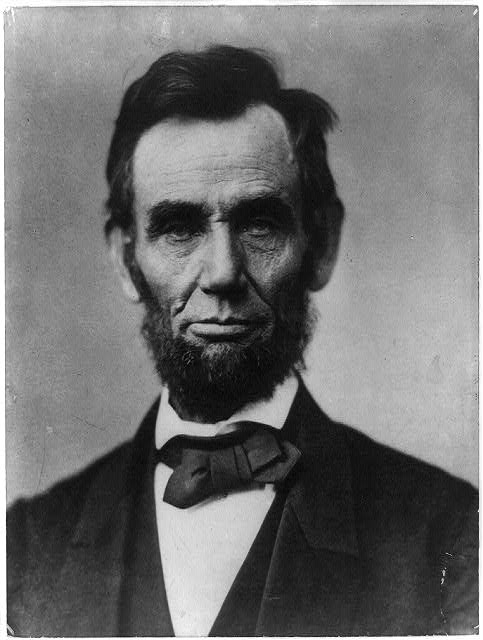

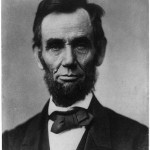

On Tuesday evening, July 7, 1863, Abraham Lincoln responded to a “serenade” from a crowd outside the White House celebrating the wonderful news received in Washington earlier that day that Vicksburg had finally surrendered to Union forces (actually on the Fourth of July, Independence Day). Speaking extemporaneously, the president struggled to find the right words to put the twin victories –Vicksburg and Gettysburg– into context.

On Tuesday evening, July 7, 1863, Abraham Lincoln responded to a “serenade” from a crowd outside the White House celebrating the wonderful news received in Washington earlier that day that Vicksburg had finally surrendered to Union forces (actually on the Fourth of July, Independence Day). Speaking extemporaneously, the president struggled to find the right words to put the twin victories –Vicksburg and Gettysburg– into context.

How long ago is it? –eighty odd years– since on the Fourth of July for the first time in the history of the world a nation by its representatives assembled and declared as a self-evident truth that “all men are created equal.”

Ever since, many Lincoln scholars have noted –though not nearly enough classroom teachers have realized– that this “Response to a Serenade” from July 7, 1863 stands as an especially compelling “first draft” for the Gettysburg Address, whose famous opening lines delivered just over four months later on November 19, 1863 clearly owed their origins to Lincoln’s desire to revise and improve what for him had been a somewhat awkward initial effort:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

But there’s even more to this “first draft” story than most Lincoln scholars have acknowledged. It appears very likely that Lincoln was working at least in part from another man’s text as he contemplated how to answer that boisterous serenade on Tuesday evening, July 7. Sometime the night before or earlier that day, the president probably read and was inspired by what historian Harold Holzer is now calling “the greatest piece of war reporting ever,” a stunning dispatch from Gettysburg written by a New York Times correspondent whose eldest son had died tragically on that first day of the great battle.

