Ranking

#21 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

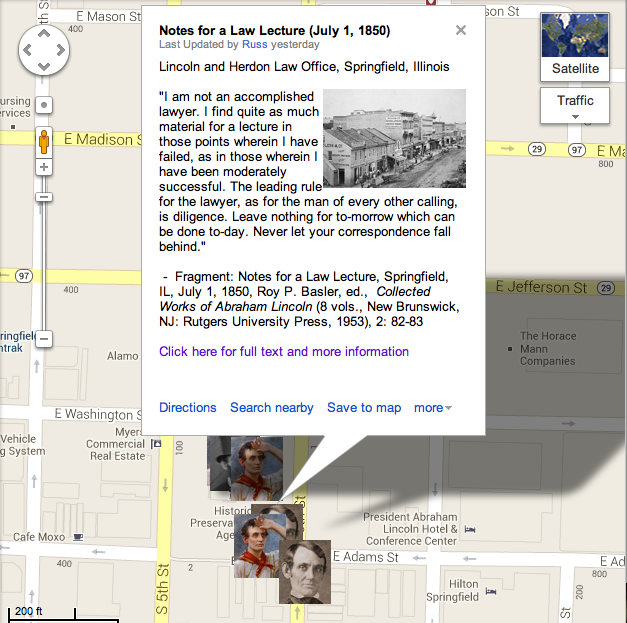

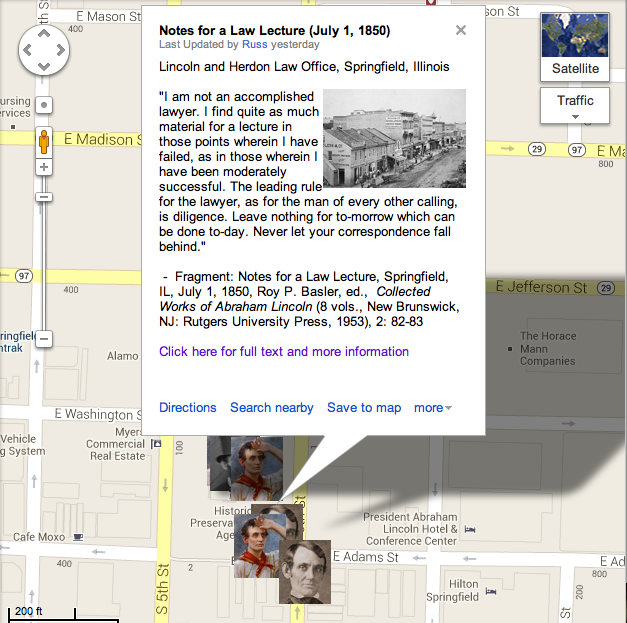

Context. The editors of Abraham Lincoln’s Collected Works have tentatively dated this fragment found in his papers as July 1, 1850. It appears to have been the draft of a speech that Lincoln must have given to younger members of the Illinois bar during the period in the early 1850s when he was most active as a circuit-riding attorney. In these notes, Lincoln offered a series of common sense observations about how to succeed in the legal profession (or any profession), but he punctuated his remarks by emphasizing the need for honesty, a standard he seemed especially determined to meet in his own career. (By Matthew Pinsker)

“I am not an accomplished lawyer….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, July 1, 1850

Image Gallery

-

-

Lincoln in 1846

-

-

Image of Notes for Law Lecture

-

-

Lincoln in white suit

-

-

Lincoln as Lawyer stamp

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Notes for Law Lecture (1850) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Custom Map

View in Larger Map

Other Primary Sources

How Historians Interpret

“In handling hundreds of cases in the circuit courts, Lincoln firmly reestablished his reputation as a lawyer. It was a reputation that rested, first, on the universal belief in his absolute honesty. He became known as ‘Honest Abe’—or, often, ‘Honest Old Abe’—the lawyer who was never known to lie. He held himself to the highest standards of truthfulness.”

—David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 149

Further Reading

For educators:

For everyone:

Searchable Text

I am not an accomplished lawyer. I find quite as much material for a lecture in those points wherein I have failed, as in those wherein I have been moderately successful. The leading rule for the lawyer, as for the man of every other calling, is diligence. Leave nothing for to-morrow which can be done to-day. Never let your correspondence fall behind. Whatever piece of business you have in hand, before stopping, do all the labor pertaining to it which can then be done.…

Extemporaneous speaking should be practised and cultivated. It is the lawyer’s avenue to the public. However able and faithful he may be in other respects, people are slow to bring him business if he cannot make a speech. And yet there is not a more fatal error to young lawyers than relying too much on speech-making. If any one, upon his rare powers of speaking, shall claim an exemption from the drudgery of the law, his case is a failure in advance.

Discourage litigation. Persuade your neighbors to compromise whenever you can. Point out to them how the nominal winner is often a real loser—in fees, expenses, and waste of time. As a peacemaker the lawyer has a superior opportunity of being a good man. There will still be business enough.

Never stir up litigation. A worse man can scarcely be found than one who does this. Who can be more nearly a fiend than he who habitually overhauls the register of deeds in search of defects in titles, whereon to stir up strife, and put money in his pocket? A moral tone ought to be infused into the profession which should drive such men out of it.

The matter of fees is important, far beyond the mere question of bread and butter involved. Properly attended to, fuller justice is done to both lawyer and client. An exorbitant fee should never be claimed. As a general rule never take your whole fee in advance, nor any more than a small retainer. When fully paid beforehand, you are more than a common mortal if you can feel the same interest in the case, as if something was still in prospect for you, as well as for your client. And when you lack interest in the case the job will very likely lack skill and diligence in the performance. Settle the amount of fee and take a note in advance. Then you will feel that you are working for something, and you are sure to do your work faithfully and well. Never sell a fee note—at least not before the consideration service is performed. It leads to negligence and dishonesty—negligence by losing interest in the case, and dishonesty in refusing to refund when you have allowed the consideration to fail.

There is a vague popular belief that lawyers are necessarily dishonest. I say vague, because when we consider to what extent confidence and honors are reposed in and conferred upon lawyers by the people, it appears improbable that their impression of dishonesty is very distinct and vivid. Yet the impression is common, almost universal. Let no young man choosing the law for a calling for a moment yield to the popular belief—resolve to be honest at all events; and if in your own judgment you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to be honest without being a lawyer. Choose some other occupation, rather than one in the choosing of which you do, in advance, consent to be a knave.