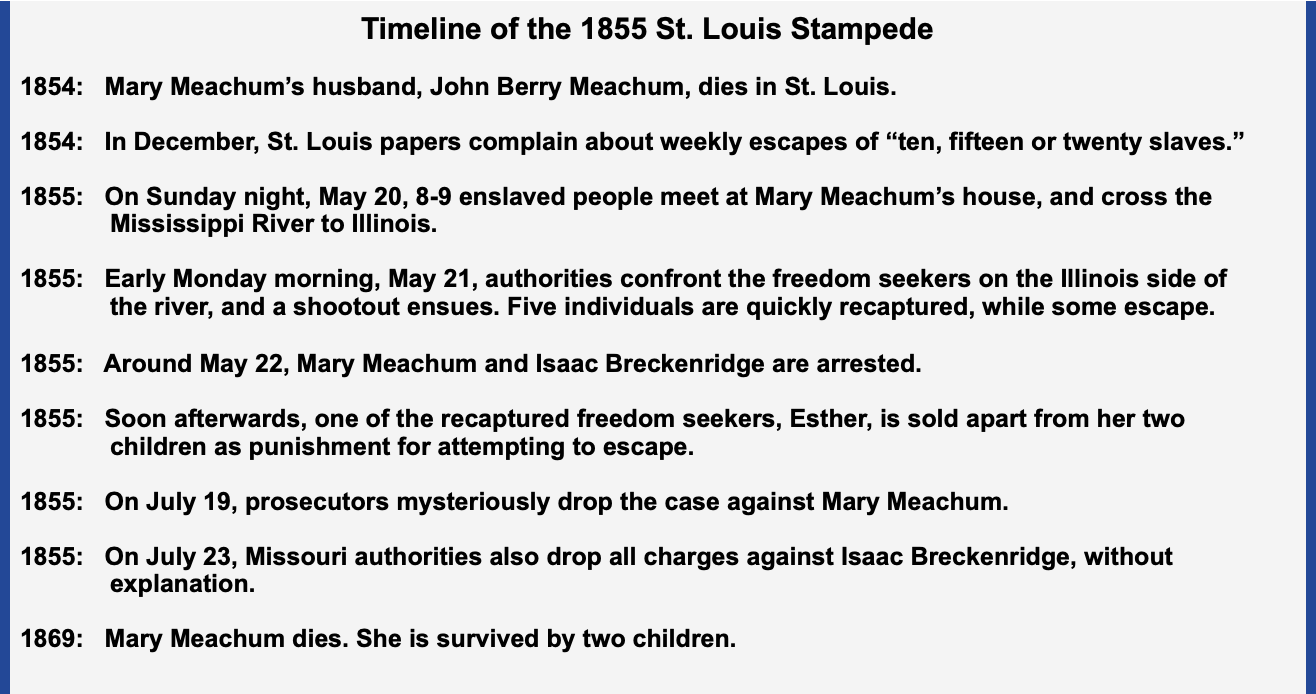

DATELINE: ST. LOUIS, NIGHT OF MAY 20-21, 1855

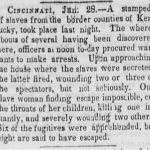

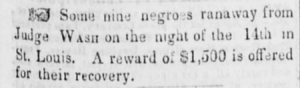

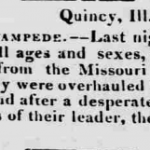

On Sunday night, May 20, 1855, a group of about eight or nine freedom seekers set out across the Mississippi River near St. Louis on a skiff designed to take them over to the free state of Illinois. Hours earlier, they had met under the cover of darkness at the home of Mary Meachum, a leader in St. Louis’ black community and one of the likely masterminds behind the escape. According to some newspaper reports, two other local black organizers of the nighttime expedition were Isaac Breckenridge and Julia Burrows. Some accounts also identify unnamed white antislavery activists and a black guide from Illinois named “Freeman” meeting the freedom seeking group on the other side of the river. Regardless, word had gotten out about the escape and armed police agents along with slave catchers were waiting for the freedom seekers on the Illinois shore. In the predawn hours of Monday morning, May 21, the confrontation quickly turned into a firefight, and at least five of the freedom seekers were taken back to St. Louis in chains. Within a few days, authorities had also arrested Breckenridge, Burrows and Meachum.[1]

