DATELINE: NOVEMBER 7, 1859, LAGRANGE, MO

Enslaved people escape aboard a small water craft, as depicted in Harper’s Weekly on April 9, 1864. (House Divided Project)

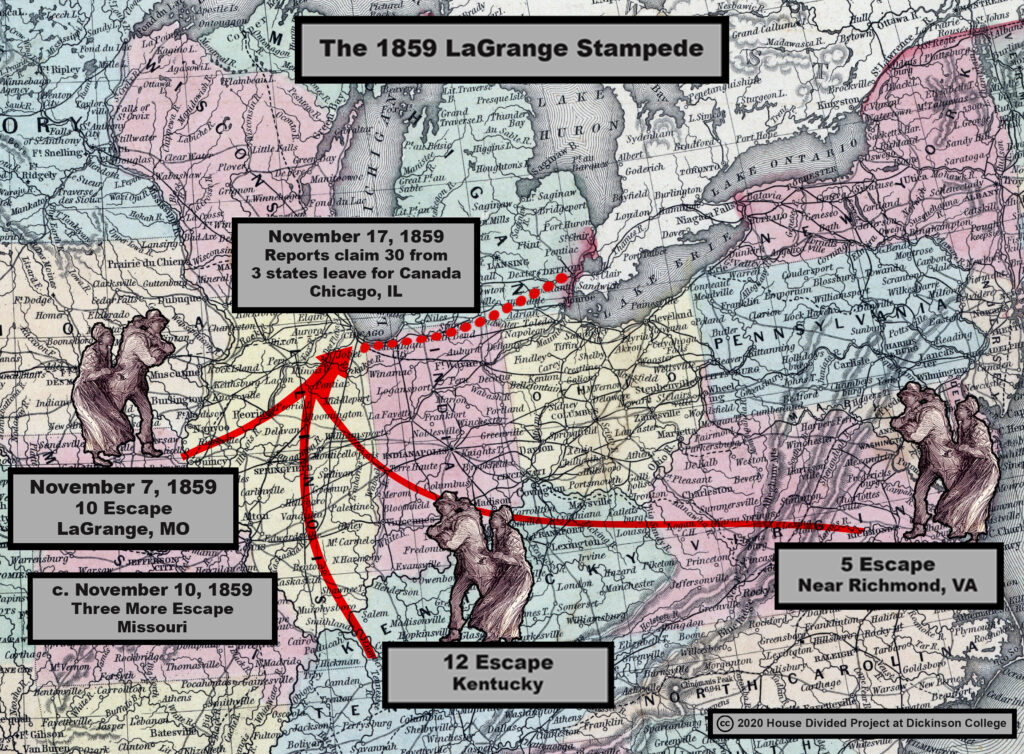

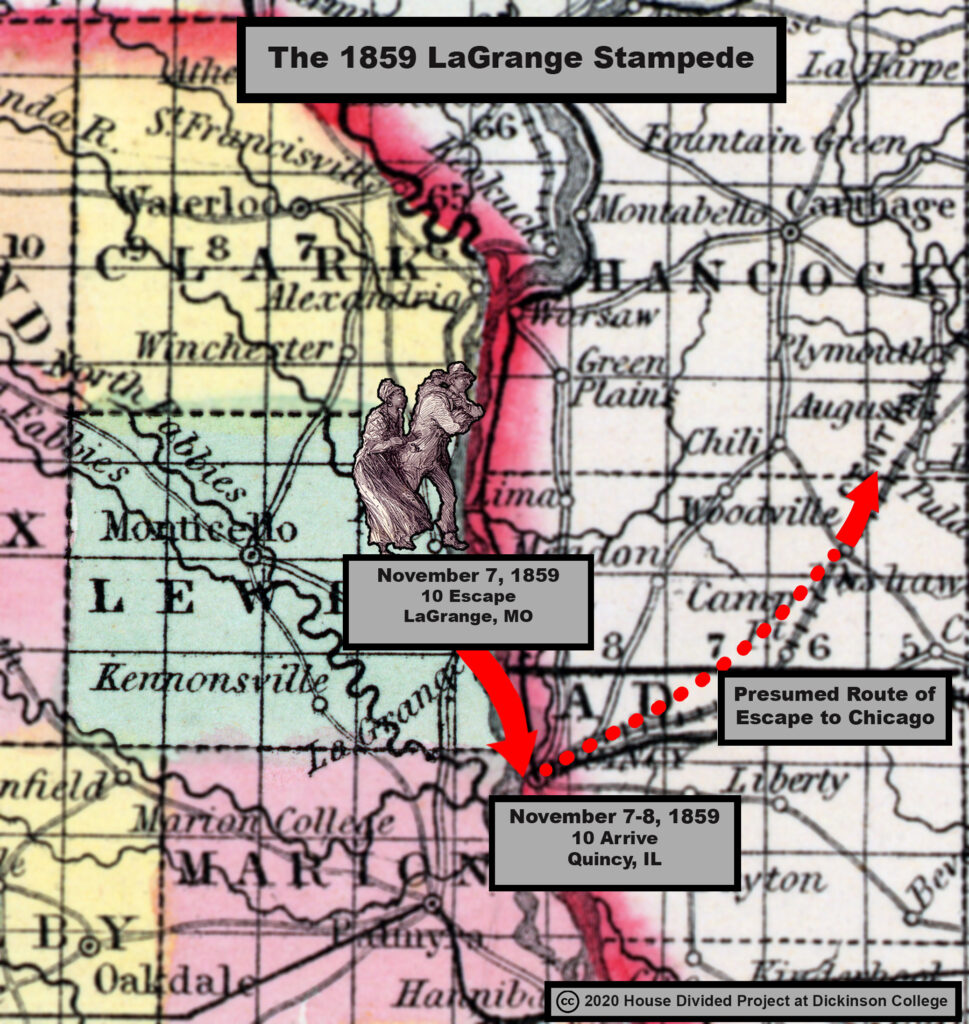

On Monday night, November 7, 1859, ten enslaved people crowded into a stolen flatboat and pushed off into the Mississippi River. Escaping from bondage in the riverside town of LaGrange, Missouri, these five men and five women steered a course by moonlight, local knowledge, and sheer determination, traveling some ten miles southeast to Quincy, Illinois. The next morning, seven slaveholders awoke to discover their “valuable slaves,” worth “not less than $10,000,” suddenly gone, and offered up a hefty $2,650 reward for their recapture. Costly as it was to local slaveholders, it was by no means the first such large escape launched from the vicinity. The town’s newspaper, the LaGrange American, hardly needed to remind readers that this latest episode marked “the third or fourth successful stampede that has taken place from LaGrange in the past three or four months.” Escapes were becoming so common, the paper alleged that “there is a regular underground railroad established from this place to Chicago.” [1] The enslaved men and women who set out upon that “underground railroad” revealed how coordinated group escapes posed a direct threat not only to slaveholders’ bottom line, but to the stability of slavery itself along the Missouri-Illinois border.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

Days after the escape, the LaGrange American described the episode as the most recent “successful stampede” from the region. This report was picked up by several Missouri papers, including the St. Louis News and Glasgow Weekly Times, both of which used the term “stampede.” The brief bulletin published by the St. Louis News attracted national attention, and was widely reprinted by newspapers in Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, Ohio, and Kentucky, under headlines such as “Negro Stampede,” “Stampede of Negroes in Missouri,” and “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County.” [2]

MAIN NARRATIVE

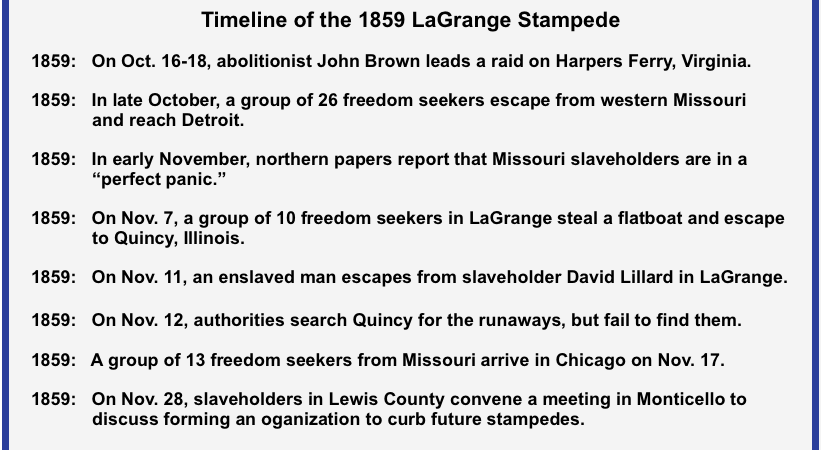

The identities of the ten enslaved Missourians who escaped from LaGrange are unknown, as are the names of the seven slaveholders who laid claim to them. However, it is clear that the LaGrange stampede occurred amid a period of heightened anxieties for Missouri slaveholders. Less than a year earlier in December 1858, abolitionist John Brown had led a daring raid into western Missouri that freed eleven bond people, and in January 1859 his protege John Doy was captured and convicted of “seducing” enslaved Missourians to leave the state. Doy was rescued from prison in July, much to the outrage of proslavery Missourians. Then in mid-October, Brown and an armed group seized control of a federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in an abortive attempt to spark a slave revolt. As the Harpers Ferry raid captivated the nation and fed white southerners’ worst fears, Missouri papers were attentively reporting on the “irrepressible exodus of slaves from the borders of Missouri.” In October, a group of 26 freedom seekers escaped from western Missouri with the aid of antislavery operatives, traveling through Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, and Illinois, eventually arriving in Detroit to considerable fanfare. Although matters seemed to be reaching a crisis point by late 1859, it was by no means the first time that slaveholders in Lewis County had grappled with an “exodus” of enslaved men and women. In fact, the escape from LaGrange occurred ten years to the week after an earlier “stampede” from Lewis County, where more than 30 enslaved people had struck out for freedom only to be subdued following a violent clash with slaveholders. [3]

More than ever before, human property seemed a risky investment in some parts of Missouri, particularly in places like LaGrange, where multiple “stampedes” had already occurred during the fall of 1859. Northern papers commented that “a perfect panic has seized the slaveholders of Missouri,” and the St. Louis Democrat concurred. A free soil press allied with the new antislavery Republican party, the Democrat wanted to wean the state off its dependence on enslaved labor, less out of sympathy for the enslaved than racist motivations to make room for free white labor. So the influential paper recounted the “exodus” of African Americans from the state––both in freedom seekers heading north, and in enslaved people being sold south by slaveholders apprehensive about the growing tide of escapes. Each day witnessed more enslaved Missourians forced aboard steamboats and sold down the river. “A visit to our levee will convince the skeptical of the steady and continual flow of slave property to the South,” the St. Louis organ declared. Some contemporaries referred to this as “the stampede South,” and further evidence that “the State is fast emancipating itself from the incubus of slavery.” [4]

It appears the ten enslaved men and women in LaGrange were slated to be the next victims of the “stampede” to southern slave markets. According to one account, they were “sold to go down the river” the same day they escaped. Likely fearing they would be separated from family members at the auction block, these five men and five women instead set off on their own nighttime “stampede” across the Mississippi River on Monday, November 7. Soon after, the stolen flatboat used in the escape was found floating adrift near Quincy, Illinois, a riverside town that was home to a robust antislavery community. Whether the freedom seekers navigated to Quincy with aid from free African Americans or white antislavery activists, or on their own, remains unclear. However, LaGrange slaveholders were quick to point the finger at white antislavery activists in Quincy, rather than acknowledge the possibility that enslaved people might have been the authors of their own escape. The LaGrange American suggested that “an abolition conductor” had guided the ten bond people across the river, and even suspected that there were antislavery “agents” operating in LaGrange itself. [5]

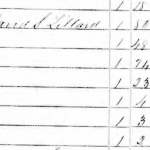

Then on Friday night, November 11, an enslaved man escaped from the LaGrange residence of slaveholder David S. Lillard, a well-to-do 49-year-old farmer. Back in 1850, Lillard had held seven enslaved people, and by the time of the 1860 Census he claimed nine people as his property. They included four young children––a nine-year-old female, and three male children aged six, four, and -one––three other males in their early teens, a 36-year-old woman, and a man around the same age, likely a family. Although Lillard did not acknowledge to census takers in 1860 that any of his bond people were “fugitives from the state” (though quite a few of his neighbors did), a 50-year-old enslaved man who appeared on the 1850 Census is absent from Lillard’s list of human property ten years later. Whether this man, who would have been around 59 at the time of the LaGrange stampede, was the freedom seeker described is unknown. While the man’s identity remains clouded in uncertainty, he became the eleventh bond person to escape from LaGrange in the span of just four days. Even if his flight was not directly connected to the “stampede” earlier that same week, LaGrange slaveholders still viewed it as part of a broader pattern of escapes that was destabilizing slavery in northeastern Missouri. [6]

In the meantime, seven other LaGrange slaveholders were working feverishly to track down the ten freedom seekers who had escaped earlier in the week. They offered a sizable $2,650 reward, all while focusing their attention on Quincy. With the aid of Sheriff James Hendrickson of Adams County, Illinois, the slaveholders searched a Quincy home belonging to “a leading black republican” on Saturday, November 12, but came up empty-handed. Even Quincy’s Democratic press, the Herald,  drolly commented that “the Sheriff was at least four days behind time.” In nearby Hunstville, Missouri, the editor of the Randolph Citizen expressed what was fast becoming the general consensus: “There seems to be a poor chance for their recovery.” [7]

drolly commented that “the Sheriff was at least four days behind time.” In nearby Hunstville, Missouri, the editor of the Randolph Citizen expressed what was fast becoming the general consensus: “There seems to be a poor chance for their recovery.” [7]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

On Thursday evening, November 17, several groups of freedom seekers arrived in Chicago. They included a party of five who had fled from near Richmond, Virginia, a group of 12 from Kentucky, and a contingent of 13 from Missouri. Although it is by no means certain, both the time frame and number of Missourians involved suggest that the LaGrange escapees may have been among them. The runaways, 30 in all, passed through Chicago that night. Whether they journeyed to Canada, as the Chicago Journal reported, is uncertain. Northern newspapers often used the term “Canada” as a catchword for freedom, even if escapees were not actually headed for Canadian soil. For instance in December 1854, Chicago papers intimated that a group of 17 freedom seekers from St. Louis had already left for Canada, though the runaways were still in the city days later. [8]

Regardless of whether the LaGrange freedom seekers made their way to Chicago, or sought refuge elsewhere, their daring escape clearly brewed consternation among Missouri slaveholders. In late November, an editor in Lewis County (where the LaGrange stampede occurred) bemoaned the “exodus of slaves [that] has taken place within the past few weeks.” Many slaveholders “have become alarmed at the losses sustained,” though most still blamed “abolitionists and negro-thieves” as the chief culprits, sidestepping enslaved people’s own aspirations for freedom and shifting focus to outside agitators, real or imagined. [9]

As white Missourians’ responses reveal, the repeat “stampedes” did more than hit the pockets of slaveholders, but unsettled the very foundations of slavery in northeastern Missouri. Local slaveholders were clearly reeling on November 28, when the county seat of Monticello played host to a meeting where “those interested in Slave property” contemplated forming “an organization to protect themselves from the depredations of negro-thieves.” The proceedings do not survive, though a Lewis County newspaper’s vow to “make an example of every negro-thief found in the State” offers a window into what the aggrieved slaveholders likely discussed. However, around the same time as the meeting at Monticello was underway, enslaved people some 20 miles to the south in the town of Emerson were “making preparations for a general stampede.” The plot was detected and quashed, but the attempted group escape only added to slaveholders’ concerns. Although slaveholding Missourians preferred to cast blame at outside forces, the mounting number of stampedes revealed more about the pressures confronting slavery from within than without. [10]

Meanwhile, the “exodus” of enslaved people being sold southward to slave markets continued at a steady clip. According to the Canton North-East Reporter (in Lewis County), and a journal in neighboring Hannibal, Missouri, slave traders were combing “through all the counties of North Missouri, buying up the slaves rapidly at high prices.” The Hannibal serial estimated that during one week in mid-November, “over 100 slaves, from Lewis, Clark and Scotland counties” had been hauled onto boats and transported south for sale. [11]

FURTHER READING

The first and most detailed report about the escape was published in the Lagrange American on November 12, and later excerpted by the Glasgow Weekly Times. On November 14, the St. Louis News drew upon the American‘s report and published a shorter version, with details not included by the Glasgow Weekly Times, that was widely circulated throughout the country. [12]

Despite garnering national attention in late 1859, the LaGrange stampede has received only brief mentions from scholars. In her book Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves (2004), Harriet Frazier quotes from the copious press reports about the escape while examining newspaper coverage of Missouri escapes during the 1850s. [13] More recently, Richard Blackett’s authoritative study The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018) cites the LaGrange escape as among the “wave of ‘stampedes'” from Missouri after 1850. [14]

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1859 (Newspapers.com)

- Cleveland OH Daily Leader, November 18, 1859 (Newspapers.com)

- “Bound Down the River,” an 1870 lithograph by Currier & Ives depicts a flatboat on the Mississippi River. (Springfield Museum)

- A July 1846 image of a flatboat in Bayou Sara, Louisiana, by artist Henry Lewis. (SteamboatTimes)

- Enslaved people are helped out of a boat at League Island, near Philadelphia. (William Still, The Underground Railroad, 1872)

- Slaveholder David Lillard held seven people in the 1850 Census. (Ancestry)

- Slaveholder David Lillard held nine enslaved people as of 1860. (Ancestry)

[1] LaGrange, MO American, November 12, 1859, quoted in “Negro Stampede,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 17, 1859; St. Louis News, November 14, 1859, quoted in “Stampede of Negroes from Missouri,” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1859.