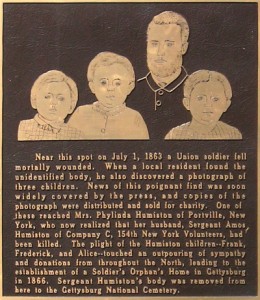

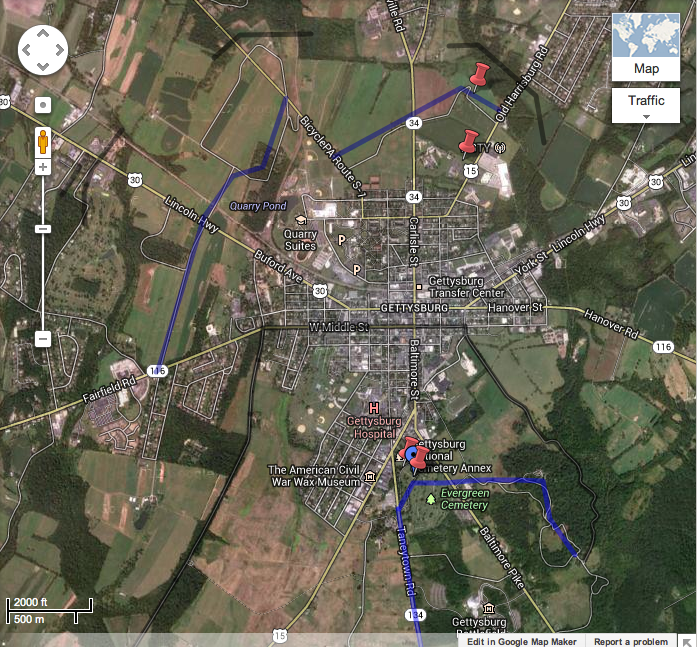

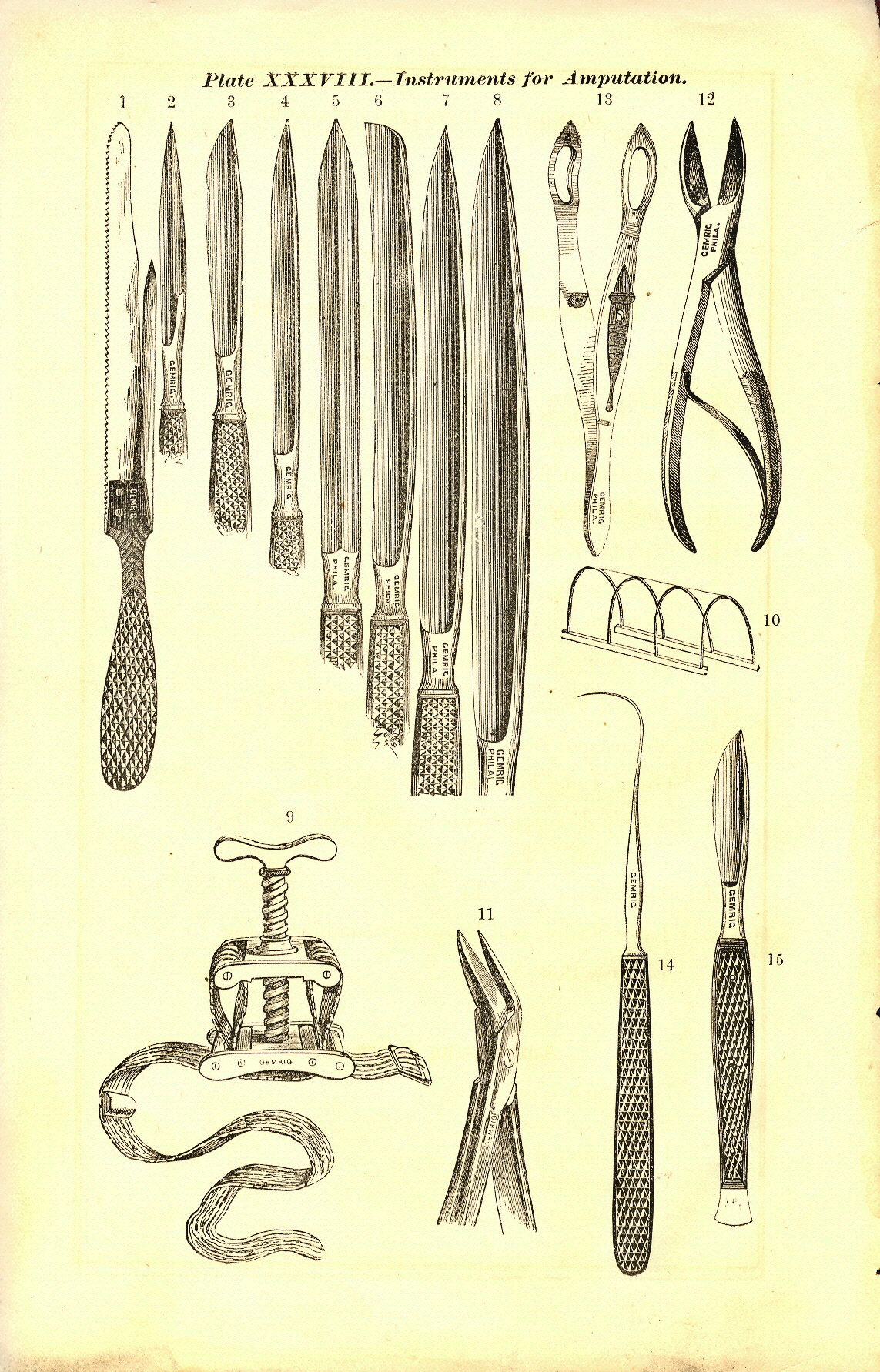

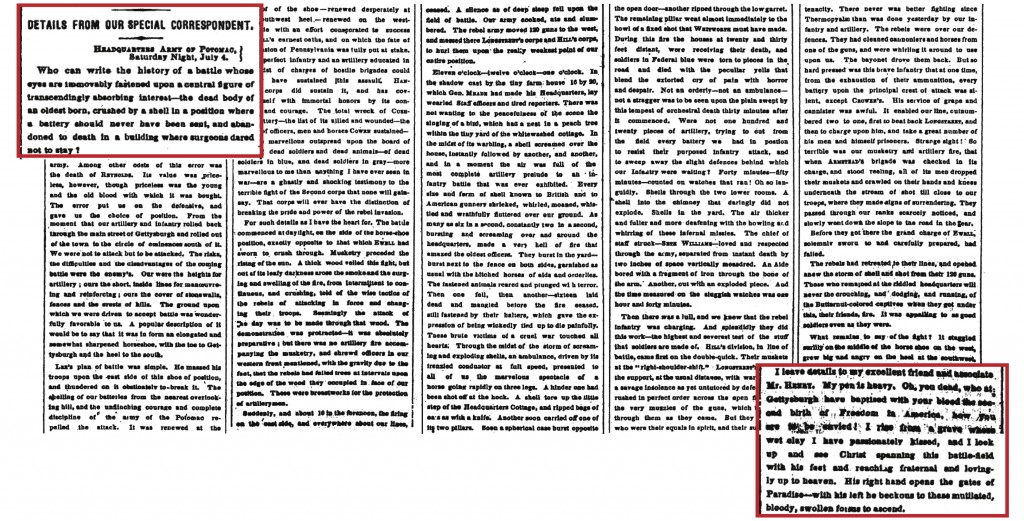

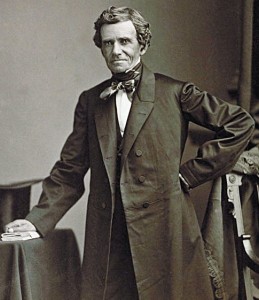

The story of the reporter, Samuel Wilkeson, and his son, Bayard, is also reasonably well known to Civil War scholars and Gettysburg buffs, but nonetheless remains absent from most American textbooks and classroom discussions. Yet the reason why Holzer is featuring it in his next book (on Lincoln and the press) and why we have been focusing so much attention on it here at House Divided (see our earlier posts here and here), is because of the many layers of human drama involved. Lt. Bayard Wilkeson was 19-years-old when an artillery shell nearly severed his leg around mid-day on July 1, 1863 north of the town , along what is now known as Barlow’s Knoll (see image above). The brave young man was then forced to amputate his own leg before he ultimately died from shock that evening while in Confederate custody. Meanwhile, his father Samuel had been trying to rush up to the battlefield to report on General Meade and the Army of the Potomac as they entered into combat with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Sam Wilkeson spent two anxious days reporting from Meade’s headquarters and wondering what had happened to his son, knowing only that Bayard had been wounded and captured. Eventually, Wilkeson found his dead boy on Saturday evening, July 4, and wrote his lead dispatch for the New York Times with these memorable words:

