February 1 is National Freedom Day in the United States and has been since 1948. The question is why? The story begins with a bit of presidential trivia but then turns into a fascinating tale of an extraordinary citizen. It was on February 1, 1865 that President Abraham Lincoln signed a joint congressional resolution proposing a Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. But any good civics student knows that the process for amending the Constitution was by no means complete. Congress (and not the president) sends amendments to the states for ratification, and it is the states that must finalize any proposed changes. The requisite number of states did not ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until December 6, 1865, an event which set off an explosion of celebrations in the North, immortalized by John Greenleaf Whittier’s once-famous poem, “Laus Deo!”:

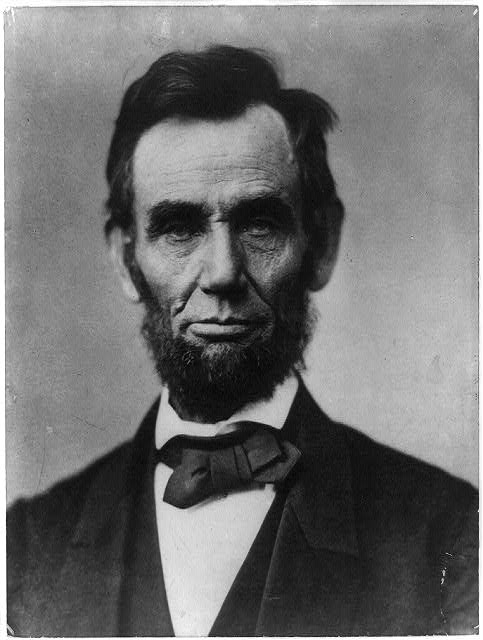

February 1 is National Freedom Day in the United States and has been since 1948. The question is why? The story begins with a bit of presidential trivia but then turns into a fascinating tale of an extraordinary citizen. It was on February 1, 1865 that President Abraham Lincoln signed a joint congressional resolution proposing a Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would abolish slavery. But any good civics student knows that the process for amending the Constitution was by no means complete. Congress (and not the president) sends amendments to the states for ratification, and it is the states that must finalize any proposed changes. The requisite number of states did not ratify the Thirteenth Amendment until December 6, 1865, an event which set off an explosion of celebrations in the North, immortalized by John Greenleaf Whittier’s once-famous poem, “Laus Deo!”:

IT is done!

Clang of bell and roar of gun

Send the tidings up and down.

How the belfries rock and reel!

How the great guns, peal on peal,

Fling the joy from town to town!

Yet Lincoln himself had appeared to acknowledge the special nature of February 1 when he placed an otherwise superfluous signature on the joint resolution. He had called the proposed amendment “a king’s cure” to the challenge of ending slavery and clearly wanted to bear witness to the transformation that was being wrought by the bloody Civil War. Though he did not live to see ratification, Lincoln’s contributions as military emancipator and advocate for constitutional abolition deserve commemoration.

That was the idea that eventually inspired a former slave to lobby Congress to designate February 1st as National Freedom Day. Richard R. Wright was a 9-year-old enslaved boy living in Georgia when Lincoln signed the joint resolution. After the war, while attending a freedmen’s school during Reconstruction, he became known as the source for yet another once celebrated poem by Whittier, this one entitled, “Howard at Atlanta,” about the visit of Union general Oliver O. Howard to a black school:

The man of many battles,

With tears his eyelids pressing,

Stretched over those dusky foreheads

His one-armed blessing.

And he said: “Who hears can never

Fear for or doubt you;

What shall I tell the children

Up North about you?”

Then ran round a whisper, a murmur,

Some answer devising:

And a little boy stood up: “General,

Tell ’em we’re rising!”

The phrase, “Tell ’em we’re rising!” became an anthem for the post-war black middle class of which young Richard Wright soon became one of the most notable embodiments. He served as an officer in the Spanish-American War and later became a renowned educator (and mentor to W.E.B. DuBois) and eventually a banker in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, a self-made man who never seemed to stop striving. At age 67, Wright enrolled in Wharton Business School to help retrain for his new commercial endeavor, The Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company. In early 1942, at age 86, he began an intensive lobbying effort for the creation of National Freedom Day. The first grassroots celebration drew 3,500 people to the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. The crowd held a mass Pledge of Allegiance in front of the Liberty Bell and then organized a patriotic parade “with forty flag-bedecked automobiles,” according to a report from the Baltimore Afro-American (Feb. 7, 1942). The turnout was especially impressive because the national climate did not seem promising for such an earnest effort. World War II had already begun, Japanese internment was about to be launched and a climate of segregation and oppression still prevailed across the South and much of the North. Attendees at this first gathering, for example, felt compelled to formally denounce a recent lynching in Missouri. Yet Wright persisted, undertaking a national speaking tour and working behind-the-scenes with various members of the Pennsylvania congressional delegation.

Seven years later, the effort finally bore fruit on June 30, 1948 when President Truman signed Public Law 842, establishing “National Freedom Day” into the federal code. The final legislation encouraged national observance of February 1st as a way to commemorate the abolition of slavery, but did not mandate a new federal holiday. That had been the original intent of Wright’s proposal, but some in Congress had objected to canceling a work day in the short and already commemoration-crowded month of February. Unfortunately, Wright was not present to fight for more. He had died in July 1947 and never lived to see the formal establishment of his dream, not so unlike Abraham Lincoln who also had been unable to witness the ratification of his.

General Sources: Hanes Walton, Jr., et.al., “R. R. Wright, Congress, President Truman and the First National Public African-American Holiday: National Freedom Day,” PS: Political Science and Politics 24 (Dec. 1991): 685-688 and Michael Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery and the Thirteenth Amendment (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

A version of this blog post also appears at Constitution Daily, a blog of the National Constitution Center.

Related Articles

No user responded in this post

Leave A Reply

Please Note: Comment moderation maybe active so there is no need to resubmit your comments