Ranking

#6 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“If we could first know where we are….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, June 16, 1858

Image Gallery

- Lincoln in 1858

- Roger Taney in 1858

- Stephen Douglas in 1858

- Dred Scott

- Kansas territory map

- State Capitol, Springfield, IL

- Springfield State Capitol (interior)

- Sectionalism cartoon (1856)

- Sectionalism cartoon (1860)

- Kansas cartoon (1856)

Close Readings

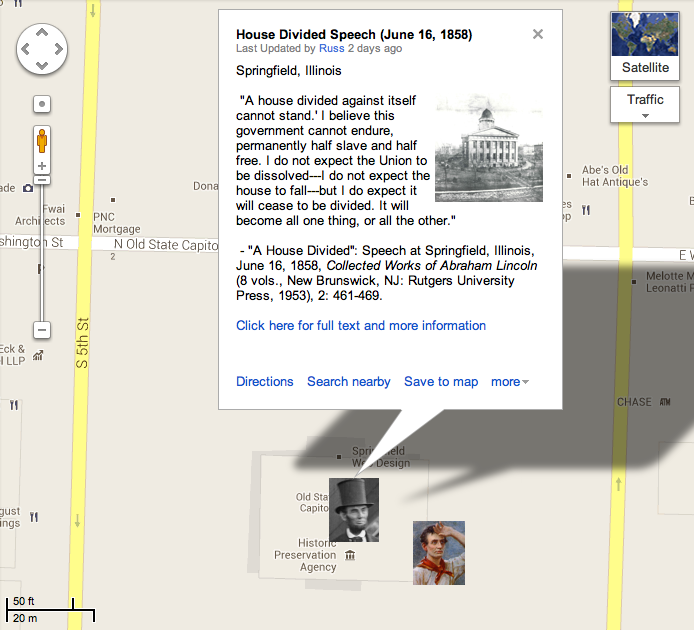

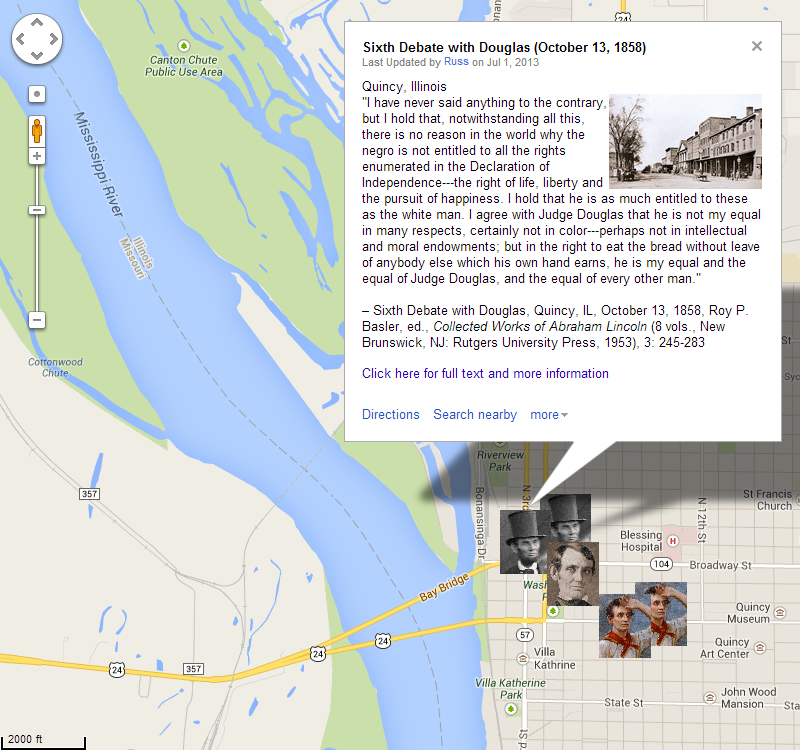

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Abraham Lincoln, “Fragment of a Speech, c. December 28, 1857

Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln, “First Debate,” Ottawa, Illinois, August 21, 1858

John L. Scripps to Abraham Lincoln, June 22, 1858

Abraham Lincoln to John L. Scripps, June 23, 1858

R. P. Stevens to Abraham Lincoln, June 24, 1858

Chicago Press and Tribune, “New Orleans Delta on the Illinois Republican Convention,” July 5, 1858

Oliver P. Hall, et al. to Abraham Lincoln, January 9, 1860

Abraham Lincoln to Oliver P. Hall, Jacob N. Fullinwider, and William F. Correll,” February 14, 1860

Abraham Lincoln, “Certified Transcript of Passage from the House Divided Speech,” December 17, 1860

How Historians Interpret

“Lincoln’s other prediction – regarding a second Dred Scott decision – was not far- fetched.197 The Bloomington Pantagraph had mentioned the possibility of a second Dred Scott case less than a week after the Supreme Court ruled in the first one.198 Lincoln was probably alluding to Lemmon vs. the People, a case which had begun in New York in 1852 and dealt with the right of slaveholders to take their chattels with them into Free States. In 1841, the New York legislature had overturned an earlier statute permitting slave owners to visit the Empire State accompanied by slaves for temporary sojourns. The new law stipulated that “no person imported, introduced or brought into this State” could be held in bondage. In October 1857, it was argued before the New York Supreme Court, which upheld the statute by a 5-3 vote. As the case was being considered by the state’s Court of Appeals, opponents of slavery feared that it would eventually come before the U.S. Supreme Court, where Taney and his colleagues might overrule New York’s statute and pave the way for nationalizing slavery. The case was pending in 1858 and not argued before the New York Court of Appeals until 1860.”

“Attracting national attention, Lincoln’s house-divided speech sounded very radical. Advanced five months before William H. Seward offered his prediction of an ‘irrepressible conflict’ between slavery and freedom, it was the most extreme statement made by any responsible leader of the Republican party. Even Herndon, to whom Lincoln first read it, told his partner: ‘It is true, but is it wise or politic to say so?’ Lincoln’s other advisers condemned it, especially deploring the house-divided image and saying ‘the whole Spirit was too far in advance of the times.’ As the editor John Locke Scripps explained, many who heard and read Lincoln’s speech understood it as ‘an implied pledge on behalf of the Republican party to make war upon the institution in the States where it now exists.'”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 209

“As a senatorial candidate in 1858, Lincoln fought Douglas on ground of the incumbent senator’s own choosing: the legitimacy of popular sovereignty as a republican principle. Lincoln’s acceptance came in the famous ‘House Divided’ speech. By the time Lincoln spoke, both antislavery and proslavery writers had used the metaphor of the house divided to argue that the United States could not be both free and slave. One premise of Douglas’s popular sovereignty, of course, was that it could be both. Lincoln not only rejected that premise, he questioned Douglas’s sincerity in asserting it, arguing that Douglas really intended to nationalize slavery . . . ‘Popular Sovereignty, as now applied to the question of slavery, does allow the people of a Territory to have slavery if they want to, but does not allow them not to have it if they do not want it.’”

“So did the charges that Republicans were disunionists. At times Lincoln fed those allegations; his House Divided speech forecast the nation split in two and division made imperative because either freedom or slavery must triumph. But the future president was quick to deny that accusation. What was at stake, he claimed, was a struggle for the minds of men over the question of whether slavery or freedom controlled the territories and hence the future. It was a debate that would be resolved not with invasion or threat, but through the political discourse that would lead the people and their government toward their original idealism. That reassurance actually only promised Dixie a slow death for slavery if people like Lincoln won office. But it did suggest how a healthy political-constitutional process could bring to life the Declaration’s egalitarian promise. That too pushed Lincoln toward redefining the meaning of 1776.”

Further Reading

Searchable Text