The story of the reporter, Samuel Wilkeson, and his son, Bayard, is also reasonably well known to Civil War scholars and Gettysburg buffs, but nonetheless remains absent from most American textbooks and classroom discussions. Yet the reason why Holzer is featuring it in his next book (on Lincoln and the press) and why we have been focusing so much attention on it here at House Divided (see our earlier posts here and here), is because of the many layers of human drama involved. Lt. Bayard Wilkeson was 19-years-old when an artillery shell nearly severed his leg around mid-day on July 1, 1863 north of the town , along what is now known as Barlow’s Knoll (see image above). The brave young man was then forced to amputate his own leg before he ultimately died from shock that evening while in Confederate custody. Meanwhile, his father Samuel had been trying to rush up to the battlefield to report on General Meade and the Army of the Potomac as they entered into combat with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Sam Wilkeson spent two anxious days reporting from Meade’s headquarters and wondering what had happened to his son, knowing only that Bayard had been wounded and captured. Eventually, Wilkeson found his dead boy on Saturday evening, July 4, and wrote his lead dispatch for the New York Times with these memorable words:

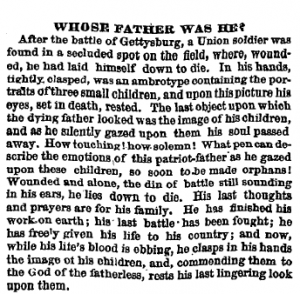

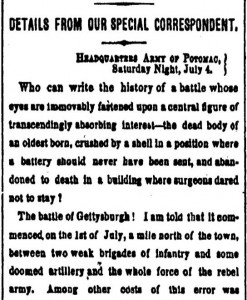

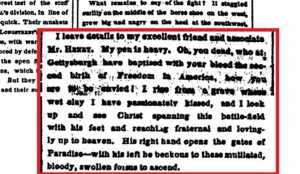

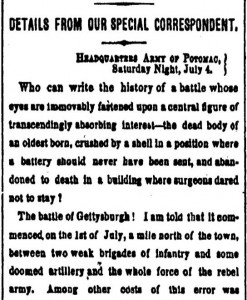

Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest -the dead body of an eldest born crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not stay?

Wilkeson then produced a dramatic and detailed account of the battle, which was published on Monday, July 6, 1863, and which he closed in this stirring fashion:

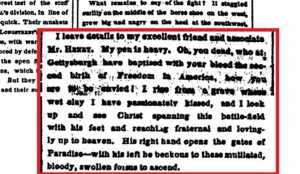

Oh, you dead who at Gettysburg have baptised with your blood a second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied.

To read the full text of Samuel Wilkeson’s article, go to the House Divided research engine, or click here

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.

Yet that is surely too much scholarly caution. Holzer confirms that during the Civil War Lincoln had same day or next day access to the New York Times, and while nobody knows for certain if Lincoln read Wilkeson’s dispatch before he replied to the serenade, there are a handful of good reasons for believing that he did. First, he and his aides knew Sam Wilkeson quite well. The story of Bayard’s death and his father’s dramatic reaction is one that would have transfixed them as it did nearly everybody else in the North. But second, and more important, Lincoln appeared to allude to the episode in his brief remarks on Tuesday evening, July 7:

I would like to speak in terms of praise due to the many brave officers and soldiers who have fought in the cause of the Union and liberties of the country from the beginning of the war … [but] I dislike to mention the name of one single officer lest I might do wrong to those I might forget. Recent events bring up glorious names, and particularly prominent ones, but these I will not mention.

Perhaps the president was referring here to General John F. Reynolds or other tragic losses from the battle, but I believe this is a direct reference to the Wilkeson sacrifice. One certainly cannot ignore the fact that the sentiment Lincoln offered here of not mentioning names later became the guiding principle of his Gettysburg Address. On November 19, 1863, Lincoln mentioned nobody by name. He offered no specific details. Ordinarily, we warn students against abstractions and encourage them to be as concrete as possible in their writing. Lincoln was anything but specific in his Gettysburg Address. However, like many great writers, he was thoroughly evocative. Those last lines of the Address were especially evocative for nineteenth-century audiences, not only paraphrasing Daniel Webster’s famous Second Reply to Hayne (“It is, Sir, the people’s Constitution, the people’s Government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people” (January 26-27, 1830), but also –I would argue– paraphrasing the “greatest piece of war reporting ever” from Samuel Wilkeson. Even if we will never know the full truth behind the “first draft” of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, I hope more teachers see the value in bringing up this poignant and powerful story in their classrooms and letting students decide for themselves.

