Contributing editors for this page include Matthew Heys

Ranking

#76 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

On This Date

HD Daily Report, January 11, 1837

The Lincoln Log, January 11, 1837

Close Readings

Posted at YouTube by “Understanding Lincoln” participant Matthew Heys, 2016

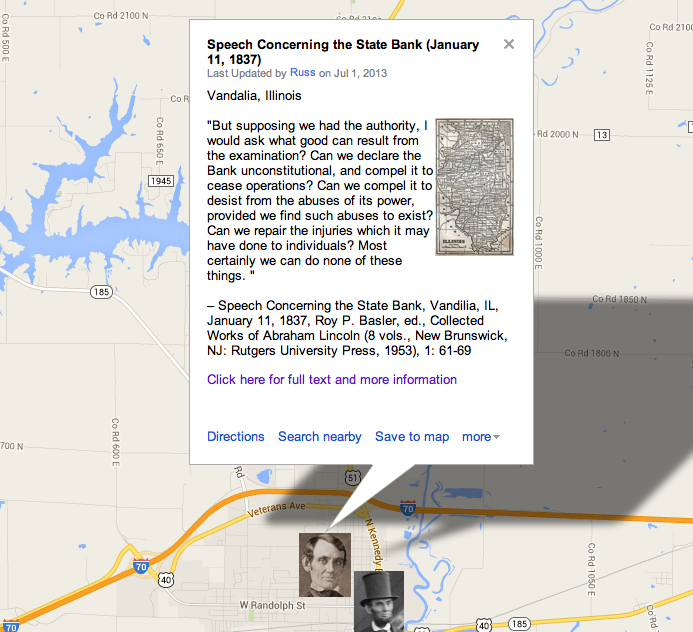

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“In the 1830s and ‘40s Lincoln consistently defended both state and national banking. To him, the assault on the Bank of the United States was part of a general breakdown of respect for property and morality that was also manifesting itself in lynch law.”

Daniel Walker Howe, The Political Culture of the American Whigs (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1979), 265.

“In this partisan speech, Lincoln did not forthrightly address all the criticisms of the bank. When the legislature incorporated the Bank of Illinois, it anticipated that its stock would be bought primarily by in-state investors. Instead, most shares were purchased by financiers in the East who deviously used the names of Illinois farmers as “owners” of the stock. Linder had justly accused the bank commissioners of violating the law. This Lincoln dismissed as a quarrel among selfish capitalists which was of no concern to the people. In fact, the law had been undermined. Lincoln was also disingenuous in alleging that the bank had met its legal requirement to redeem its notes in specie. This provision of the law was virtually nullified through clever arrangements by which the nine branches of the Bank of Illinois printed notes which could only be redeemed at the issuing branch. To ensure that few such requests for redemption were made, the branches brought their notes into circulation at remote sites. Though somewhat demagogic, Lincoln’s speech was predicated on the sound notion that economic growth required banks and an elastic money supply. His political opponents, with their agrarian fondness for a metallic currency, failed to understand this fundamental point. Banks, he knew, had a vital role to play in financing the canals and railroads essential for ending rural isolation and backwardness, a goal he cared about passionately.”

Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 1, Chapter 4 (PDF), 375.376.

“During his first two terms as a representative, Lincoln no doubt had numerous chances to speak, but the address to the Illinois house on the state bank (January 11, 1837) was the first of his speeches to be published verbatim. It is notable both for a persistent personal attack on Usher F. Linder (a Democrat from Coles County, Linder had introduced resolutions calling for a select house committee to investigate the troubled state bank) and for the sophistical logic and rhetoric Lincoln used to extend his ad hominem and dismantle the opposition’s arguments.”

Robert Bray, “’The Power to Hurt’: Lincoln’s Early Use of Satire and Invective,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 16, no.1 (1995): 39-58.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

…Immediately following this last charge, there are several insinuations in the resolution, which are too silly to require any sort of notice, were it not for the fact, that they conclude by saying, “to the great injury of the people at large.” In answer to this I would say, that it is strange enough, that the people are suffering these “great injuries,” and yet are not sensible of it! Singular indeed that the people should be writhing under oppression and injury, and yet not one among them to be found, to raise the voice of complaint. If the Bank be inflicting injury upon the people, why is it, that not a single petition is presented to this body on the subject? If the Bank really be a grievance, why is it, that no one of the real people is found to ask redress of it? The truth is, no such oppression exists. If it did, our table would groan with memorials and petitions, and we would not be permitted to rest day or night, till we had put it down. The people know their rights; and they are never slow to assert and maintain them, when they are invaded. Let them call for an investigation, and I shall ever stand ready to respond to the call. But they have made no such call. I make the assertion boldly, and without fear of contradiction, that no man, who does not hold an office, or does not aspire to one, has ever found any fault of the Bank. It has doubled the prices of the products of their farms, and filled their pockets with a sound circulating medium, and they are all well pleased with its operations. No, Sir, it is the politician who is the first to sound the alarm, (which, by the way, is a false one.) It is he, [who,] by these unholy means, is endeavoring to blow up a storm that he may ride upon and direct. It is he, and he alone, that here proposes to spend thousands of the people’s public treasure, for no other advantage to them, than to make valueless in their pockets the reward of their industry. Mr. Chairman, this movement is exclusively the work of politicians; a set of men who have interests aside from the interests of the people, and who, to say the most of them, are, taken as a mass, at least one long step removed from honest men. I say this with the greater freedom because, being a politician myself, none can regard it as personal.