The reaction to President Obama’s appearance on Between Two Ferns was swift. 32,000 viewers clicked through the video to HealthCare.gov, more than 1,000 tweeted about the segment, and health plan enrollments skyrocketed as the final deadlines approached. None of those suggestions of effectiveness, however, prevented Fox News host Bill O’Reilly from leveling a pretty tough criticism. O’Reilly was blunt and authoritative as always: “all I can tell you is Abe Lincoln wouldn’t have done it.”

The reaction to President Obama’s appearance on Between Two Ferns was swift. 32,000 viewers clicked through the video to HealthCare.gov, more than 1,000 tweeted about the segment, and health plan enrollments skyrocketed as the final deadlines approached. None of those suggestions of effectiveness, however, prevented Fox News host Bill O’Reilly from leveling a pretty tough criticism. O’Reilly was blunt and authoritative as always: “all I can tell you is Abe Lincoln wouldn’t have done it.”

Putting aside the question of whether Abraham Lincoln really would have refused to appear on Between Two Ferns, there are a few important issues to consider when comparing President Obama’s stated goals for his unusual interview with the political experiences of President Lincoln. Those comparisons can begin with O’Reilly’s criticism itself, which actually sounds quite similar to some 19th-century commentaries about Lincoln. Ralph Waldo Emerson, writing in his diary, once accused Lincoln of “cheapening himself” as a public figure, noting that:

“He will not walk dignifiedly through the traditional part of the President of America, but will pop out his head at each railroad station and make a little speech, get into an argument with Judge A and Squire B, he will write letters to Horace Greeley, and any editor or reporter…or saucy party committee that writes to him…”

The letters Emerson was referring to – public letters – particularly rankled some 19th-century American opinion leaders. Douglas Wilson, a historian and two-time Lincoln Prize winner, notes in Lincoln’s Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (2007), that Lincoln’s unprecedented use of public letters was viewed by some as “undignified.” Lincoln was about as compelled by that criticism then as President Obama is now. The two presidents seem to share a desire to avoid, in Obama’s words, the “Washington echo chamber.” They both sought out mediums and messages that would do just that, resonating with everyday people and conveying a highly personal touch. In attempting to quench the desire to directly connect, Obama has the internet and Lincoln had the public letter. Beginning in 1862 with his letter to Horace Greeley and continuing in 1863 with longer missives to Erastus Corning and James Conkling, Lincoln shaped popular opinion and shared his views with constituents by “corresponding” through newspapers. His messages, on slavery, emancipation, and federal power, were circulated and read widely. The Conkling letter, which we recently annotated on Poetry Genius, includes Lincoln’s famous line stating that, “there can be no appeal from the ballot to the bullet,” and employs shifts in tone and argument to convince a broad swath of the political spectrum about the wisdom of the Emancipation Proclamation. Wilson, again in Lincoln’s Sword, argues that these public letters demonstrably helped improve the president’s popularity and support for the Union cause.

A public letter to the editor of a newspaper or a political leader is a long way, however, from appearing on an internet comedy show hosted by the actor from Hangover 3. And it is worth noting that Lincoln’s public letters rarely employed humor in any substantive form. He was far from unfunny, though; in fact, in connecting with political leaders and laymen alike, Lincoln employed a similarly eclectic sense of humor that was also subject to criticism. In fact, some public figures attacked Lincoln for his humor in a way that will sound familiar to keen observers of the Between Two Ferns debate. Historian Louis Masur has a great short post (“Lincoln Tells a Story”) at the New York Times Disunion series which details both some of Lincoln’s story-telling habits and the uneven reaction. He quotes Richard Henry Dana, a prominent nineteenth-century writer and attorney, who spoke for many New Englanders when he complained during the war that Lincoln “does not act or talk or feel like the ruler of a great empire in a great crisis.” In a scholarly article titled Lincoln’s Humor: An Analysis, Benjamin Thomas fully chronicles the 16th President’s flair for pith, wit, and tall tales. The article is a treasure trove of Lincolniana, ranging from yarns and one-liners to comic biography and commentary on 19th-century humor. Thomas notes that according to Henry C. Whitney, one of Lincoln’s friends from his Illinois years, “any remark, any incident brought from [Lincoln] an appropriate tale…he saw ludicrous elements in everything.” Thomas’s analysis is instructive, at least in one sense. After all, it is hard to imagine that the man who asked whether a Nebraska river named Weeping Water was called Minneboohoo by the Indians (“because Minnehaha is Laughing Water in their language”) would not have enjoyed at least some of Two Ferns banter about strange spider bites and 800-ounce babies.

In a scholarly article titled Lincoln’s Humor: An Analysis, Benjamin Thomas fully chronicles the 16th President’s flair for pith, wit, and tall tales. The article is a treasure trove of Lincolniana, ranging from yarns and one-liners to comic biography and commentary on 19th-century humor. Thomas notes that according to Henry C. Whitney, one of Lincoln’s friends from his Illinois years, “any remark, any incident brought from [Lincoln] an appropriate tale…he saw ludicrous elements in everything.” Thomas’s analysis is instructive, at least in one sense. After all, it is hard to imagine that the man who asked whether a Nebraska river named Weeping Water was called Minneboohoo by the Indians (“because Minnehaha is Laughing Water in their language”) would not have enjoyed at least some of Two Ferns banter about strange spider bites and 800-ounce babies.

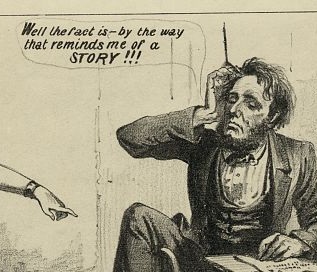

Lincoln didn’t lampoon Nebraska’s American Indian population in a public speeches or documents, though. Much of the humor Thomas describes appears to be drawn from personal interactions described in diary entries or recollections. The historian argues that after 1854, Lincoln’s public persona became more serious. O’Reilly, who has written a book on Lincoln, might have this fact in mind when he criticizes President Obama. O’Reilly could argue that as Lincoln ascended to power, he acknowledged the seriousness of the moment and changed the tone of his rhetoric. It is true that Lincoln’s rhetoric during the late 1850s and 1860s lacks some of the Springfield lawyer’s earlier folksy-funny style, but this shift did not help him shed a humorous public countenance. In the House Divided research engine, we feature several anti-Lincoln cartoons, like the one detailed above (“Columbia Demands Her Children”), which take him to task for not being serious enough (See also “Running the Machine” and “The Abolition Catastrophe” –all from the 1864 reelection campaign). These images seem to indicate that there were personal and political dimensions to Lincoln’s humor that extended well into the years of his presidency.

It is never simple to compare different moments in history, but what is at the heart of President Obama’s appearance on Between Two Ferns – the desire to connect directly to citizens and convey a persuasive message – is familiar to all who study the history of American politics. Lincoln shared President Obama’s interest in communicating directly with the American public, and doing so in a way that was original and compelling. While his humor and desire to connect with voters do not converge in his public letters, Lincoln used both humor and public correspondence in the same way that President Obama used Between Two Ferns: to develop a personal rapport with constituents, and bolster their support for a national agenda. Few things are more presidential than that.

Michael Lind

Michael Lind Richard Norton Smith might beg to disagree. Smith is one of the nation’s most prominent presidential historians. Currently a history faculty member at

Richard Norton Smith might beg to disagree. Smith is one of the nation’s most prominent presidential historians. Currently a history faculty member at  Like Richard Norton Smith, Craig Symonds tries to embody the classic scholarly caution about applying the past the to the present. Symonds taught for years in the History Department at the US Naval Academy. In fact, Symonds was the guy whom Harrison Ford “shadowed” in 1991 while he was studying up for his role as professor / spy Jack Ryan in the “The Patriot Games.” Symonds has authored or edited more than 20 history books, mostly on the Civil War or US naval history. He won the 2009 Lincoln Prize for his book,

Like Richard Norton Smith, Craig Symonds tries to embody the classic scholarly caution about applying the past the to the present. Symonds taught for years in the History Department at the US Naval Academy. In fact, Symonds was the guy whom Harrison Ford “shadowed” in 1991 while he was studying up for his role as professor / spy Jack Ryan in the “The Patriot Games.” Symonds has authored or edited more than 20 history books, mostly on the Civil War or US naval history. He won the 2009 Lincoln Prize for his book,