This post is part of a new summer 2017 “DIY” (do-it-yourself) series by House Divided Project interns Rachel Morgan and Sam Weisman on how to make various types of primary source facsimiles; see posts on CDVs, stereocards, colorized photos, and letters.

A Piece of History

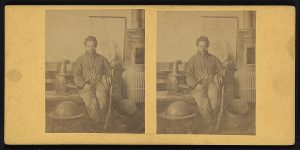

In February of 1862, the middle of the Civil War, a black janitor posed with his cleaning tools, waiting to have his photo taken. In a time when many African Americans were fighting to acquire their basic right to freedom, this janitor sat calmly in front of the camera. In comparison to the surrounding chaos of a country collapsing in on itself, this man was composed and relaxed. This photo helps to teach us a narrative of the Civil War we sometimes forget: that of everyday life in the Civil War, especially the everyday lives of employed African Americans.

In February of 1862, the middle of the Civil War, a black janitor posed with his cleaning tools, waiting to have his photo taken. In a time when many African Americans were fighting to acquire their basic right to freedom, this janitor sat calmly in front of the camera. In comparison to the surrounding chaos of a country collapsing in on itself, this man was composed and relaxed. This photo helps to teach us a narrative of the Civil War we sometimes forget: that of everyday life in the Civil War, especially the everyday lives of employed African Americans.

The Photographer’s Objective

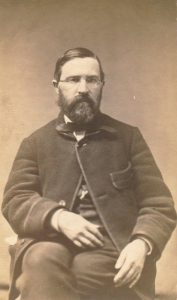

The man who took this photo, Charles Francis Himes, was a Dickinson College professor and well-regarded scholar. He pursued knowledge in a variety of fields, including mathematics, foreign languages, and the natural sciences. He also had a passion for the relatively new field of photography. Although Himes was an amateur photographer, he worked diligently at learning the craft. He experimented with different chemical recipes and mediums for developing and printing photos.[1] He was trying to find a way to preserve photographs for as long as possible. As an educator, Himes also understood the importance of pursuing and passing on this knowledge. He sometimes photographed texts for his students rather than use a printing press. He also photographed some historic documents and letters that he thought were at risk of being damaged over time.[2] Himes was dedicated to preserving photographs and the lessons they had to teach.

The Stereo Card

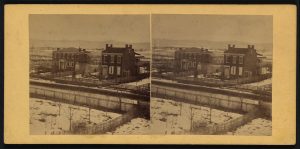

One medium of photography that Himes utilized was the stereo card. Stereo cards consist of two identical images mounted next to each other on a piece of cardstock, usually measuring 3.5 by 7 inches. The stereo card of Henry the janitor pictured to the left is an excellent example (left). When viewed through a stereoscope, these cards produce a three-dimensional image.[3] In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stereoscopes were common household items. Because they were mass-produced and easily obtainable, stereo cards made useful teaching tools. Himes used stereo cards to share photos of Dickinson College and Carlisle that he had taken. Many of his stereo cards are available for viewing through the Library of Congress.[4]

One medium of photography that Himes utilized was the stereo card. Stereo cards consist of two identical images mounted next to each other on a piece of cardstock, usually measuring 3.5 by 7 inches. The stereo card of Henry the janitor pictured to the left is an excellent example (left). When viewed through a stereoscope, these cards produce a three-dimensional image.[3] In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, stereoscopes were common household items. Because they were mass-produced and easily obtainable, stereo cards made useful teaching tools. Himes used stereo cards to share photos of Dickinson College and Carlisle that he had taken. Many of his stereo cards are available for viewing through the Library of Congress.[4]

Stereo viewer

Instructions: How to Make a Stereo Card Facsimile

Teachers today can utilize stereo cards as a teaching tool. Acquiring a replica stereoscope is simple: they are available on EBay for as little as $10.00.

- Purchase actual stereo cards to mount your facsimiles on. They can be purchased from EBay for as little as $1.75 each.

- Find a stereo card image you want to recreate in your facsimile. High-quality tiff images of stereo cards can be downloaded from the Library of Congress’ website.

- Make sure the image you downloaded is properly sized: 3.5 by 7 inches. This can be done with the formatting tool on Microsoft Word.

- Once the images are properly sized and printed, they can be mounted onto the stereo cards you purchased.

- If you do not have access to actual stereo cards, you can instead mount the images on a thick piece of cardstock or a thin piece of cardboard. Be sure to use a material that is the right thickness: a proper stereo card is about as thick as the cardboard used to make tissue boxes.

If you want to try and make a facsimile of one of Himes’ stereo cards, here are three PDF images, already properly sized for you to use. All images are courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Conclusion

Stereo card facsimiles were popular in the nineteenth century. Between 1854 and 1856 alone, the London Stereoscopic Company sold half a million cards.[5]. Because they were so easily accessible, stereo cards became important mediums in the fields of entertainment, education, and even news reporting.[6] Just as Himes and other photographers used stereo cards to spread information on those topics most important to him over a century ago, so can educators today.

Sources

- Christine L. Line, “Catching a Glimpse of Forever,” Dickinson Chronicles [Web]

- Line, “Catching a Glimpse” [Web]

- “Stereocard Collection,” University of Washington Libraries [Web]

- “Prints and Photographs Online Catalog,” Library of Congress [Web]

- Lisa Spiro, “A Brief History of Stereographs and Stereoscopes,” Rice University, 2017 [Web]

- “Stereographs,” American Antiquarian Society, 2017 [Web]

Related Articles

No user responded in this post

Leave A Reply

Please Note: Comment moderation maybe active so there is no need to resubmit your comments