This post is the first of three posts on the Camp Nelson Stampede: see also Enslaved Women (Part 2) and Freedom and Community (Part 3)

DATELINE: JUNE 4, 1864, CAMP NELSON, KY

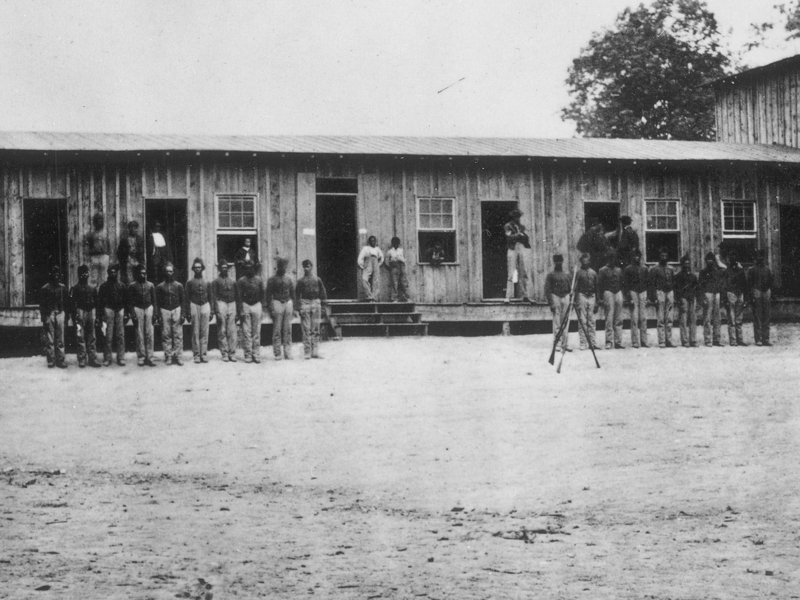

Black US soldiers at Camp Nelson (Explore KY History)

“Within a few days the negroes of Kentucky have become impressed with the idea that the road to freedom lies through military service, and there has been a stampede from the farms to the recruiting offices.” [1] So reported the Cincinnati Commercial on June 4, 1864. The federal government had finally opened enlistment–and thus a pathway to freedom–to enslaved men in the Bluegrass State. However, there was a catch: enslaved men first needed to secure their slaveholders’ consent to enlist. Throughout the spring and early summer of 1864, enslaved Kentuckians refused to take no for an answer; they were determined to enlist and gain their freedom, with or without their slaveholders’ approval. In just a matter of weeks, the initial stampede of enslaved men to recruiting offices and Camp Nelson pressured the US army into opening its ranks to all enslaved Kentuckians.

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

Unlike many pre-war group escapes in Kentucky, the “stampede” to Camp Nelson was not a single group of freedom seekers with one shared starting point; rather it consisted of a succession of group escapes originating from throughout the counties surrounding Camp Nelson. Collectively, those group escapes amounted to one of the largest wartime “stampedes”—thousands of enslaved men, women, and children escaped to Camp Nelson starting in the summer of 1864 and continuing through the summer of 1865.

Right from the beginning, newspapers employed the term “stampede” to describe freedom seekers’ rush to Camp Nelson. The Cincinnati Commercial described “a stampede from the farms to the recruiting offices.” Papers in Cleveland and San Francisco reprinted the Commercial’s original story under new headlines that described the “Exodus of Negroes from Kentucky.” [2]

Newspapers continued to use the term “stampede” to describe occasional upticks in the number of freedom seekers heading to Camp Nelson. In April 1865, a correspondent from Danville, Kentucky commented that “the stampede of negroes from this region to Camp Nelson has received a new impulse within a few days” due to rumors that the camp might close its doors. [3] Several months later in June 1865, a correspondent for the Cincinnati Commercial described another “stampede” after enslaved Kentuckians eavesdropped on a local politician’s speech insisting that Kentucky could maintain slavery for another seven years. “There happened to be quite a number of darkies listening to him, and the idea of seven years more of slavery was so distasteful to them that they concluded immediately to take the short cut to freedom via the army,” the journalist wryly reported. “Accordingly, they not only went themselves, but got all their neighbors to join them in a stampede for the nearest recruiting station.” [4]

MAIN NARRATIVE

The US army originally established Camp Nelson in 1863 as a supply depot, not as a center for African American recruitment. The camp was located in Kentucky, a loyal slave state which continued to fiercely resist federal antislavery policies. In hopes of appealing to white Kentuckians, President Abraham Lincoln had exempted the Bluegrass State from his Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. The Lincoln administration also held off enlisting enslaved Kentuckians into the US army, even though by mid-1863 the federal government had already begun recruiting enslaved men as soldiers in other border slave states such as Maryland and Missouri. [5]

