Contributing Editors for this page include Mary Beth Donnelly, Michelle Grasso, Marsha Greco and Adam Sonstroem

Ranking

#35 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

Audio Version

On This Date

[Editorial Note: this undated fragment has traditionally been attributed to September 1862]

HD Daily Report, September 2, 1862

The Lincoln Log, September, 1862

Close Readings

Mary Beth Donnelly, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), September 2, 2013

Michelle Grasso, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), October 1, 2013

Marsha Greco, “Understanding Lincoln” blog post (via Quora), October 1, 2013

Lincoln Meditation Close Reading from Adam Sonstroem on Vimeo.

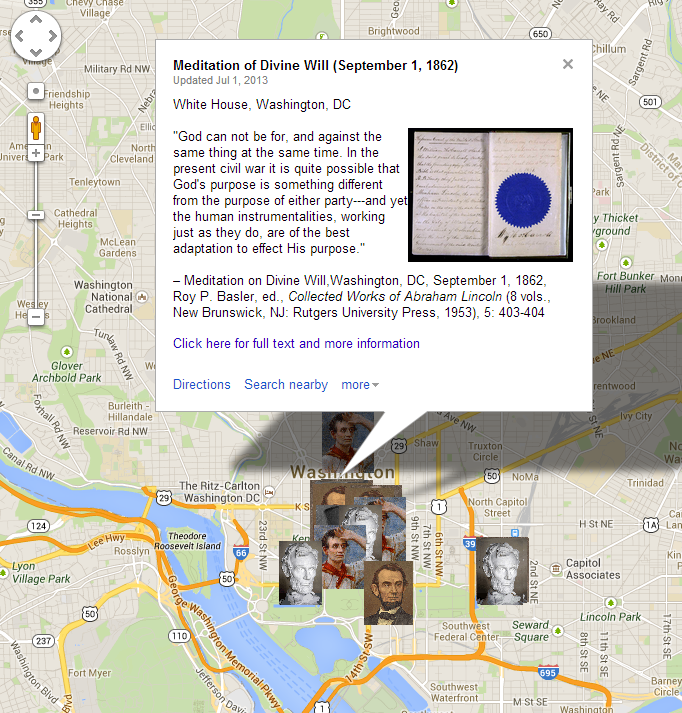

Custom Map

How Historians Interpret

“In a private memo for himself, probably written in the summer of 1864, Lincoln ruminated on the Lord’s intentions. Dismayed by the terrible bloodshed of the spring campaigns, he asked why a benevolent deity would allow it: ‘The will of God prevails. In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God can not be for, and against the same thing at the same time. In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party – and yet the human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect His purpose. I am almost ready to say this is probably true – that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet. By his mere quiet power, on the minds of the now contestants, He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds.’ Lincoln had long been pondering the will of God, which was not clear to him.”

–Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2 volumes, originally published by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008) Unedited Manuscript by Chapter, Lincoln Studies Center, Volume 2, Chapter 34 (PDF), 3798-3799.

“An officer confessed that ‘our men are sick of war. They fight without an aim and without enthusiasm.’ Lincoln fell into depression. Edward Bates described him as ‘wrung by the bitterest anguish – said he felt almost ready to hang himself.’ Gideon Welles said the president was ‘sadly perplexed and distressed by events.’ If so, it’s no wonder he thought more than ever about divine providence. In a fragment on divine will he wondered which side God truly favored, because ‘God can not be for, and against the same thing at the same time. He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest,’ thought Lincoln, ‘yet the contest began. And having begun he could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceed.’”

–Louis P. Masur, Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War for the Union (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 93.

“In September 1862, Lincoln penned his ‘Meditation on the Divine Will,’ which clearly foreshadows the later speech.He leaves no doubt whatever as to God’s complete sovereignty: ‘The will of God prevails.’ The war exists, leading to Lincoln’s humble supposition concerning God’s will: ‘I am almost ready to say this is probably true—that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet.’ Moreover, the God whose will Lincoln contemplates is a personal God, actively involved in human affairs: ‘By his mere quiet power, on the minds of the now contestants, He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. . . . And . . . He could give the final victory to either side any day.’ We agree with Michael Nelson that ‘clearer evidence would be hard to find demonstrating not only that Lincoln’s religious views had changed over the years but also how they had changed. In his 1846 election handbill Lincoln had written that the human mind is governed by ‘some power, over which the mind itself has no control.’ Sometime between then and 1862, he had identified to his own satisfaction its source—no longer ‘some power,’ but rather ‘his mere quiet power.’’ Lincoln no longer believes in a mere abstract force, but in divine agency, a being with an independent will and the power to implement it. Beyond the content of the Meditation, it is important to emphasize that the document was not intended for publication but rather reflected Lincoln’s private thoughts. John Nicolay and John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretaries, state that Lincoln wrote it ‘absolutely detached from any earthly considerations . . . It was not written to be seen of men. It was penned in the awful sincerity of a perfectly honest soul trying to bring itself into closer communion with its Maker.’ Consequently, as Ronald White notes, the Meditation ‘becomes a primary resource in answering the question of the integrity of Lincoln’s ideas in the Second Inaugural.’ As ‘an authentic expression of his innermost views,’ this document in itself undermines the please-the-public dismissal of the Second Inaugural.”

–Samuel W. Calhoun and Lucas E. Morel, “Abraham Lincoln’s Religion: The Case for his Ultimate Belief in a Personal, Sovereign God,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 33, no. 1 (2012): 38-74.

NOTE TO READERS

This page is under construction and will be developed further by students in the new “Understanding Lincoln” online course sponsored by the House Divided Project at Dickinson College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. To find out more about the course and to see some of our videotaped class sessions, including virtual field trips to Ford’s Theatre and Gettysburg, please visit our Livestream page at http://new.livestream.com/gilderlehrman/lincoln

Searchable Text

The will of God prevails. In great contests each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God can not be for, and against the same thing at the same time. In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party—and yet the human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect His purpose. I am almost ready to say this is probably true—that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet. By his mere quiet power, on the minds of the now contestants, He could have either saved or destroyed the Union without a human contest. Yet the contest began. And having begun He could give the final victory to either side any day. Yet the contest proceeds.