[2] LaGrange, MO American, November 12, 1859, quoted in “Negro Stampede,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 17, 1859; St. Louis News, November 14, 1859, quoted in “Negro Stampede,” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes in Missouri,” Cleveland, OH Daily Leader, November 18, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County MO,” New Orleans Sunday Delta, November 20, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County,” Newburyport, MA Morning Herald, November 22, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County, Missouri,” Jackson, MS Semi-Weekly Mississippian, November 23, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County,” Lowell, MA Daily Citizen and News, November 23, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County,” Warren, OH Western Reserve Chronicle, November 23, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes,” Franklin, KY Tri-Weekly Kentucky Yeoman, November 29, 1859; New York Times, November 30, 1859; “Stampede of Negroes from Lewis County,” Groton, MA Railroad Mercury, December 1, 1859; Toledo, IA Transcript, December 8, 1859.

[3] Detroit Advertiser, quoted in “A Large Underground Arrival,” Douglass’ Monthly, November 1859; “Signs Not to be Mistaken,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 9, 1859; “Twenty-Six Missouri Negroes Arrived in Canada,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 17, 1859.

[4] Detroit Advertiser, quoted in “A Large Underground Arrival,” Douglass’ Monthly, November 1859; “Signs Not to be Mistaken,” St. Louis, MO Democrat, November 9, 1859; LaGrange, MO American, November 12, 1859, quoted in “Negro Stampede,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 17, 1859.

[5] “Negro Stampede,” Cleveland, OH Daily Herald, November 19, 1859; LaGrange, MO American, November 12, 1859, quoted in “Negro Stampede,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 17, 1859; St. Louis News, November 14, 1859, quoted in “Stampede of Negroes from Missouri,” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1859.

[6] St. Louis News, November 14, 1859, quoted in “Stampede of Negroes from Missouri,” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1859; 1850 U.S. Census, District 48, Lewis County, MO, Family 280, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 48, Lewis County, MO, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Union Township, Lewis County, MO, Family 728, Ancestry; 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Union Township, Lewis County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]. Although Lillard’s views on the looming secession crisis are unknown, several years after the 1859 escape one of his sons, David E. Lillard, enlisted in a Confederate unit. See Margaret Thompson Winkler, Carolina Nigg, William Johnson Frazier, The “Long Tree” and Others: Longs, Davises, Thompsons, Cratins, and Slatons (Montgomery, AL: Uchee Publications,1995), 32. Later in 1865, the Lagrange American reported that “an athletic young negro named Henry, formerly the slave of David Lillard,” was arrested for allegedly attempting to rape a young woman. It is unclear if the paper referred to David S. Lillard, or his son who had fought for the Confederacy. See LaGrange American, August 27, 1865, quoted in St. Louis, MO Tri-Weekly Missouri Democrat, August 2, 1865.

[7] Quincy, IL Daily Herald, November 14, 1859; Hannibal, MO Daily Messenger, November 15, 1859; Huntsville, MO Randolph Citizen, November 18, 1859.

[8] “Negro Stampede,” Cleveland, OH Daily Herald, November 19, 1859; “Underground Railroad Business,” Cleveland, OH Daily Leader, November 21, 1859.

[9] “Leaving,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 24, 1859; The Glasgow Weekly Times quoted an unnamed Lewis County newspaper, which it identified only as “Senator Green’s Home Organ,” (US Senator James Green of Missouri) suggesting it was either a Canton or Monticello paper.

[10] “Leaving,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 24, 1859; “The Latest News,” Hannibal, MO Daily Messenger, November 26, 1859; Hannibal, MO Daily Messenger, December 6, 1859. See post on Hannibal Messenger.

[11] Hannibal, MO Gazette, “The Slave Exodus,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 24, 1859; Canton, MO North-East Reporter, quoted in “The Slave Exodus,” Baltimore Sun, November 29, 1859. According to the Library of Congress, copies of the Canton North-East Reporter do not survive for 1859.

[12] LaGrange, MO American, November 12, 1859, quoted in “Negro Stampede,” Glasgow, MO Weekly Times, November 17, 1859; St. Louis News, November 14, 1859, quoted in “Stampede of Negroes from Missouri,” Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1859. According to the Library of Congress, the Lagrange American is held on microfilm at the State Historical Society of Missouri.

[13] Harriet Frazier, Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those who Helped Them, 1763-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004), 102. See post. Frazier cites an article about the escape from the Louisiana Journal (possibly from Louisiana, MO), which apparently was published in June 1860. But the details of the escape correspond to those of the November 1859 stampede described in this post.

[14] Richard J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 140, 234.