Stories like this one and many others like it that help bring to life Lincoln and the Civil War provide the animating spirit behind our latest project –the creation of a new multi-media edition of Lincoln’s Writings that we are launching on July 7, 2013 (marking the 150th anniversary of Lincon’s “first draft” of the Gettysburg Address). The multi-media edition will include 150 of Lincoln’s documents that I have dubbed his “most teachable.” The pages of this site will be populated with all kinds of digital tools, such as audio recordings of the documents in Lincoln’s voice (by Dickinson College theatre professor Todd Wronski), interactive maps, clickable word clouds, and videos of me conducting close readings of the top 25 key documents (starting with the Gettysburg Address, ranked naturally as #1). This has been a big project with excellent work from many people, most notably House Divided co-founder John Osborne, our technical director Ryan Burke, and Dickinson College undergraduates Russ Allen and Leah Miller. The multi-media project itself will then become the focal point of the “Understanding Lincoln” open, online course that we are currently preparing to offer this summer and fall in partnership with the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Students in that course will work toward building out the Lincoln’s Writings website with an anticipated first-stage completion date of November 19, 2013 (not coincidentally marking the 150th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address). Registration for that course closes on July 19, 2013. A full credit graduate section is available and designed especially for K-12 educators. Please check out the new Lincoln’s Writings website and watch specially designed close reading videos, like the one below, with me explaining Lincoln’s writing process for his Gettysburg speech and the Wilkeson connection to the Address:

Matthew Pinsker: Understanding Lincoln: Gettysburg Address (1863) from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

To honor Lincoln’s 205th birthday, we are tweeting out the top ten Lincoln resources from House Divided. But here is the full list:

To honor Lincoln’s 205th birthday, we are tweeting out the top ten Lincoln resources from House Divided. But here is the full list:

Michael Lind

Michael Lind Richard Norton Smith might beg to disagree. Smith is one of the nation’s most prominent presidential historians. Currently a history faculty member at

Richard Norton Smith might beg to disagree. Smith is one of the nation’s most prominent presidential historians. Currently a history faculty member at  Like Richard Norton Smith, Craig Symonds tries to embody the classic scholarly caution about applying the past the to the present. Symonds taught for years in the History Department at the US Naval Academy. In fact, Symonds was the guy whom Harrison Ford “shadowed” in 1991 while he was studying up for his role as professor / spy Jack Ryan in the “The Patriot Games.” Symonds has authored or edited more than 20 history books, mostly on the Civil War or US naval history. He won the 2009 Lincoln Prize for his book,

Like Richard Norton Smith, Craig Symonds tries to embody the classic scholarly caution about applying the past the to the present. Symonds taught for years in the History Department at the US Naval Academy. In fact, Symonds was the guy whom Harrison Ford “shadowed” in 1991 while he was studying up for his role as professor / spy Jack Ryan in the “The Patriot Games.” Symonds has authored or edited more than 20 history books, mostly on the Civil War or US naval history. He won the 2009 Lincoln Prize for his book,

The story of the reporter,

The story of the reporter,

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.

This story raises a profound question: was Wilkeson’s “second birth of Freedom in America” a line that Lincoln was recalling and intentionally evoking when he closed his own Address at Gettysburg on November 19 with the phrase, “a new birth of freedom”? The National Park Service displays relics from Bayard Wilkeson’s death, including the sash he used as a tourniquet, and they provide a text panel showing the opening of his father’s famous dispatch (later turned into a pamphlet, Sam Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture of Gettysburg), but they refrain from making any direct connections between Wilkeson’s account and Lincoln’s address. Most scholars have so far been equally reticent about making that interpretive leap.