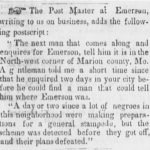

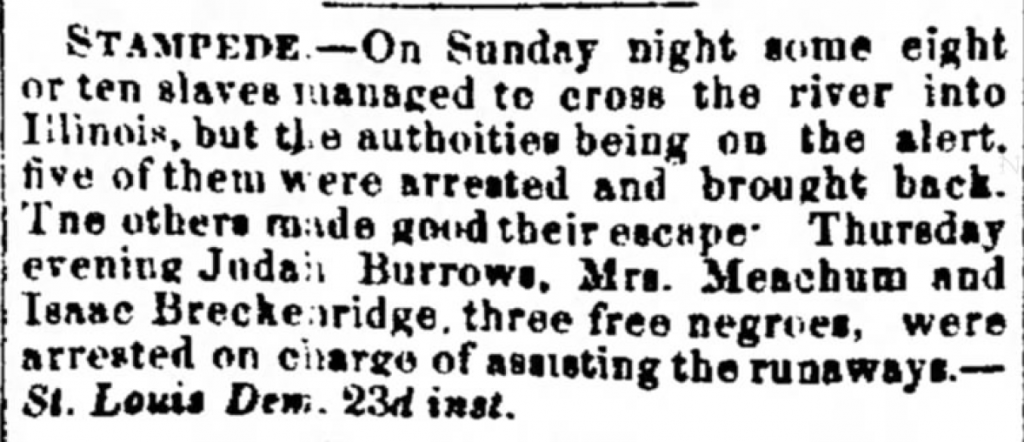

St. Louis Democrat reprinted in Milwaukee (WI) Daily Free Democrat, May 26, 1855

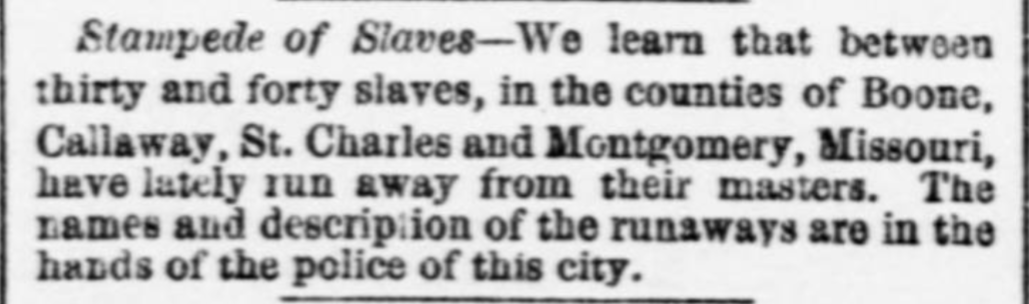

STAMPEDE CONTEXT

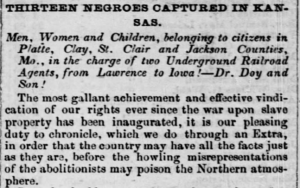

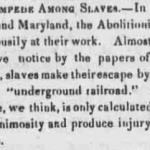

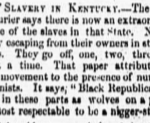

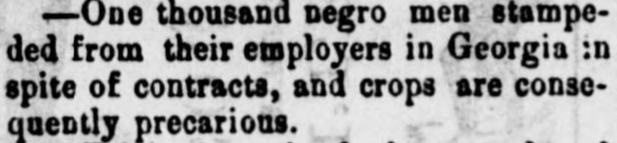

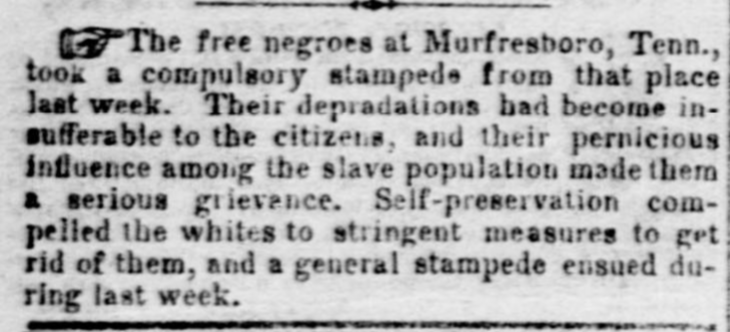

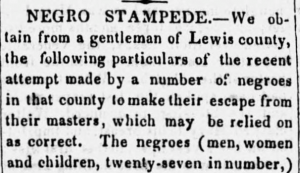

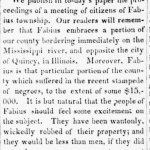

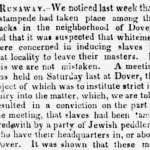

News of the dramatic flight and altercation was reported in the St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican the next day. “SLAVES CAPTURED,” crowed the pro-slavery newspaper, ending a lament that not all of the “scoundrels” were captured. At least two other newspapers, the Thibodeaux Minerva in Louisiana and the Chicago Tribune reprinted the same article in the following weeks.[2] The event was first referred to as a stampede on May 26, when the Milwaukee (WI) Daily Free Democrat wrote a short story about the escape and titled it “Stampede,” and then again on May 31 when the Glasgow (MO) Weekly Times published its own article entitled “Slave Stampede.”[3] The local section of the Daily Missouri Republican sporadically reported on the criminal proceedings for the three Underground Railroad operatives over the following months, but the story appears to have disappeared from coverage elsewhere.

MAIN NARRATIVE

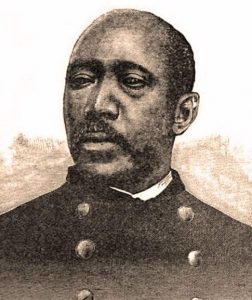

The arrest of Mary Meachum, one of the agents who was presumably behind the stampede, was big news within her community. After 40 years in St. Louis, Mary held a number of prominent roles. She and her late husband, John Berry Meachum, were both formerly enslaved, and they dedicated their lives to helping the free and enslaved black people of St. Louis. Mary and John had founded one of the first black churches in the city, the African Church of St. Louis, as well as a school in for free and enslaved blacks, where they taught religious and secular studies, as well as trades like carpentry. They