DATELINE: ST. LOUIS, JULY 14, 1856

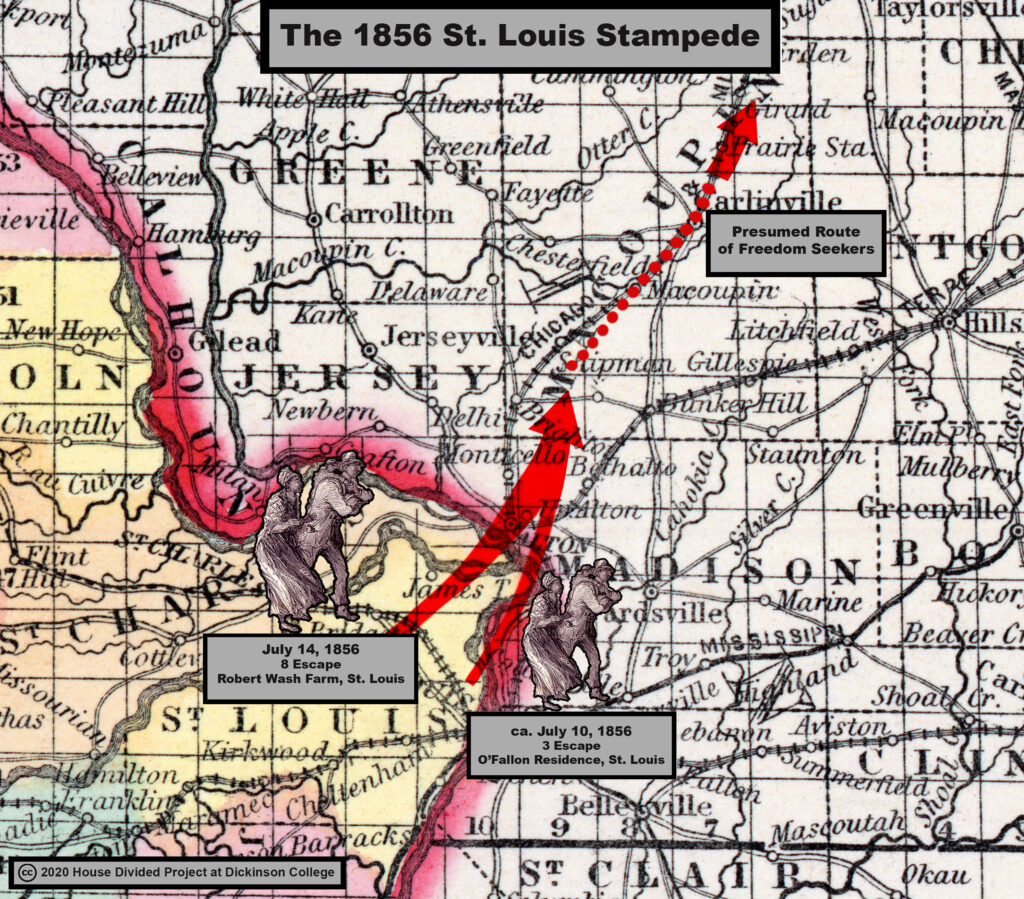

On Monday night, July 14, 1856, a group of eight to nine enslaved Missourians set out on their quest for freedom. Leaving the farm of slaveholder Robert Wash, a 65-year-old retired judge who resided on the outskirts of St. Louis, this contingent of freedom seekers charted an unknown course to liberty. Yet while the freedom seekers’ exact path is difficult to ascertain, the motivations underlying their “stampede” for freedom are somewhat easier to deduce. The group of escapees comprised a family unit––”a man and wife, three sons, two daughters, and the wife’s sister,” as reported in the St. Louis Republican. The freedom seekers may have been spurred to action by Wash’s declining health in the summer of 1856––he would die just months later, in November. Likely fearing separation at an estate sale, they chose to strike out to gain their freedom and preserve their family. [1]

