Ranking

#42 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, April 19, 1861

The Lincoln Log, April 19, 1861

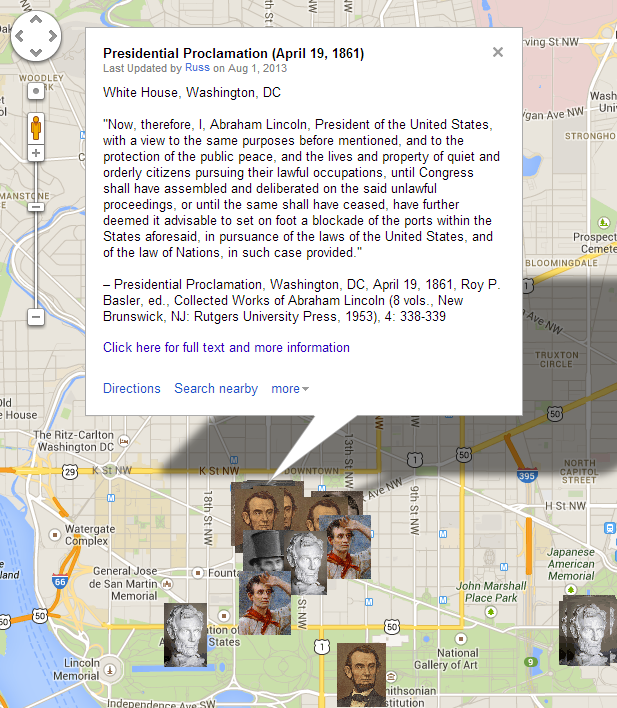

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“It is not surprising that many observers at home and abroad should have regarded Lincoln as a man patently out of his depth in a crisis of such magnitude. To the London Times, for instance, he seemed weak, dilatory, and destined to be more of a follower than a leader in the conduct of the government. Yet the very confusion of circumstances, the very uniqueness and urgency of the problems confronting him, amounted to a slate wiped clean, offering an extraordinary opportunity for the exercise of leadership. How did Lincoln respond? Decisively, beyond question. Within the first three weeks following the attack on Fort Sumter: He issued proclamations of a blockade, dated April 19 and 27, that were tantamount to declaring the existence of a state of civil war.”

— Don E. Fehrenbacher, “Lincoln’s Wartime Leadership: The first Hundred Days,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 9, no. 1 (1987), 2-18.

“While these actions may have bent the Constitution slightly, more serious extraconstitutional steps were also taken in the ten weeks between the bombardment of Sumter and the convening of Congress in July. Lincoln acted unilaterally in the belief that his emergency measures would be endorsed retrospectively by the House and Senate and thus made constitutional. On April 19, he declared his intention to blockade ports in the seven seceded states; a week later he extended it to cover Virginia and North Carolina. This he justified as a response to the Confederacy’s announcement on April 17 that it would issue letters of marque, authorizing privateers to seize Union shipping. In the momentous cabinet session of April 14, a majority agreed with Gideon Welles, who maintained that a blockade was more appropriate for a war between two nations rather than for a rebellion. Better to simply close the ports in the seceded states, argued the navy secretary, who understandably feared that the Union fleet was too small and antiquated to enforce a blockade. Bates believed that a blockade was ‘an act of war, which a nation cannot wage against itself’ but that closing ports was ‘altogether different.’ Seward, however, countered that closing Southern ports might provoke foreign nations to declare war. Lincoln at first sided with Welles, but Seward took him ‘off to ride, explained his own view,’ and the president gave in. The following day he told the cabinet and ‘that we could not afford to have two wars on our hands at once’ and therefore he would declare a blockade.”

— Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 23 (PDF), 2459-2460.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln