As a summer intern with the House Divided Project of Dickinson College, I’ve been assigned the task of coming up with a lesson plan for the incredible story of how the tragic death of Bayard Wilkeson during the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg touched our nation. Make sure to read the full story contained within one of our previous posts, or take the virtual “teacher’s tour” of Gettysburg to find out more.

The (Brief) Story:

On the first day of the Gettysburg campaign (1 July 1863), nineteen-year-old Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson was severely wounded in the leg at Barlow’s Knoll. Medics carried him off the battlefield to the Adams County Alms House where they attempted to amputate his mangled limb. Unfortunately, the Alms House was overrun by Confederate troops and the surgeons fled, leaving young Wilkeson to amputate his own leg with his own knife, from which he died of shock several hours later.

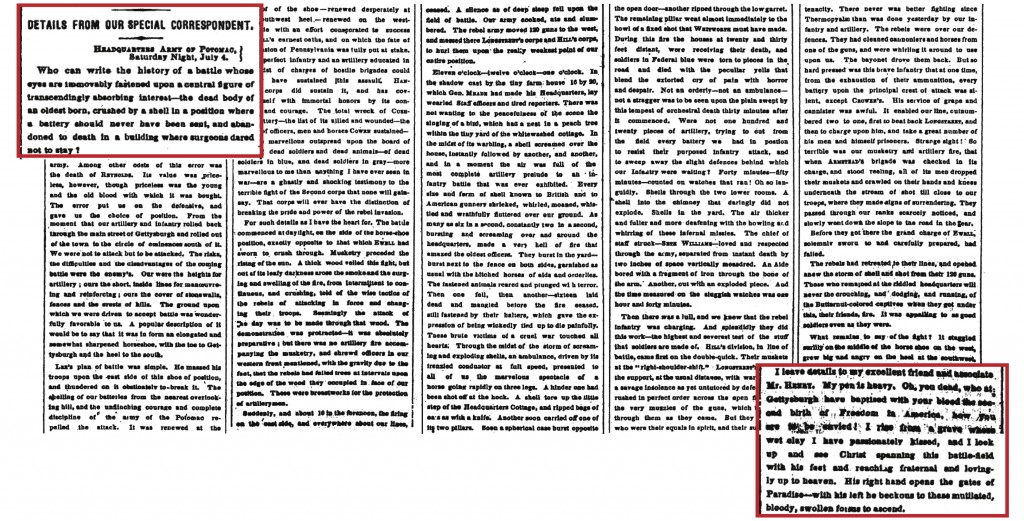

His father, Samuel Wilkeson, was a war correspondent for the New York Times, and he arrived at Gettysburg on 2 July and began to look for his son. He found Bayard’s body in the Alms House a few days later, and wrote a report of the campaign which was featured in the Times on 6 June. According to Professor Matthew Pinsker, the director of the House Divided Project, Wilkeson’s concluding words, “Oh, you dead, who at Gettysburgh have baptised with your blood the second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied!” may have influenced the conclusion of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Why Teach It:

The story of Bayard and Samuel Wilkeson is a small but powerful episode of the Gettysburg campaign not taught in most textbooks. It emphasizes the emotional side of the battle, the side that tore apart families and took the lives of young men. Bayard Wilkeson’s young age will allow your students to identify more easily with the story, imagining themselves in his position as he fought courageously, was severely wounded, and desperately mutilated himself in an attempt to save his own life. The New York Times article written by Samuel Wilkeson conveys the emotional intensity of a father who had lost his son to what he deemed a noble cause, and the conflict of interest there. Most importantly, Samuel Wilkeson was a top war correspondent for the New York Times; his story was first published in the Times but later was reproduced as a pamphlet entitled, “Samuel Wilkeson’s Thrilling Word Picture Of Gettysburgh“. Many people would have been familiar with the story, including President Lincoln, who had been friends with the Wilkeson family. Lincoln ended his most famous speech, the Gettysburg address, with these words:

“It is rather for us [the living] to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom…”

which seem to have been directly derived from Wilkeson’s famous article.

Tools for Teaching Bayard Wilkeson:

It could be a means to introduce the topic by discussing the casualties in the Battle of Gettysburg. A great and impacting illustration of the Union casualties is in this diagram of the layout of the Gettysburg Civil War Cemetery; your students can see in picture-form which states lost the most amount of men, and how many men were buried unidentified. The largest section of graves, on the outer edge of the semicircle, belongs to New York, where Bayard Wilkeson was born. The second-worst case was Pennsylvania’s. From here you could lead into the story of Bayard Wilkeson, whose death represented so much for the American people, and Lincoln himself.

