Ranking

#115 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, March 27, 1863

The Lincoln Log, March 27, 1863

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

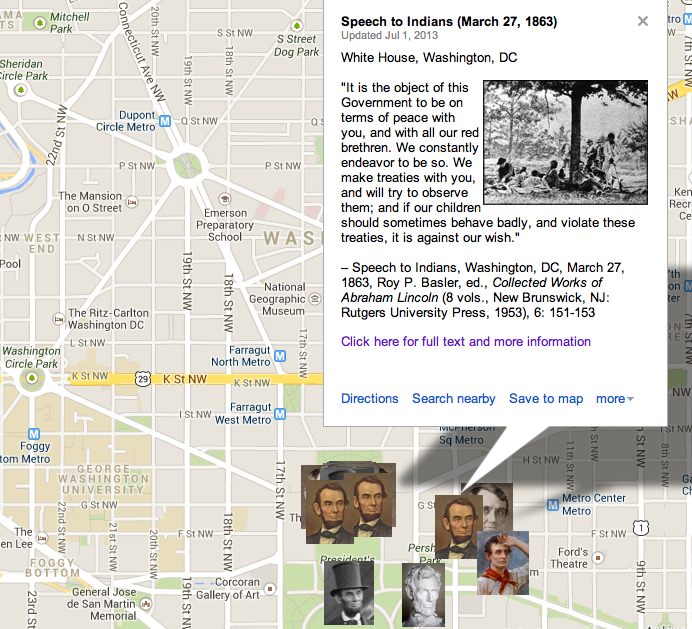

“Lincoln felt that, ideally, American should be white. He explained to a black delegation in 1862 that the white and black races could not coexist in the nation, adding that the presence of blacks in America was currently causing white people to fight each other. The next year, in March, Lincoln met with Indian leaders. He had not known many Indians. He began by explaining that the world is round. . .He then considered the ‘great difference between this pale-faced people and their red brethren both as to numbers and the way in which they live.’ Indians, he said, live by hunting, whereas white people farm, and ‘I can only say that I can see no way in which your race is to become as numerous and prosperous as the white race except by living as they do.’ Lincoln also told his Indian listeners of another difference between the two races: ‘Although we are now engaged in a great war between one another, we are not, as a race, so much disposed to fight and kill one another as our red brethren.’ One might had thought that the carnage of a civil war between white people, widely understood as such at the time, would have undermined the belief in white civilization as superior, not to mention more peaceful—perhaps even have undermined the belief in whiteness itself. White people were killing each other all around Lincoln; he was himself directing much of the killing; and so his seemingly mad assertion of the white race’s comparative amiability must have answered a deep need to take an observable, unattractive feature of white behavior and attribute it to another race. If that race were removed from the nation, then would not the unwanted behavior cease as well? In which case the white American race could advance to prosperity and reach that destiny uniquely its own. The Civil War, however, was a truly American conflict; all three races fought on both sides. A majority of Indians fought for the Confederacy. . .Yet Indians in the Northern ambit, and some without, fought for Lincoln. . . Everyone’s racial fate was in the balance during the Civil War. . .”

“Lincoln admitted that he was poorly informed on Indian affairs. . .In general, like most whites of his generation, he considered the Indians a barbarous people who were a barrier to progress. The ceremonial visits of Indian chiefs, dressed in their tribal regalia, he welcomed, both because they were exotic and because he rather enjoyed playing the role of their Great Father, addressing them in pidgin English and explaining that ‘this world is a great, round ball.’ Occasionally, as during the following year, he would offer them little homilies on how they could profit by learning the ‘arts of civilization.’ Pointing out that the ‘great difference between this pale-faced people and their red brethren,’ he told a group in the White House that whites had become numerous and prosperous partly because they were farmers rather than hunters. Even though he admitted that ‘we are now engaged in a great war between one another,’ he also offered another reason for white success: ‘We are not, as a race, so much disposed to fight and kill on another as our red brethren.’ The irony was unintentional.”

–David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 393

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln