To view the full June 2014 war powers panel, click on the video below.