I’ve kept a folder on my computer for years entitled “family archives” where I’ve collected scanned news articles, obituaries, photos and census data. It’s the modern version of an old binder my father keeps of yellowed newspaper articles and handwritten notes. Back in April 2012 I think I spent a whole two days on the computer after the 1940 census data came out searching, locating, and saving every document with a family member’s name. What I haven’t done enough of is put these documents together or asked myself what kind of story they really tell. Inspired by the stories of Civil War soldiers and their families, I’ve mined several resources (family stories, the “family archives” file, local history archives through the Pittsfield Library, etc.) to tell you this personal story.

James Goggin’s (or Goggins) parents came to the United States from Macroom, County Cork, Ireland in the early 1830s. Eventually his family settled in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. It was there that he was born, raised, and eventually married Ellen Denny, probably sometime in his early 20s.

In April 1861 the Civil War began with the firing on Fort Sumter. That same month the Allen Guard organized volunteers from the hill towns of Western Massachusetts and marched to Springfield, MA to report for service.[1] James Goggins, age 24, was among them.

In April 1861 the Civil War began with the firing on Fort Sumter. That same month the Allen Guard organized volunteers from the hill towns of Western Massachusetts and marched to Springfield, MA to report for service.[1] James Goggins, age 24, was among them.

James Goggins would go on to serve two 90 day tours in the Union Army. He must have come to some injury during his first tour, since he terminated his service nearly two weeks before expiration. The cause, “disability”. What the disability was, I do not know. However, it must not have been serious since he apparently did return to the war again for a second tour of duty.

Gravestone of James “Civil War Jim” Goggins in St. Joseph Cemetary, Pittsfield, MA (Courtesy of Massachusetts Gravestone Photo Project)

James Goggins never saw battle. He never made it south of Maryland. The Allen Guard and 8th Massachusetts Regiment’s purpose in Baltimore was to protect railroad and communication lines. As a slave state, Maryland’s loyalty to the Union was questionable, particularly in those early days. Later, the 8th Regiment was sent to Annapolis and James Goggins, along with the other members of Company K, guarded the USS Constitution from “rebel mischief” [3] Family legend is that toward the end of his service he reportedly returned to Massachusetts via “Old Ironsides” when it returned to New England.

James Goggins survived the Civil War. He survived his brief “disability”. He survived the dangers of Maryland, Baltimore and Annapolis. But he did not survive to see the 1870s. He died in 1865 of lock jaw, or tetanus, in Pittsfield,MA. According to the 1870 US Census, he left behind not only his widow, Ellen Denny, but also two children: Ellen or “Nellie” (6) and James T. (4), likely born after his father’s death.

1870 US Census, Pittsfield, MA

Nellie, who never married, would live to the age of 96. She was buried with her parents in 1960 (see gravestone above) James T. married and had four children of his own. Both siblings remained in Pittsfield. They must have remained close. After their mother died in 1910, Nellie lived with her brother’s family for many years (according to the 1920 and 1940 Census Records, see below).

1920 United States Census; showing members of James T. Goggins’ household

1940 United States Census data

“Civil War Jim” was my great-great-great grandfather. Most of what I knew about him before today came from stories my father told me. I knew where he was born, that he had served in the Allen Guard, rode on the Constitution, and died of lock jaw. I knew he had a son James. I wouldn’t be here if he didn’t. But before today I never knew he had a daughter, or what his wife’s name was. When I came across this image of his gravestone I was very excited, but almost immediately questioned it. My own grandparents are buried in St. Joseph Cemetery, but I’ve never seen this particular one. I knew what “Civil War Jim” died of, but I’d always imagined that he’s lived longer than 27 years.

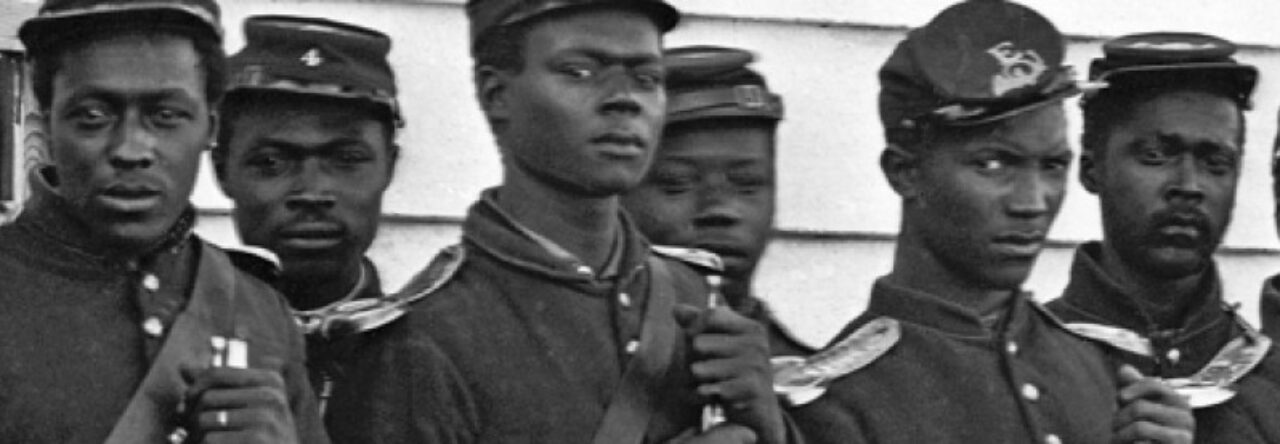

The image I had of “Civil War Jim” in my mind was always based on a cross between what I thought a perfect Civil War soldier should be and a younger version of my grandfather (another James Goggins).

Now I feel I can put together a more intimate and realistic picture of who James Goggins was. He was 23 when he went away to war – my younger brother’s age. He left at home his young wife but no children. He must have been eager to fight since he joined immediately. Service in Maryland may have been very boring, guarding railroads and ships. I’m sure Ellen was relieved that he was away from the fighting. Was his ride on the Constitution the only time he’d been “at sea”? He barely ever knew his children. He might not have even known he would have a son when he died. Ellen was lucky enough to see her husband come home from the war but at age 24 (the age I am now) she was a widow with two young children. How different was her pain and loneliness compared to women like Anne Colwell?

[1] George Warren Nason, History and Complete Roster of the Massachusetts Regiments; Minute Men of ’61 [Boston, 1910]

[2] Record of the Massachusetts Volunteers 1861-1865. Volume 1. [Adjunct General, Boston: 1868]

[3] Christopher Marcisz, “When the Civil War Began in the Berkshires”. April 11, 2011. Times Union. [http://blog.timesunion.com/berkshires/when-the-civil-war-began-for-the-berkshires/1247/]