Finally in April 1864, the US army’s manpower needs led federal officials to authorize limited Black recruitment in Kentucky. US general Stephen Burbridge sought to soften the blow by making several key concessions to Kentucky slaveholders. First, the federal government would compensate slaveholders $300 for each enslaved recruit. Secondly, prospective recruits needed to secure their slaveholder’s permission before they could enlist. Third, the US army would not send recruiters out onto plantations to enlist enslaved men, but would require enslaved recruits to journey to recruiting offices run by provost marshals (the army’s military police) where they could enlist. [6]

Enslaved men were determined to enlist, with or without their slaveholder’s blessing. As US officials quickly recognized, it proved almost impossible to determine on the spot whether slaveholders had actually given consent. At least some provosts went ahead and enlisted enslaved men without their slaveholders’ approval. In May 1864, a group of 15 enslaved men presented themselves for enlistment at the provost marshal’s office in Stanford, Kentucky. Even though only five of the recruits had their slaveholders’ consent to enlist, the local provost marshal forwarded all 15 men to Camp Nelson. [7] More often, US officials demanded hard proof of slaveholders’ consent. The provost marshal at Berea, Kentucky only agreed to enlist enslaved men who came to his recruiting office accompanied by their slaveholder. If he “let the slave[s] come and enlist at their own option,” the provost marshal explained, “all [the] slave men in the county would come.” [8]

Turning away prospective recruits left enslaved men vulnerable to violent reprisals by slaveholders and white Kentuckians, who were determined to stop Black enlistment at all costs. On May 10, a group of 17 enslaved men traveled from Green County more than 20 miles to Lebanon, where provost marshal James Fidler “kindly received” them, but explained that he would need written proof that their slaveholders had consented to them enlisting. Fidler supplied each man with “notes to their owners asking that the negroes be permitted to enlist.” Fidler’s attempt to follow the fine print of federal policy ended in tragedy. White Kentuckians “followed these black men from town, seized them and whipped them most unmercifully with cow-hides.” Declaring that “negro enlistment should not take place in Lebanon,” local whites threatened the provost marshal “with a mob” should he attempt to enlist any Black recruits. [9]

Slaveholders also stepped up violence towards enslaved women, both in retaliation for their husbands enlisting and also to dissuade them from any designs they might have on joining their husbands at Camp Nelson. “My master beat me over the head with an axe handle,” enslaved Kentuckian Clarissa Burdett later testified, “saying as he did so that he beat me for letting [husband] Ely Burdett go off…. He bruised my head so that I could not lay it against a pillow without the greatest pain.” [10] Whenever opportunity presented itself, enslaved women gathered their children and slipped away to Camp Nelson, where they hoped to reunite their families.

Enslaved Kentuckians who withstood the violence and reached Camp Nelson met with a disappointing reception from the US army. When 250 enslaved men “thirsting for freedom” departed Danville, Kentucky on May 23 bound for Camp Nelson, students at Centre College “assailed them with stones and the contents of revolvers.” The men braved the assault and made it the sixteen miles to Camp Nelson later that same afternoon, only to be turned away by camp commandant Col. A.H. Clark, who claimed he “had no authority” to muster them into the army. [11]

Clark was even less sympathetic to the many enslaved women who had risked it all to accompany their husbands to Camp Nelson. Clark ordered his subordinates to exclude enslaved women from camp and threaten that “if they return, the lash awaits them.” [12] Despite US officials’ best efforts to keep them out, enslaved women kept coming back, determined never return to slavery and intent on keeping their families together. “There is not one among two hundred that want to go,” conceded one US army official, who acknowledged that enslaved women believe “that they will be killed by their masters if they return.” [13]

AFTERMATH

By June 1864, rampant violence against enslaved recruits prompted federal officials to open up enlistment to all enslaved men in Kentucky. “It became absolutely necessary for the protection of the slave to enlist him without the consent of the owner,” explained provost marshal James Fidler in Lebanon, Kentucky. [14] Federal officials back in Washington agreed. “In view of the cruelties practiced in the State of Kentucky by owners of slaves towards recruits,” assistant adjutant general C.W. Foster suggested that the US army should “accept and enlist any slave who may present himself for enlistment,” regardless of whether their slaveholder approved. In mid-June, US officials in Kentucky announced that the army would now accept the services of any enslaved men willing to enlist, regardless of whether their slaveholder approved. [15]

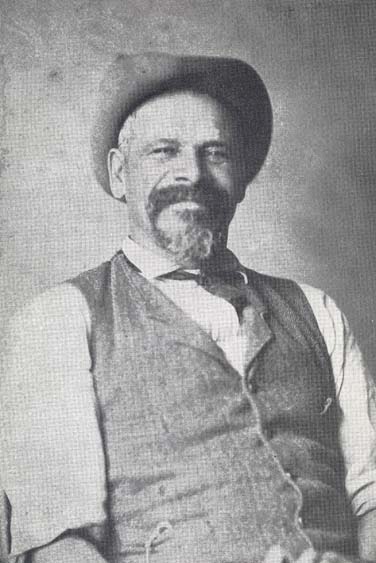

Freedom seeker Peter Bruner (Bruner, A Slave’s Adventures Toward Freedom, 1918)