A great and impacting illustration of the Union casualties is in this diagram of the layout of the Gettysburg Civil War Cemetery; your students can see in picture-form which states lost the most amount of men, and how many men were buried unidentified. The largest section of graves, on the outer edge of the semicircle, belongs to New York, where Bayard Wilkeson was born. The second-worst case was Pennsylvania’s. From here you could lead into the story of Bayard Wilkeson, whose death represented so much for the American people, and Lincoln himself.

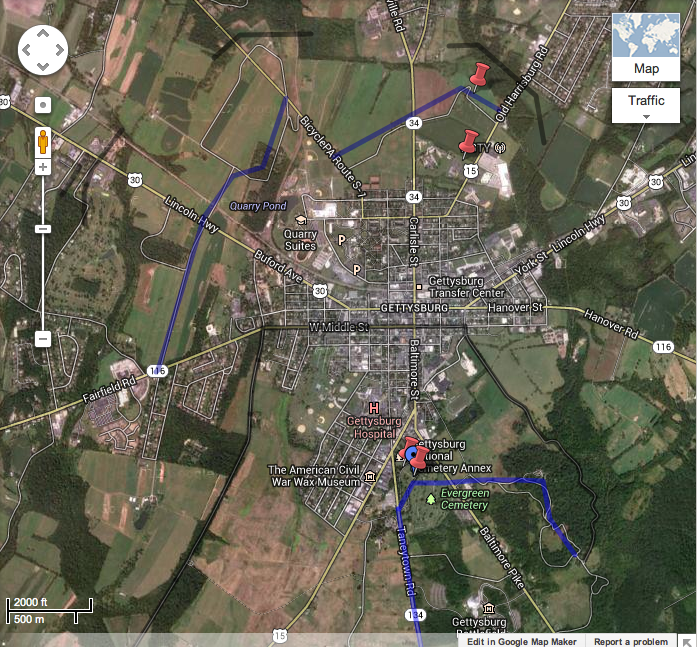

Below is a simple interactive map I’ve created for the story using GoogleMaps. It could be a helpful tool for your students to see the Confederate and Union lines across the battlefield and the modern-day town of Gettysburg. Important takeaways include the distance between where Bayard was injured at Barlow’s Knoll and the Alms House, where he was carried, as well as the proximity of the delivery of the Gettysburg Address, meant to evoke the well-known story of Bayard’s death and emotional memories that accompanied it.

