Ranking

#14 on the list of 150 Most Teachable Lincoln Documents

Annotated Transcript

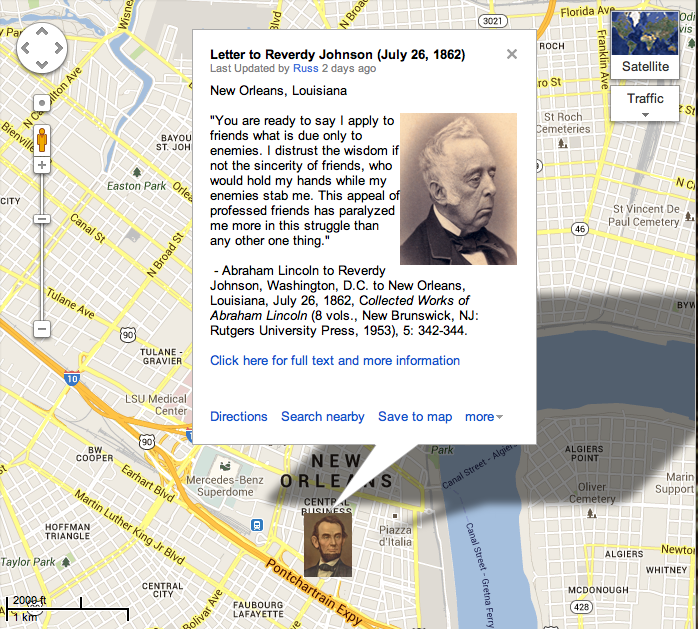

Context. In this striking note to a Unionist senator from Maryland, Lincoln coolly informed Reverdy Johnson that he would play “any available card” in order to defeat the rebellion. Johnson had traveled to Union-occupied Louisiana and had reported to the president that southern unionists in the state were upset over Union general John W. Phelps’s enticement policies regarding fugitive slaves. Phelps was an abolitionist. Lincoln responded by questioning the “sincerity” of these so-called friends of the government. He was sensitive on this point of Union policy regarding slavery because just a few days earlier, he had announced privately to his cabinet that he planned to emancipate all slaves in Rebel territory after January 1, 1863. (By Matthew Pinsker)

Audio Version

On This Date

HD Daily Report, July 26, 1862

The Lincoln Log, July 26, 1862

Image Gallery

- Lincoln in 1862

- Reverdy Johnson

- John Wolcott Phelps

- Rioting in Baltimore, 1861

Close Readings

Custom Map

Other Primary Sources

Reverdy Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, July 16, 1862

Reverdy Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, September 5, 1862

Abraham Lincoln to George Shepley, November 21, 1862

The Daily Picayune, “Notice of Election,” December 2, 1862

George Shepley to Abraham Lincoln, December 9, 1862

How Historians Interpret

“The failure of the Peninsular campaign marked a key turning point in the war. If McClellan had won, his triumph – combined with other successes of Union arms that spring, including the capture of New Orleans, Memphis, and Nashville – might well have ended the war with slavery virtually untouched. But in the wake of such a major Union defeat, Lincoln decided that the peculiar institution must no longer be treated gently. It was time, the thought, to deal with it head-on. As he told the artist Francis B. Carpenter in 1864, ‘ It had got to be midsummer, 1862. Things had gone from bad to worse, until I felt that we had reached the end of our rope on the plan of operations we had been pursuing; that we had about played our last card, and must change our tactics, or lose the game! I now determined upon the adoption of the emancipation policy.’ On July 26, the president used similar language in warning Reverdy Johnson that his forbearance was legendary but finite. To New York attorney Edwards Pierrepont, Lincoln similarly explained: ‘It is my last trump card, Judge. If that don’t do, we must give up.’ By playing it he said he hoped to ‘win the trick.’ To pave the way for an emancipation proclamation, Lincoln during the first half of 1862 carefully prepared the public mind with both words and deeds.”

“If Lincoln’s endorsement of [John W.] Phelps indicated the direction the government was taking, an even clearer indication was Lincoln’s response to the Maryland unionist Reverdy Johnson. Back in June, acting on diplomatic complaints about Butler’s treatment of foreign consuls in New Orleans, the State Department had dispatched Johnson to Louisiana to investigate the matter. Overstepping his mission, Johnson reported back to Lincoln on July 16 that Louisiana unionists were becoming alienated by the drift toward emancipation, especially by the policies of General Phelps – which Lincoln had already effectively endorsed. Loyal Louisianans were beginning to worry that it was the ‘purpose of the Govt to force the Emancipation of the slaves.’ Johnson warned Lincoln that if Phelps was allowed to proceed unchecked, ‘this State cannot be, for years, if ever, re-instated in the Union.’ Lincoln’s answer to Johnson was uncharacteristically blunt. He dismissed Johnson’s claim that unionist sentiment in Louisiana was being ‘crushed out’ by Phelp’s policy. All they had to do to stop Phelps was stop the rebellion, he noted … Then he made it unmistakably clear that the time for a more concerted assault on slavery had come. ‘I am a patient man,’ Lincoln told Johnson, ‘but it may as well be understood, once for all, that I shall not surrender this game leaving any available card unplayed.'”

— James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery In The United States, 1861-1865, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2013), 249-250

“When Reverdy Johnson complained about the abrasive announcements coming from General John W. Phelps, Benjamin Butler’s abolitionist lieutenant who was now overseeing the military occupation of New Orleans, Lincoln snapped back that any Louisianans who were ‘annoyed by the presence of General Phelps’ had only to recall that Phelps was there because of them. And if they thought Phelps was bad, they should consider what Lincoln might do next. ‘If they can conceive of anything worse than General Phelps, within my power, would they not better be looking out for it?’ Wisdom should tell them that ‘the way to avert all this is simply to take their place in the Union upon the old terms.’ If they refused, they shouldn’t be surprised if they ‘receive harder blows than lighter ones.'”

Further Reading

- Matthew Pinsker, “Lincoln’s Summer of Emancipation,” in Harold Holzer and Sarah Vaughn Gabbard, eds., Lincoln and Freedom: Slavery, Emancipation and the Thirteenth Amendment (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007), 79-99.

Searchable Text