Contributing Editors for this page include Brian Elsner and Thomas Warf

Ranking

#51 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, October 25, 1862

The Lincoln Log, October 25, 1862

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” course participant Thomas Warf, August 2014

Brian Elsner, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), October 7, 2013

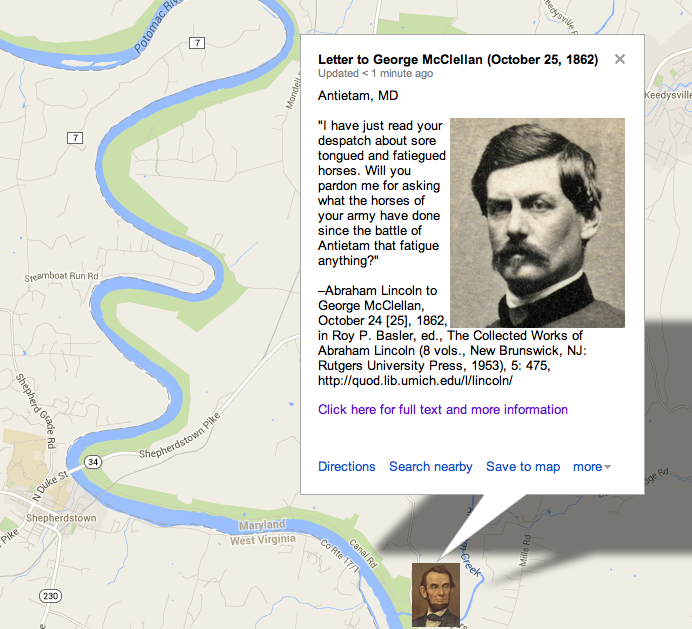

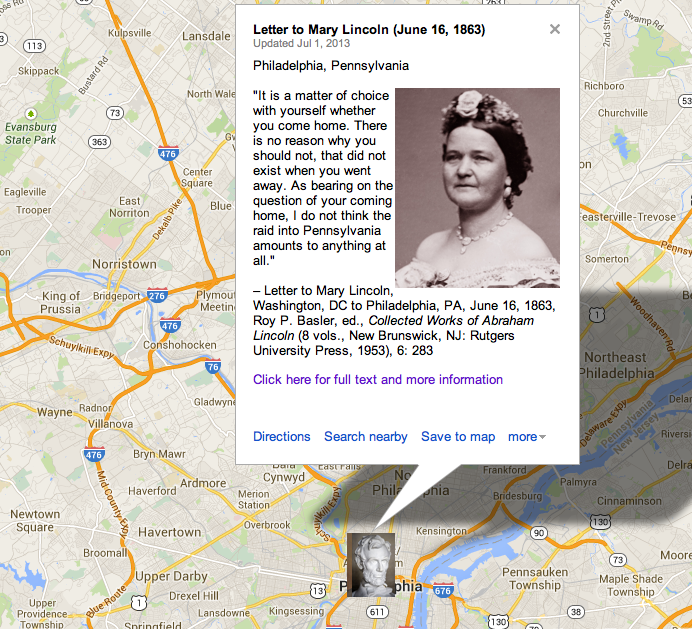

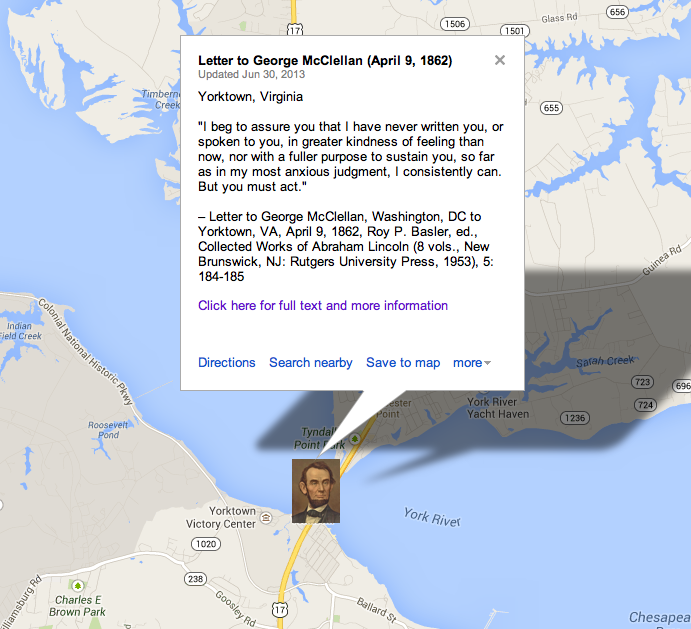

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“In response to McClellan’s explanation that his horses were exhausted, Lincoln sent a tart reply through Halleck: ‘The President has read your telegram, and directs me to suggest that, if the enemy had more occupation south of the river, his cavalry would not be so likely to make raids north of it.’ Shortly thereafter, Lincoln more pointedly wired the Young Napoleon: ‘I have just received your dispatch about sore tongued and fatiegued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigue anything?’ Indignant at what he considered a ‘dirty little fling,’ McClellan sent a lengthy report on his cavalry but failed to deal with Lincoln’s larger point, that the army’s inactivity threatened the war effort.”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 29 (PDF), 3150.

“On October 25, the War Department received a cavalry report forwarded by McClellan. In it, a Massachusetts cavalry colonel reported that 128 of his 267 horses were too ill or disabled to leave camp and that ‘the horses, which are still sound are absolutely broken down from fatigue and want of flesh.’ This report provided Lincoln with an outlet for his frustration as he wired McClellan, ‘I have just read your dispatch about sore tongued and fatiegued [sic] horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietem that fatigue anything? McClellan responded with a list of cavalry activities and defiantly concluded ‘If any instance can be found where overworked Cavalry has performed more labor than mine since the Battle of Antietam I am not conscious of it.’ Not surprisingly, McClellan missed the point of Lincoln’s jab.”

–Edward H. Bonekemper, III, McClellan and Failure (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2007), 151.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln