Ranking

#19 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

Context. In the fall of 1837, an abolitionist newspaper editor named Elijah Lovejoy was murdered by a pro-slavery mob while trying to defend himself and his printing presses near Alton, Illinois. The murder riveted and polarized the nation, and although Abraham Lincoln did not mention Lovejoy by name in his speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum in January 1838, most historians consider it obvious that he had the incident in mind as he deplored mob violence and urged Americans to uphold their faith in law and republican institutions. In the excerpts from the speech below, Lincoln focused on the threat from what he termed a “Towering genius” who might disturb the successful American experiment in self-government because he desired a new form of glory. Lincoln ominously warned that such a figure might assert himself by “emancipating slaves” or “enslaving free men.” Lincoln was merely in his late twenties at that time, a young, novice attorney and state legislator, still unmarried and renting a room above a store in town. (By Matthew Pinsker)

“That our government should have been maintained….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, January 27, 1838

Image Gallery

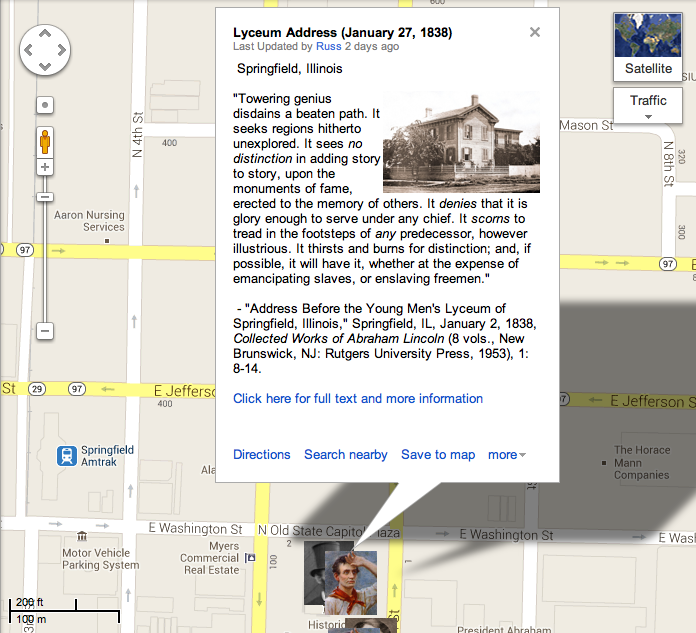

- Springfield, Illinois

- Alton, Illinois

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Lyceum Address (1838) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Elijah Lovejoy, Letter to the Editor of Emancipator, The Liberator, November 10, 1837

“The Death of Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy…,” The Liberator, December 8, 1837

How Historians Interpret

“The day that this article appeared, Lincoln gave a speech to the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield. Titled ‘The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions,’ it focused primarily on recent outbreaks of mob violence, which Lincoln roundly condemned, adding his voice to the Illinois Whig chorus denouncing the upsurge in riots and lynching. (A year earlier he had attacked ‘that lawless and mobocratic spirit…which is already abroad in the land.’) … In the midst of his ostensibly nonpartisan address, Lincoln slyly alluded to the danger posed by a coming Caesar, a man ‘of ambition and talents’ who would ruthlessly pursue fame and power, overthrowing democratic institutions to achieve his ends. Rhetorically, Lincoln asked if such a person would be content to follow traditional paths to distinction: … Since the rules of the Lyceum forbade political speeches, Lincoln could not directly attack Douglas, but because his audience was politically aware, he could assume that they had read ‘Conservative No.2’ earlier in the day and thus understood that Douglas was the target of his remarks about the coming Caesar. It was evidently a clever maneuver to circumvent the ban on partisanship at the Lyceum.”

“The lecture was written for yet another great agency of American oratory, the town lyceum (in this case, the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, one of a nationwide network of 3,000 such speech-making societies begun by Josiah Holbrook in 1826), and Lincoln took as his topic exactly the question of how to guarantee “The Perpetuation of our Political Institutions.” His answer to the temptations of power was not an appeal to Jeffersonian virtue, but to the countervailing authority of law. Any glance around the American scene would reveal ‘accounts of outrages committed by mobs,’ leading to disgust across the republic with ‘the operation of this mobocratic spirit’ and finally a resort to a dictator who, like Napoleon, would promise order but deliver despotism. The only preventative was for ‘every lover of liberty’ to ‘swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others.'”

— Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln: A Very Short Introduction, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 47

“Lincoln began writing his historical drama in his much-remarked Lyceum Address delivered in Springfield in January of 1838. At the time, he was twenty-eight and had little reason to suspect, despite the distance he had already traveled from his hardscrabble days as a farm boy on the middle border, that he would become a central figure in his own story. The subject of Lincoln’s speech was how and whether the extraordinary political institutions of the United States could be sustained in the face of challenges of a different sort to the next generation of Americans. As James Russell Lowell had written, ‘It is only first-rate events that call for and mould first-rate characters.’ … In Lincoln’s rendering of these themes in the Lyceum speech, the sons of the Founders – his generation – were denied the opportunities for greatness afforded their sanctified fathers who fought the American Revolution and then wrote the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The heroic Founders had taken possession of the land and built ‘a political edifice of liberty and equal rights.’ They sought immortality through acts of creation. ‘If they succeeded, they were to be immortalized; their names were to be transferred to counties and cities, and rivers and mountains; and to be revered and sung and toasted through all time..They succeeded.'”

Further Reading