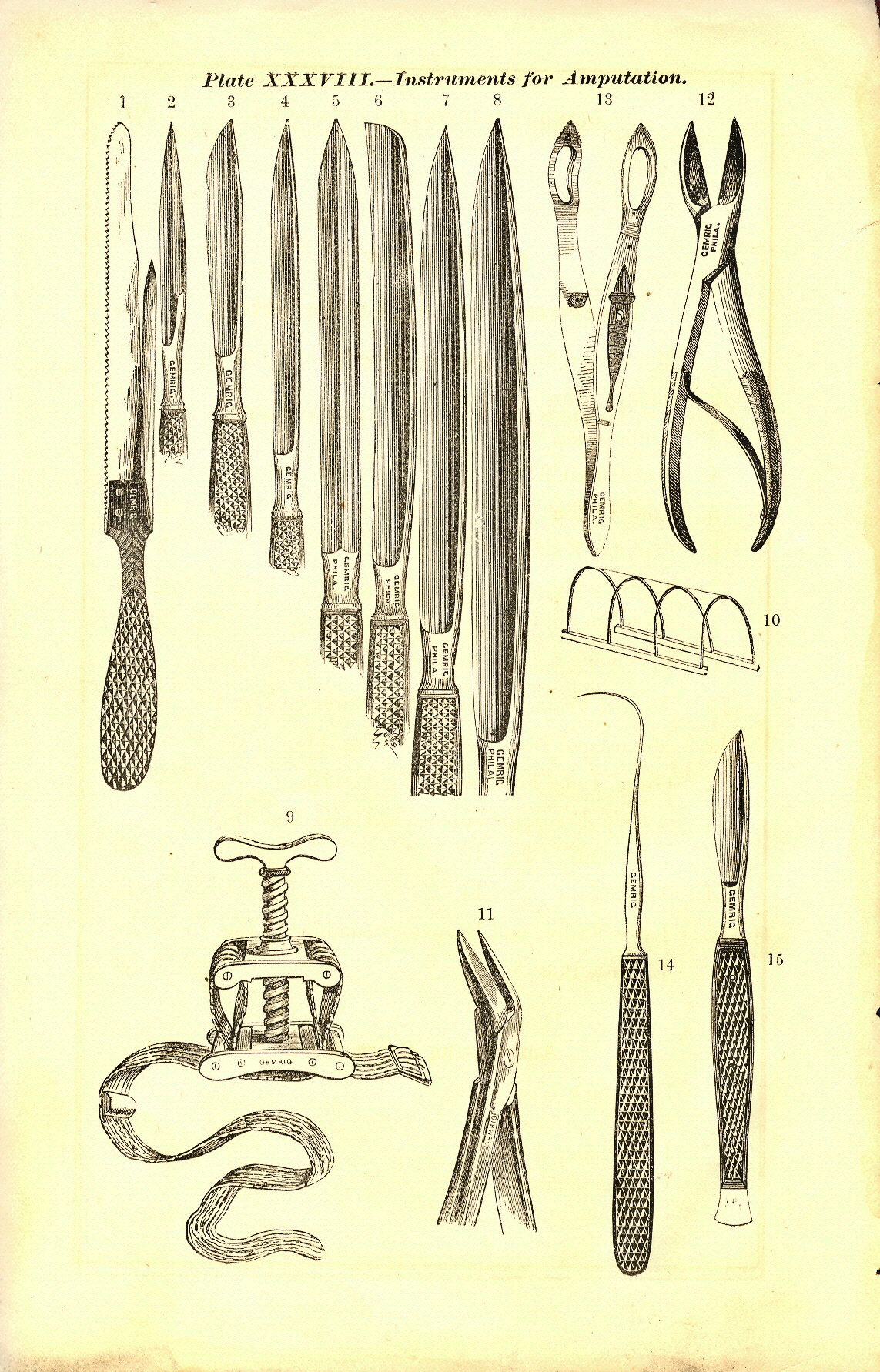

It is too easy to forget that the past was often not at all like the present. To remind your students of this, and to provide helpful context for the story, you could briefly describe Civil War era medicine. For example, here is a link to a site on Civil War era medicine. Take note of the establishment of a system for wounded-soldier evacuation, the techniques for field dressing, and the description of field hospitals. Here is a link to mid-nineteeth century medical equipment, including tools used in the performance of amputation.

It is too easy to forget that the past was often not at all like the present. To remind your students of this, and to provide helpful context for the story, you could briefly describe Civil War era medicine. For example, here is a link to a site on Civil War era medicine. Take note of the establishment of a system for wounded-soldier evacuation, the techniques for field dressing, and the description of field hospitals. Here is a link to mid-nineteeth century medical equipment, including tools used in the performance of amputation.

On the other hand, the Civil War era press was different from our newspapers of today. Most newspapers did not contain images, so stories like Samuel Wilkeson’s were meant to paint a picture of the events at Gettysburg. The Civil War was also the first major war in which families could find out about the death of their loved ones before the war was over (and they just didn’t come home), and newspapers played a critical role in that respect. Here is an article on the conflict between the military and the home front regarding the issue of press censorship in the Civil War.

It would be most useful to show Samuel Wilkeson’s article and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address side by side to show the relationship between the two. Lincoln’s Address, which was meant to evoke sentiment rather than statistics, draws upon the emotional intensity of the Battle of Gettysburg, just as Samuel Wilkeson’s article raved passionately about the loss of his son. It is very important that your students see the connection between Lincoln’s phrase, “It is rather for us [the living] to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom…” evokes Samuel Wilkeson’s phrase, “Oh, you dead, who at Gettysburgh have baptised with your blood the second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied!” (emphases added), including the idea that what the soldiers died for was worth it.

Finally, I’m including a handout created by House Divided director Matthew Pinsker on the Bayard Wilkeson story. It would be useful for your students to have a physical copy to include in their notes.

Related Articles

1 user responded in this post

Thank you for a thoroughly male point of view. Unfortunately you have totally missed any female point of view. The death of a son must have impacted his mother. Interesting Bayard’s mother was the sister of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. That said, Dr Ann Gordon just completed a 30+ year project of amassing Elizabeth’s correspondence. I urge you to research; attempt to find the letter Catherine sent to her sister, Elizabeth, announcing the death of Bayard. What else did she say about war in that letter? Overall, in your “teaching” of the Civil War, where are the voices of women? Submitted by Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s great-great granddaughter

Leave A Reply

Please Note: Comment moderation maybe active so there is no need to resubmit your comments