To Be Cautious or To Be Bold: The Competing Strategies of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass during the Civil War

“The friends of freedom, the Union, and the Constitution, have been most basely betrayed, deceived, and swindled.”[1] -Frederick Douglass, 1862

Introduction:

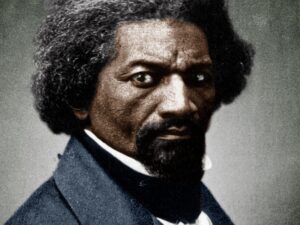

Frederick Douglass did not mince words when expressing his frustration with Abraham Lincoln’s approach to abolition and the Civil War. These were two of the most well-known 19th century figures who worked towards securing freedom for all. But, they took vastly different approaches to promote their agendas at the outbreak of the war. In contemporary politics too, contending strategies arise and factions emerge within larger coalitions. Sometimes the differences in approaches taken by people on the same side of an issue are so great that it seems like they are working against each other. Lincoln and Douglass’s debates should serve as a case example for how we should be aware that those with different strategies may be working towards the same end. Lincoln was a calculated politician who exercised caution in order to keep slavery’s opponents united, and Douglass was a radical who thought that bold speech and actions would attract supporters, but both wanted to put an end to slavery.

Interpretations of the Constitution:

Both Lincoln and Douglass interpreted the Constitution as an anti-slavery document, but Lincoln saw it as laying out the boundaries for abolition whereas Douglass saw it as an open call to action. As President of the United States, Lincoln believed it was his utmost duty to uphold and enforce the Constitution. He believed that the founders wrote the document “knowing slavery was evil but certain it was dying,” and that they compromised with slavery in order to create the Union.[2] He believed that the founders “hid slavery away, in the constitution, just as an afflicted man hides away a wen or a cancer, which he dares not cut out at once, lest he bleed to death; with the promise, nevertheless, that the cutting may begin at the end of a given time.”[3] Essentially, Lincoln thought that the Constitution allowed him to fight against slavery but also believed that the power it gave him was limited. Oakes explained that “no matter how much he personally hated slavery, the Constitution recognized it in the states where it had already existed,” so he was only able to stop the expansion of slavery, but could not interfere where it was already constitutionally recognized.[4]

On the other hand, Douglass saw the Constitution as a document that granted everyone the right to fight against slavery using whatever means were deemed necessary. Oakes explained that Douglass believed that the Constitution and its Preamble promised universal freedom and that it was significant that there was no explicit mention of slavery in the document. He thought the Constitution was “a weapon to ‘be wielded in behalf of emancipation,’” and that it “virtually commanded politicians to take aggressive action against slavery wherever it existed.”[5] In relation to the nation’s founding, he believed “if in its origin, slavery had any relation to the government, it was only as the scaffolding to the magnificent structure, to be removed as soon as the building was completed.”[6] He disagreed with Republicans, like Lincoln, who claimed that there were constitutional barriers to abolition, and he was frustrated by the fact that a document he thought called for change was inhibiting it.

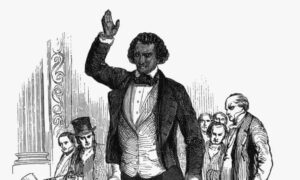

Douglass’s 1852 “Fifth of July” Speech:

Douglass took a radical approach to anti-slavery advocacy, both in his speech and actions because he believed that in order to spark change, he had to be bold. His “Fifth of July” speech in 1852 exemplified this important component of his strategy. Douglass strategically gave this speech the day after the nation’s celebration of its independence in order to make a statement about how a portion of the population, American slaves, had nothing to celebrate on the 4th of July. He explained that “this Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn,” and followed by asking “do you mean, citizens, to mock me, by asking me to speak to-day?”[7] Douglass tried to make his listeners uncomfortable in order to both capture people’s attention and move them to action.

Douglass used inflammatory language as a way to move audiences and attract followers. He referred to the institution of slavery as “the great sin and shame of America!” and said that he intended to “use the severest language I can command; and yet not one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgment is not blinded by prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right and just.”[8] It is clear that Douglass refused to censor himself in any way on the issue of slavery, publicly or privately. His use of explosive rhetoric served as a way for him to outwardly expose the hypocrisy of the nation. He stated, “at a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had I the ability, and could I reach the nation’s ear, I would, to-day, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder.”[9] Essentially, he emphasized that not only did the hypocrisy need to be exposed, it should be blasted. Douglass’s language was divisive and confrontational and served to attract followers by evoking a visceral response.