These freedom seekers, whose names are unknown, may have joined with three other enslaved Missourians, held by prominent St. Louis citizen John O’Fallon. The trio had escaped from O’Fallon “a few nights previous” to July 14, and the city’s leading papers instantly suspected that the two group escapes were connected. “Several other slaves are supposed to be in their company on the underground track,” noted the editors of the Republican. Baffling St. Louis’ coterie of elite slaveholders, the freedom seekers also undoubtedly conjured memories of a pair of similar “stampedes” that had occurred less than two years before, in October and November 1854. Those large group escapes had involved enslaved men and women claimed by Robert Wash’s neighbor, Richard Berry, and his brother, Martin Wash. [2] Coming in their wake, the July 1856 stampede further unsettled slaveholders, while demonstrating the precarious nature of slavery along the Missouri-Illinois border.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

At least two initial reports from St. Louis newspapers classified the July 1856 escapes as a “stampede.” Just days after the escapes, the St. Louis Republican and Leader both ran brief reports entitled “Slave Stampede,” while the St. Louis Democrat employed a variant of the term, headlining their column “Exodus of Slaves.” Over the following weeks, at least four other newspapers throughout the country picked up the story, each utilizing the term “stampede.” The New Orleans Times-Picayune and New York-based National Anti-Slavery Standard ran the headline “Slave Stampede at St. Louis,” while the Burlington, Iowa Hawk-Eye and New Lisbon, Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle reprinted reports from the St. Louis Leader under the title “Slave Stampede.” [3]

MAIN NARRATIVE

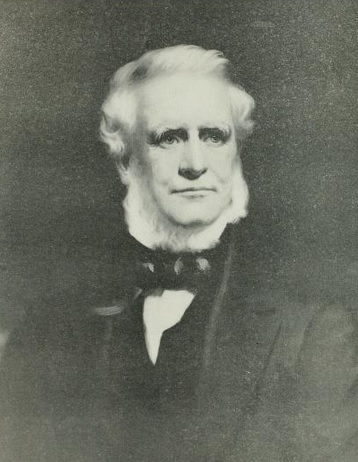

The 11-12 freedom seekers who escaped from St. Louis in July 1856 were claimed by two influential and well-to-do residents of the city. Colonel John O’Fallon, a 64-year-old veteran of the War of 1812, was also the nephew of acclaimed explorer William Clark. O’Fallon had first settled in St. Louis in 1818, where he started a trading business. However, the bulk of his wealth came as a result of his first marriage to Harriett Stokes, whose family owned a large amount of valuable real estate near St. Louis. Over the ensuing decades, O’Fallon established himself as one of the leading citizens of St. Louis, exerting a prominent presence in banking and railroading endeavors, as well as philanthropic pursuits (he was noted for his support of the nascent Washington University). O’Fallon had a residence and office in downtown St. Louis, as well as a property outside town. Yet his immense fortune and reputation was maintained and bolstered through the labor of enslaved men and women. In 1830, O’Fallon laid claim to 33 enslaved people, and by the time of the 1850 Census, he held some 42 enslaved people. [4]

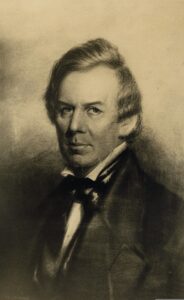

Born in Virginia in 1790, Robert Wash had settled in St. Louis in the wake of the War of 1812––around the same time as O’Fallon. After serving as U.S. District Attorney in the Monroe administration, Wash was appointed to the Missouri Supreme Court in 1825, serving until 1837. Like O’Fallon, he too was a savvy investor, and his real estate speculations won him a “large fortune,” estimated at $100,000 in the 1850 Census. As a result, Wash was able to enjoy a comfortable retirement in his “commodious home” and farm just outside of St. Louis, where in 1850 he held 32 enslaved people, ranging in age from (reportedly) 103 to a one-year-old infant. [5]

