Ranking

#13 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

“I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, January 26, 1863

The Lincoln Log, January 26, 1863

Image Gallery

- Letter to Joseph Hooker

- Joseph Hooker

- Lincoln in 1862

- Hooker and staff

Close Readings

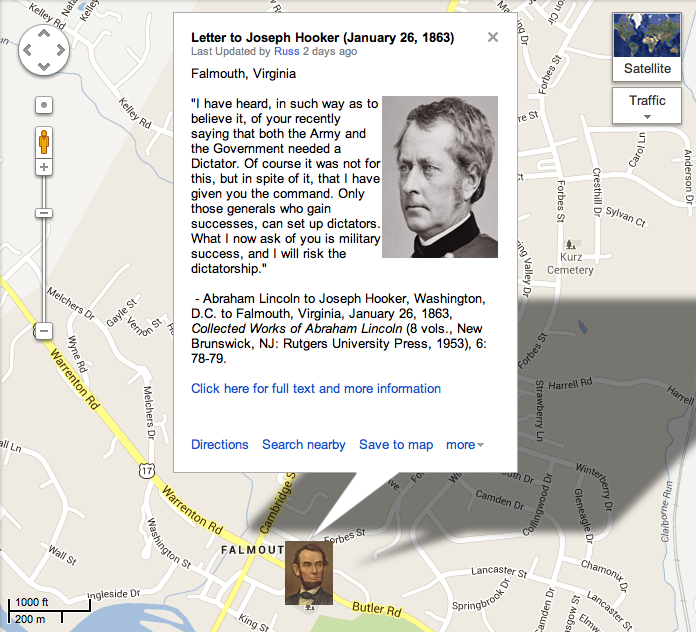

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Noah Brooks quoting Joseph Hooker about Jan. 26 letter

The New York Herald, “The New Commander of the Army of the Potomac,” January 27, 1863

Abraham Lincoln to Joseph Hooker, June 10, 1863

How Historians Interpret

“In naming Hooker, Lincoln read aloud to that general one of his most eloquent letters, a document illustrative of his deep paternal streak. Like a wise, benevolent father, he praised Hooker while gently chastising him for insubordination toward superior officers … Hooker thought it was ‘just such a letter as a father might write to a son. It is a beautiful letter, and although I think he was harder on me than I deserved, I will say that I love the man who wrote it.’ (As John G. Nicolay remarked, ‘it would be difficult to find a severer piece of friendly criticism.’) Boastfully, Hooker told some fellow officers: ‘After I have been in Richmond I shall have the letter published in the newspapers. It will be amusing.”

“Rather uncertainly Lincoln turned to Joseph Hooker. The general had some decided negatives. He was known to be a hard drinker. He had been outspoken almost to the point of insubordination in his criticisms of Burnside’s incompetence, and he let it be known that he viewed the President and the government at Washington as ‘imbecile and played out.’ ‘Nothing would go right,’ he told a newspaper reporter, ‘until we had a dictator, and the sooner the better.’ But the handsome, florid-faced general had performed valiantly in nearly all the major engagements of the Peninsula campaign and at Antietam, where he had been wounded, and his aggressive spirit earned him the sobriquet ‘Fighting Joe.’ Lincoln decided to take a chance on him. Calling Hooker to the White House, he gave the general a carefully composed private letter, which commended his bravery, his military skill, and his confidence in himself. At the same time, he told Hooker, ‘there are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you.’ He lamented Hooker’s efforts to undermine confidence in Burnside and mentioned his ‘recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator.’ … The appointment of Hooker, which was generally well received in the North, relieved some of the immediate pressure on the President. Everybody understood that the new commander would require some time to reorganize the Army of the Potomac and to raise the spirits of the demoralized soldiers. The President could, for the moment, turn his attention to other problems.”

— David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 411-412

Further Reading

Searchable Text