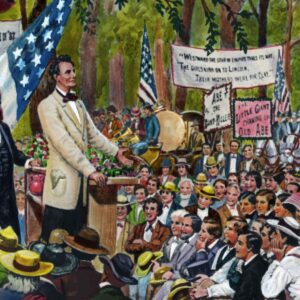

Lincoln’s 1858 “House Divided” Speech:

In Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech in 1858, he employed a relatively radical tone as he was trying to unite the opponents of slavery in the North. He gave this speech when he accepted the Republican nomination to run for Senator in Illinois, after Illinois Republicans “broke new political ground by nominating Lincoln in advance of the legislative elections as their ‘first and only choice’ for U.S. senate.”[10] In Lincoln’s speech, he argued that “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” which essentially meant that in order for the nation to maintain itself, it had to become entirely anti-slavery or pro-slavery.[11] He thus hinted that an end to slavery was inevitable and threatened that if the Union did not come together, it would not survive. He took a more explicit position against slavery, stating that “to meet and overthrow the power of that dynasty, is the work now before all those who would prevent that consummation.”[12] The “dynasty” that he referred to was slavery.

This speech was seen as radical because he outwardly took a position against slavery and because he claimed he foresaw an end to it. This was alarming to society because nobody had lived in a world in which slavery did not exist. If slavery were abolished, slaves would become free citizens and many people then feared what an integrated society would look like. Northern Democrats interpreted Lincoln’s speech as threatening because they did not want to live in a society in which white and black people were equal. While Lincoln was actually only advocating for abolition and not equality, his opponents did not see it that way.

Lincoln’s 1861 First Inaugural Address:

In reading Lincoln’s First Inaugural address, it is evident that as the possibility of war grew, Lincoln exercised more caution. Unlike his “House Divided” speech, his First Inaugural on March 4, 1861 highlighted some of the distinct elements of his anti-slavery strategy like focusing on preserving the Union while not explicitly taking a position on slavery. In describing his central message, Oakes explained, “he had no intention of interfering with slavery but every intention of enforcing the law.”[13] Lincoln stated that the “only substantial dispute,” was that “one section of our country believes slavery is right, and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong, and ought to be restricted.”[14] Lincoln suggested, as he had many times before, that his priority was to uphold the Constitution and that he would not violate its promises. Because of this, he argued that the South’s threat to secede was baseless. He went further to declare that not only was secession baseless, but “unconstitutional.”[15] He explained that “no government could make provision for its own destruction; no contract could be abrogated at the whim of only one of its signatories.”[16]

Lincoln also argued that he would not attack first, but would react to a Southern attack. Specifically, he explained “in your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war.”[17] Oakes described this as being on the “strategic defensive,” which was part of Lincoln’s conservative approach.[18] Persuaded by his Secretary of State to conclude his speech in a more disarming way, Lincoln stated, “we are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies.”[19] Oakes further explained that his speech, especially the conclusion, targeted the North more than the South in an attempt to convince the North to resist southern secession. In doing so, he was “positioning the North as the defender of the Union rather than as the invader of the South.”[20] Walking a fine line while rallying northern support was essential to Lincoln’s strategy because he thought that the only way he would be able to abolish slavery was by keeping the Union together.

What is important to recognize about Lincoln’s First Inaugural address is that he strategically left out certain points that he made in previous speeches, like his “House Divided” speech in 1858. In his “House Divided” speech, Lincoln made radical appeals to end slavery that he did not in his First Inaugural address. Where he referred to the northern democrats as “enemies” in 1858, he referred to them as “friends” in 1861.[21] He spoke eloquently, employing neutral language as to appease his entire audience. This increased caution with respect to his rhetoric served to appeal to both slaveholders and abolitionists in an attempt to keep the Union together. Lincoln did not explicitly say that abolition was the reason behind the war in his inaugural address because he knew that most northerners did not have any desire to fight a war which was dedicated to abolition. He feared that if he did take a clear position against slavery, he would lose support for the war, which he believed would be detrimental to the anti-slavery cause. The radical nature of his “House Divided” speech did not get him elected in 1858, but it made him nationally recognized. Now that Lincoln was President of the United States, he chose not to risk alienating parts of the country because without strong support, he would not be able to carry out his agenda. Lincoln’s approach, which is evident in this address, was a stark contrast to Douglass’s direct and provocative approach, and Douglass questioned his intentions.