Following the change in federal policy, growing numbers of enslaved Kentuckians streamed into Camp Nelson. In early July 1864, Peter Bruner escaped from Richmond, Kentucky and “came upon sixteen colored fellows who were on their way to Camp Nelson and of course I did not get lonesome.” Bruner and his fellow freedom seekers took advantage of the new federal policy allowing them to enlist without their enslavers’ consent. “When I had run off before and wanted to go in the army and fight they said that they did not want any darkies, that this was a white man’s war,” Bruner recalled. However, when Bruner and the 16 other escapees arrived at Camp Nelson, military officials mustered Bruner into the newly formed 12th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. [16]

Camp Nelson quickly became an oasis for Black freedom in slaveholding Kentucky. “See how much better off we are now dan we was four years ago,” one unidentified freedom seeker-turned-soldier declared the following summer in the presence of a London abolitionist. “It used to be five hundred miles to git to Canada from Lexington, but now it’s only eighteen miles! Camp Nelson is now our Canada.” [17]

The reworked federal policy helped transform the camp into a major site of military emancipation, but still did not clarify the status of enslaved women and children who crowded into Camp Nelson alongside their husbands and fathers. Despite the US army’s best efforts to keep them out, enslaved women would continue to head to Camp Nelson in an effort to keep their families together. (Continue reading part 2)

FURTHER READING

A robust body of scholarship has highlighted Camp Nelson’s importance as a redoubt for Black emancipation in slaveholding Kentucky. A good starting place is Richard Sears’s Camp Nelson, Kentucky (2002), an edited collection of primary sources covering the camp’s existence. The Freedmen and Southern Society Project’s Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation series 2 (The Black Military Experience), also features primary sources related to Black recruitment and Black family life at Camp Nelson. [18]

Historians have also explored the experiences of freedom seekers heading to Camp Nelson, as well as the site’s continuing significance to public memory of the Civil War. Amy Taylor’s Embattled Freedom (2018) foregrounds the experiences of freedom seeker Gabriel Burdett, his “sister-in-law” Clarissa, and their extended family as they sought liberation at Camp Nelson. [19] W. Stephen McBride argues in “Camp Nelson and Kentucky’s Civil War Memory” (2013) that the Camp Nelson National Monument remains an important site in shaping public memory of the Civil War. By highlighting the crucial contributions Black men and women made to US victory, Camp Nelson gives lie to Lost Cause narratives which downplay the centrality of emancipation. [20]

[2] “Kentucky Negro Exodus,” Cleveland (OH) Daily Herald, June 6, 1864, p. 4; “Exodus of Negroes From Kentucky,” San Francisco (CA) Daily Evening Bulletin, June 29, 1864, p. 3; A July 1865 referred back to the “stampede of slaves from surrounding country” who “came here in May and June of ’64 by scores.” See “Refugee Home in Kentucky,” Worcester (MA) Spy, July 21, 1865, p. 2.

[3] “Stampede of Negroes,” Louisville (KY) Daily Journal, April 28, 1865, p. 1.

[4] Cincinnati Commercial quoted in, “How Dinah Got a Companion for Life,” New Orleans (LA) Times, June 19, 1865, p. 3.

[5] Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), ser. 2 (The Black Military Experience), vol. 1, 193; Amy Murrell Taylor, Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 186-187.

[6] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 193; Amy Murrell Taylor, Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 186-187.

[8] John G. Fee to Brother Jocelyn, May 11, 1864, Berea, Ky., in Richard D. Sears, Camp Nelson, Kentucky: A Civil War History (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2002), 56-57.

[9] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 257.

[10] Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 188.

[11] Report of Thomas Butler, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 58.

[12] “Slave-Hunting in Kentucky,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 18, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 63-65.

[13] Hanaford to McQueen, May 26, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 60; Hanaford to Dickson, July 6, 1864, in Sears, Camp Nelson, 94.

[14] Freedom, ser. 2, vol. 1, 257.

[15] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), ser. 3, vol. 4, 422, [WEB]; Lorenzo Thomas, Special Order No. 20, June 13, 1864, cited in Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 187.

[16] Peter Bruner, A Slave’s Adventures Toward Freedom: Not Fiction, but the True Story of a Struggle (Oxford, OH: n.p., 1918), 42-43 [WEB]

[17] [Joseph Simpson], Letters from Joseph Simpson, Manchester (London: Friends’ Central Committee for the Relief of the Emancipated Negroes, 1865), 23.

[18] Sears, Camp Nelson; Freedom ser. 2 (The Black Military Experience).

[19] Taylor, Embattled Freedom, 174-208, 221-230.

[20] W. Stephen McBride, “Camp Nelson and Kentucky’s Civil War Memory,” Historical Archaeology 47, no. 3 (2013): 69–80.