Ranking

#16 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

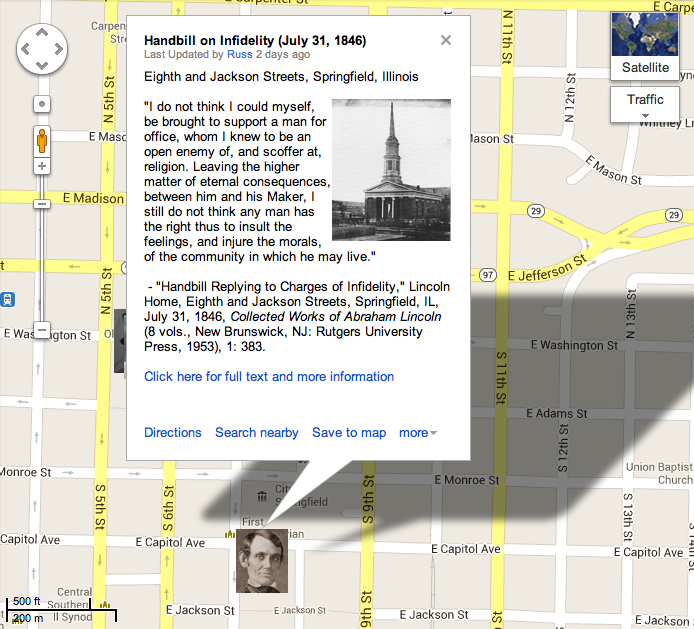

Context. In the summer of 1846, Abraham Lincoln was a Whig candidate for a seat in the US Congress. He was competing against Democratic nominee Peter Cartwright, a well-known Methodist minister who had been one of the earlier settlers of Sangamon County. Despite national attention on the Mexican War, this local race seemed to focus on more personal issues, such as Lincoln’s apparently unorthodox religious beliefs. In this handbill, distributed to voters and published in local newspapers (both before and AFTER the election, at Lincoln’s insistence), candidate Lincoln denied that he was an “open scoffer at Christianity” but admitted that he was not a church member and that he had once argued privately for a kind of deistic fatalism, what he called the “Doctrine of Necessity.” The explosive charges did not prevent Lincoln from defeating Cartwright and securing a term in Congress. (By Matthew Pinsker)

“A charge having got into circulation….”

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, July 31, 1846

Image Gallery

- Lincoln in 1846

- Lincoln’s house

- Peter Cartwright

- Central Illinois

Close Readings

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Handbill on Infidelity (1846) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Abraham Lincoln to Allen N. Ford, Springfield, August 11, 1846

Autobiography of Peter Cartwright (1856)

How Historians Interpret

“This statement appeared less than forthcoming to some residents of the Seventh District. One of them said of Lincoln’s ‘lawyer like declaration’ that in ‘war, politics and religion, a ruse is admissible.’ In this document, Lincoln seemed to make two different claims: that he never believed in infidel doctrines, and that he never publicly espoused them. If the former were true, the latter would be superfluous; if the former were untrue, the latter would be irrelevant. Moreover, his reference to the doctrine of necessity was a dodge, for he was accused of infidelity, not fatalism. In addition, his assertion that he had ‘never denied the truth of the Scriptures’ is belied by the testimony of friends, as is the implication that he was skeptical only in his early years. After moving to Springfield in 1837, Lincoln continued expressing the unorthodox views he had proclaimed in New Salem.”

“Lincoln’s Democratic opponent was Peter Cartwright, the celebrated Methodist circuit rider, famed alike for his muscular Christianity and for his devotion to Jacksonian principles. Though Cartwright was personally popular, he was not an effective political campaigner, and his contest with Lincoln stirred little enthusiasm among voters. Indeed, there was so little interest in the campaign that newspapers only occasionally reported public appearances by either candidate and gave no extended accounts for their speeches. Toward the end of the campaign, growing desperate, Cartwright, in the words of one Whig, ‘sneaked through this part of the district after Lincoln, and grossly misinterpreted him’ by asserting that he was an infidel. Troubled that this accusation, which was similar to charges that had been raised in previous elections, might succeed in ‘deceiving some honest men,’ especially in the northern counties of the district where he was less well known, Lincoln published a little handbill answering Cartwright’s charges . . . Cartwright’s charge obviously had little effect. On August 3 the voters of the Seventh District elected Lincoln by an unprecedented majority.”

—David Hebert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 114

“In all except the most confidential company, Lincoln preferred not to talk about religion at all. And the more social and political prominence he acquired (or, in less friendly terms, the more he identified with the Whig Junto), the less ‘enthusiastic’ he allowed himself to be ‘in his infidelity.’ James Matheny noted that ‘as he grew older he grew more discrete—didn’t talk much before Strangers about his religion.’ And he would not have in 1846, either, if his Democratic opponent in the Seventh District congressional race had not decided to make an issue of it . . . Nothing better illustrates just how sensitive Lincoln was about discussions of his ‘infidelity’ than his decision on July 31, 1846, less than a week before the election, to issue a public handbill, replying to Cartwright’s charges . . . It [the handbill] was clearly aimed at damping down Cartwright’s ‘whispering’ without trying to pretend that the ‘whispers’ were entirely untrue.”

—Allen Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1999), 116-7

Further Reading

Searchable Text