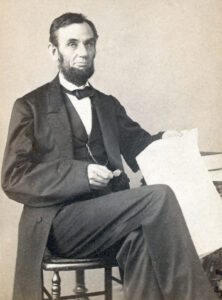

Lincoln on Freedom and Preservation of the Union

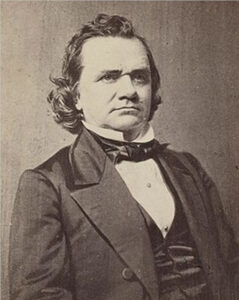

In 1858, Abraham Lincoln gave his “House Divided” speech when he accepted the Republican nomination to run for Senator in Illinois. However, this was more complex as Lincoln, a relatively unknown politician at the time, ran against Stephen Douglas, a powerful Democrat from the north, who in the midst of a bitter debate with President James Buchanan, drifted from the Democratic party and was encouraged by prominent national Republicans to switch and run for the Republican nomination. But in 1858, Illinois Republicans “broke new political ground by nominating Lincoln in advance of the legislative elections as their ‘first and only choice’ for U.S. senate.”[1]

In his speech, Lincoln sought to unite the Republican people around the anti-slavery cause, whose shared goal was the extinction of slavery. Using his now well-known quote “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” he argued that the nation would not be able to maintain itself until it converged on the slavery issue, and made the decision to be entirely pro-slavery or anti-slavery.

Lincoln clearly preferred the country to go the anti-slavery route and he explained that those who stood in the way of that were northern Democrats, like Stephen Douglas. In his speech, he discussed how there were some Americans who believed that Douglas may be on their side- the anti-slavery side. Additionally, they argued that Douglas may have been the only person capable of sparking change. Lincoln, however, was not of this mindset and emphasized that not only did Douglas not care whether slavery was abolished, he also encouraged the public not to care. Lincoln suggested that this was problematic as the slavery issue was too important and therefore the anti-slavery cause must lie in the hands of those “who do care for the result.” His goal was to unite the party against slavery, and against those who did not care about the fate of slavery.

This speech was seen as radical at the time, particularly as it related to his position on slavery, but Lincoln’s main priority was the preservation of the Union. He claimed that he foresaw an end to slavery, an institution that had been in place since the birth of the nation. Nobody had lived in a society in which slavery did not exist, so for many, the question shifted from one of freedom to one of equality. Americans did not know what would happen once slavery was abolished and slaves became free citizens. Northern Democrats feared a society in which white and black people were equal, and they interpreted Lincoln’s speech as a potential threat. But, nowhere in his speech did Lincoln address the topic of equality, or even the rights of black people. If he was already making a radical argument, why not go one step further and advocate for racial equality? Was it because he only cared about preserving the Union and not about the lives of black Americans? To me, freedom and equality go hand in hand, but I wonder if in Lincoln’s mind, he truly was able to separate them; abolition as one fight and racial equality as another. Or, as a calculated politician, was he censoring himself on a debate that remained too far in the future? In either case, Lincoln opted to abandon certain values in order to make incremental change. Although one can never know for sure if this was the right decision, it’s possible that if he had tried to do both, abolition might not have been achieved at all. However, the inevitable consequence of not focusing on equality may have been the perpetuation of racism and a greater struggle for citizenship for former slaves and black Americans.

Excerpt from Abraham Lincoln’s “House Divided” Speech, read by Charlotte Goodman with music by Nick Rickert:

By: Charlotte Goodman, June 2021

[1] Matthew Pinsker, “Man of Consequence: Abraham Lincoln in the 1850s,” The Dickinson Survey of American History, House Divided Project, 2009, (Accessed June 30, 2021), https://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-american/essay-man-of-consequence/#.