Douglass’s 1861 Editorial:

Upon hearing Lincoln’s First Inaugural address in 1861, Douglass was critical of it because it was not immediate and all encompassing. Douglass did not find sectional reconciliation to be of any importance. Additionally, as mentioned before, Douglass believed that the Constitution enabled the government to eliminate slavery wherever it existed, so he did not agree with Lincoln’s argument that there were constitutional impediments. More importantly, Douglass interpreted Lincoln’s claim that he did not intend to interfere with slavery in the states as his “moral indifference to slavery.”[22] While Lincoln believed he was standing by the nation’s principles, so he could not “overstep his constitutional authority,”[23] Douglass interpreted this as disregard because he believed that of the principles, universal freedom was the most important. Douglass believed that this war was about abolition and should be treated as such. He thought Lincoln’s approach was morally unacceptable and that he should have been calling to abolish slavery completely.

In one of Douglass’s 1861 editorials, “Cast Off The Mill-Stone,” he expressed frustration with the fact that the war was not being acknowledged as an abolition war, when everybody knew that was at stake. He stated that “the present policy of our Government is evidently to put down the slaveholding rebellion, and at the same time protect and preserve slavery.”[24] He went on to say that “for the Government to adopt the abolition policy, would involve the loss of the support of the Union men of the Border Slave States. Grant it, and what is such friendship worth?”[25] Douglass emphasized that Lincoln knew the war was about slavery, even if he did not explicitly take a position on it for fear of losing support. But, Douglass did not care about losing support. He thought that in order to spark real change regarding abolition, the government needed to be bold and call it what it was. He did not see the point in appeasing slaveholders or anybody who wanted to preserve the institution of slavery. A bold, direct approach, he believed, would attract the right kind of supporters and then, they would be able to win the war and achieve abolition.

Conclusion:

After comparing the anti-slavery strategies of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, it is clear how even those pursuing the same end often employ different means. Lincoln believed the best way to advance his agenda was by exercising cautious and deliberate calculation, while Douglass believed it best to be bold and uncompromising. This was in part due to their individual roles in society, as Lincoln was President of an entire nation and by extension responsible for its preservation, while Douglass was a radical activist whose primary mission was eradicating slavery. It is hard to know whose approach was more effective, but examining the differences highlights the complexities involved in enacting social and political change. There may not be a right approach, and perhaps multiple approaches were necessary, but this has been demonstrated in history time and time again. Lincoln and Douglass’s debates can be compared to the debates of other later well-known historical figures discussed in this website, such as those between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois, or Susan B. Anthony and those fighting for women’s suffrage in the 19th and 20th centuries. It is important to consider the implications of this because it may be useful in coalition-building today. As was evident with Lincoln and Douglass, approaches to a goal may be in tension with one another, but they can also serve to push each other. For this reason, perhaps we should welcome diverse approaches and competing strategies instead of viewing them as threatening.

Painting of the first Emancipation Proclamation reading in front of Lincoln’s Cabinet (painted by F.B. Carpenter) (Library of Congress)

[1] James Oakes, The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007), 165.

[2] Oakes, 109.

[3] Andrew DelBanco, The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War (Penguin Books, 2018), 70.

[4] Oakes, 109.

[5] Oakes, 109-121.

[6] DelBanco, 70.

[7] Frederick Douglass, “Fifth of July” Speech (1852) excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[8]Frederick Douglass, “Fifth of July” Speech (1852) excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[9]Frederick Douglass, “Fifth of July” Speech (1852) excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[10] Matthew Pinsker, “Man of Consequence: Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s,” The Dickinson Survey of American History, House Divided Project, 2009, (Accessed June 30, 2021), https://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-american/essay-man-of-consequence/#.

[11] Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided” Speech (1858), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[12]Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided” Speech (1858), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[13] Oakes,140.

[14] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address” (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[15] Oakes, 140.

[16] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address” (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[17] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address” (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[18] Oakes, 141.

[19] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address” (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[20] Oakes, 141.

[21] Abraham Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address” (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar; Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided” Speech (1858), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[22] Oakes, 142.

[23] Oakes, 142.

[24] Frederick Douglass, “Cast Off The Mill-Stone.” Douglass’ Monthly (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.

[25] Frederick Douglass, “Cast Off The Mill-Stone.” Douglass’ Monthly (1861), excerpted in Knowledge for Freedom Seminar.