Moreover, both O’Fallon and Wash were unabashedly pro-slavery. O’Fallon headed the city’s Anti-Abolitionist Society, while Judge Wash had earned a reputation during his time on the bench for dissenting in freedom suits. O’Fallon’s identity as a slaveholder had already been brought to the attention of Northern readers some nine years prior to the 1856 stampede, when Missouri freedom seeker William Wells Brown mentioned an enslaved person sold by “Colonel John O’Fallon, who resided in the suburbs” in his widely circulated 1847 Narrative. Brown also noted that O’Fallon’s brother, Benjamin O’Fallon, kept “five or six” dogs “to hunt runaway slaves with.” [6]

Retired judge and slaveholder Robert Wash lived on the outskirts of St. Louis. (State Historical Society of Missouri)

While both men had likely read reports in St. Louis papers about the pair of stampedes that had rocked the city less than two years earlier, Robert Wash had numerous personal connections to the November 1854 stampede. His friend and neighbor, Richard Berry, had fumed as five enslaved people claimed by him fled in the stampede, while his older brother, Martin Wash, reported the escape of two enslaved people from his farm. [7] Given that the trio of slaveholders lived in close proximity to one another on the outskirts of St. Louis, it is possible that the family of enslaved Missourians who left Wash’s farm in 1856 were related to part of the group of 17 freedom seekers who escaped in November 1854.

What remains clear is that “a few nights” after the escape of three enslaved people from John O’Fallon’s residence, on Monday night, July 14, the family held by Wash left the retired judge’s farm and set off for “parts unknown.” Considering that Wash had already drafted his will several years prior, and appears to have been in declining health by the summer of 1856, the fear of separation at an estate sale may have prompted the family’s escape. The following day, a reward of $1,500 was posted for the “apprehension of eight negroes,” while multiple St. Louis papers acknowledged rumors that “several other slaves” had joined the “stampede.” Meanwhile, unwilling to recognize the agency of the enslaved to forge their own paths to freedom, the St. Louis Democrat pointed figures at “Underground railroad agents” who “are said to have assisted” the freedom seekers. [8]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

After the initial flurry of reports, St. Louis papers made no further mention of the July 1856 stampede. While the ultimate fate of the 11-12 freedom seekers is unclear, no news of their recapture appeared in the columns of Missouri papers. If the family of eight held by Robert Wash had indeed feared an estate sale was imminent, their suspicions were well-founded. Just four months after the stampede, Wash died on the day after his 66th birthday. [9]

In the meantime, John O’Fallon remained one of St. Louis’s most recognized citizens, and still held 38 enslaved people as of the 1860 Census. As the Civil War engulfed Missouri and the entire nation, O’Fallon emerged as an avowed Unionist. He even grew close to Union Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, during the general’s brief stint in St. Louis in 1861. In his memoirs, Sherman recalled O’Fallon as a “wealthy gentlemen who resided above St. Louis.” The pair, remembered Sherman, took daily walks “up and down the pavement” outside the general’s office as they “deplored the sad condition of our country, and the seeming drift toward dissolution and anarchy.” O’Fallon lived to see the end of the war––and the end of slavery in Missouri––before his death in December 1865, at the age of 74. [10]

FURTHER READING

Initial reports published in the St. Louis Democrat and Republican offer the most detailed information about the July 1856 stampede. However, various papers offered conflicting identities of the affected slaveholders, with the Democrat apparently mistaking Robert Wash for a “Major West,” while the Republican and St. Louis Leader both named “John O’Fallon jr” as the other slaveholder. Given that O’Fallon’s son, John Julius O’Fallon (sometimes referred to as “John O’Fallen, Jr.” during the 1860s) was 16 at the time of the escapes, it is strains credulity to believe he was the slaveholder involved. [11]

The July 1856 stampede has received little attention from scholars, until Richard Blackett’s The Captive’s Quest for Freedom (2018). Blackett briefly discusses the escape in the context of a rising trend of group escapes in the region during the mid-1850s. [12]

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

- St. Louis, MO Republican, July 16, 1856 (State Historical Society of Missouri)

- St. Louis, MO Democrat, July 16, 1856 (Newspapers.com)

- New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 23, 1856 (Newspapers.com)

[1] “Exodus of Slaves,” St. Louis Democrat, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Republican, July 16, 1856; Robert Wash, Will and Probate Records, June 21, 1852, Case 3752, Missouri Wills and Probate Records, 1766-1988, Ancestry.

[2] “Exodus of Slaves,” St. Louis Democrat, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Republican, July 16, 1856; Wash, Will and Probate Records, June 21, 1852, Missouri Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry.

[3] “Exodus of Slaves,” St. Louis Democrat, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Republican, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede at St. Louis,” New Orleans (LA) Times-Picayune, July 23, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” New Lisbon (OH) Anti-Slavery Bugle, August 2, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” Burlington, IA Hawk-Eye, August 6, 1856; “Slave Stampede at St. Louis,” New York National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 9, 1856.

[4] Morrison’s St. Louis Directory (St. Louis: Missouri Republican Office, 1852), 191, [WEB]; Kennedy’s Saint Louis City Directory (St. Louis: R.V. Kennedy, 1857), 167, [WEB]; Richard Edwards and M. Hopewell (eds.), Edwards’s Great West and her Commercial Metropolis (St. Louis: Edward’s Monthly, 1860), 79-82 [WEB]; Walter B. Stevens, St. Louis: The Fourth City, 1764-1909 (St. Louis: S.J. Clarke, 1909), 1076, [WEB]; Eric Sandweiss (ed.), St. Louis in the Century of Henry Shaw: A View beyond the Garden Wall (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2003), 119 [WEB]; 1830 U.S. Census, St. Louis Township, St. Louis, MO, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 82, St. Louis Wards 2 and 4, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB].

[5] 1850 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, District 82, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; J. Thomas Scharf, History of Saint Louis City and County (Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1883), 2:1471, [WEB]; Find A Grave, [WEB]; Horace W. Fuller (ed.), The Green Bag: A Useless but Entertaining Magazine for Lawyers (Boston: Boston Book Company, 1891) 3:168, [WEB].

[6] William Wells Brown, Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1847), 22, 42, [WEB]; Louis S. Gerteis, Civil War St. Louis (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 2001), 22; Kenneth Clarence Kaufman, Dred Scott’s Advocate: A biography of Roswell M. Field (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1996),144; Harriet C. Frazier, Slavery and Crime in Missouri, 1773-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2001), 55, [WEB]; Harriet C. Frazier, Runaway and Freed Missouri Slaves and Those Who Helped Them, 1763-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004), 55; Edlie L. Wong, Neither Fugitive Nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 138-140; Kelly Marie Kennington, In the Shadow of Dred Scott: St. Louis Freedom Suits and the Legal Culture in Antebellum America (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2017), 1-4.

[7] Wash, Will and Probate Records, June 21, 1852, Missouri Wills and Probate Records, Ancestry; “Another Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Democrat, November 30, 1854; “What is to Be Done Now!,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, December 10, 1854; 1850 U.S. Census, District 82, St. Louis County, MO, Family 1121, Ancestry; 1850 U.S. Census, District 82 St. Louis County, MO, Family 1246, Ancestry; Richard Berry was named the administrator of Robert Wash’s estate in a will made out in 1853, and Martin Wash was a witness.

[8] “Exodus of Slaves,” St. Louis Democrat, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Republican, July 16, 1856.

[9] Find A Grave, [WEB].

[10] 1860 U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, St. Louis Township, St. Louis County, MO, Ancestry; Find A Grave, [WEB]; William Tecumseh Sherman, Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman (New York: Library of America, 1990), 1:187, [WEB]; One of O’Fallon’s sons, John O’Fallon, Jr., delivered a “powerful and eloquent speech” at a neighboring Jefferson County, MO Union Meeting held in January 1861. See “Jefferson County Union Meeting,” St. Louis Democrat, January 29, 1861.

[11] “Exodus of Slaves,” St. Louis Democrat, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Republican, July 16, 1856; “Slave Stampede,” St. Louis Leader, quoted in New Lisbon, OH Anti-Slavery Bugle, August 2, 1856.

[12] Richard Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 139.