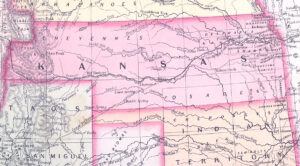

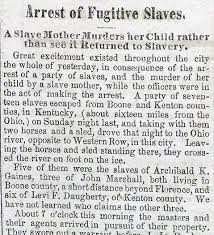

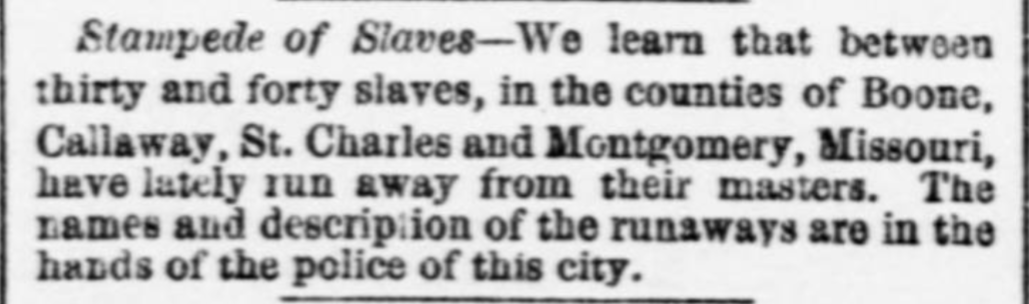

St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, February 22, 1862 (Courtesy of the State Historical Society of Missouri)

Search Summary

- Search conducted by Amanda Donoghue and Cooper Wingert from April 8 to May 1, 2019

- Keywords: slave stampede, stampede of slaves, negro stampede, negro exodus

- Total: 27 (including five episodes from Missouri)

Top Results

- “We noticed last week that a sort of stampede had taken place among the blacks, in the neighborhood of Dover, and that it was suspected that white men were concerned in inducing slaves, in that locality to leave their masters.” (“Runaways,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 28, 1854)

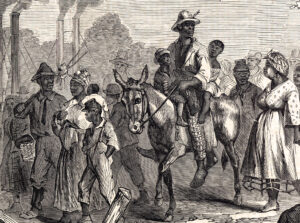

- In October 1856, the editors of the Missouri Republican reprinted a column entitled “Another Stampede” originally published by the Palmyra Whig. The piece complained that “a sort of regular recruiting duty imposed on the local press of this portion of Missouri, of late, is the chronicling of frequent departures of slaves for parts unknown.” The most recent “stampede” involved a free African-American named Isaac McDaniel, who “stole not only his wife, but some four or five other slaves in the neighborhood” of Hannibal, Missouri. McDaniel’s party also “stole a horse and buggy belonging to his wife’s master,” to effect their escape. (“Another Stampede,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, October 28, 1856, quoting the Palmyra, MO Whig.)

- “We learn that between thirty and forty slaves, in the counties of Boone, Callaway, St. Charles and Montgomery, Missouri, have lately run away from their masters. The names and descriptions of the runaways are in the hands of the police in this city.” (“Stampede of Slaves,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, February 22, 1862)

- “We saw five runaway slaves taken to the calaboose yesterday evening by persons who had taken them…The secessionists have charged that the purpose of this war was to free the negroes, and have talked so much about it, that it is no wonder their negroes leave them. They may blame themselves for the present stampede among slaves.” (“Runaway,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, September 19, 1861)

- “But the successful arrest and extradition of no less than five fugitives on the third, opened their eyes to new danger…At one time they believed the Marshal had in his hands fifteen additional warrants for fugitives; at another, the story was that there were six hundred Missourians in the city looking for their lost negroes. Indeed, such has been the terror among fugitives during the last three or four days, that in every strange face they beheld a slave owner and in every lamp-post an officer. The stampede for Canada became general, with all who could get away.” (St. Louis Missouri Republican, April 9, 1861)

Select Images

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, June 19, 1854 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, September 28, 1854 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, September 7, 1859 (Courtesy of the Historical Society of Missouri)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, October 24, 1859 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, October 31, 1859 (Courtesy of the Historical Society of Missouri)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, April 9, 1861 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, April 9, 1861 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, September 19, 1861 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

- St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, September 24, 1863 (Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society)

General Notes

- The St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican began publishing in St. Louis Missouri in the 1830s, but it is available digitally from 1854 to 1873. It is accessible online through the State Historical Society of Missouri’s digital newspaper collection.

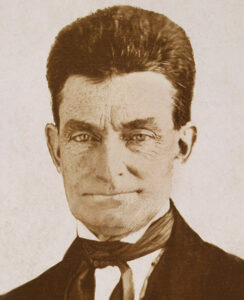

- In addition the the article shown above about “Old Brown of Ossawatomie,” the paper published a number of other articles about John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry.

- “Thatcher’s letter” is the publication of a letter written by Lawrence Thatcher of Memphis to John Brown, but it was intercepted by the government on the way to Harper’s Ferry.

- Not all papers digitized on the website are accurately searchable, so other articles about stampedes published by this paper may exist.