also “purchased” their own slaves, presumably so that they could work legally toward their own freedom. In secret, the Meachums had also served as agents of the Underground Railroad, planning and orchestrating escapes for their own students and members of the congregation. Historian Richard Blackett notes that runaway slave advertisements in St. Louis during the 1850s “frequently mentioned that slaves disappeared on Sunday evenings following the end of church services.”[4] When John Meachum died in 1854, Mary continued both their legal and illegal work on her own, until she was caught in May 1855.

The arrest of Mary Meachum, one of the agents who was presumably behind the stampede, was big news within her community. After 40 years in St. Louis, Mary held a number of prominent roles. She and her late husband, John Berry Meachum, were both formerly enslaved, and they dedicated their lives to helping the free and enslaved black people of St. Louis. Mary and John had founded one of the first black churches in the city, the African Church of St. Louis, as well as a school in for free and enslaved blacks, where they taught religious and secular studies, as well as trades like carpentry. They also “purchased” their own slaves, presumably so that they could work legally toward their own freedom. In secret, the Meachums had also served as agents of the Underground Railroad, planning and orchestrating escapes for their own students and members of the congregation. Historian Richard Blackett notes that runaway slave advertisements in St. Louis during the 1850s “frequently mentioned that slaves disappeared on Sunday evenings following the end of church services.”[4] When John Meachum died in 1854, Mary continued both their legal and illegal work on her own, until she was caught in May 1855.

- John Berry Meachum Courtesy of Wikipedia.org

Not much is known about the two other free blacks who helped Meachum. An 1860 census reveals that one of them, Isaac Breckenridge, moved to St. Louis from North Carolina with a woman, likely his wife, named Fanny. Whether or not the Breckenridges were born free or enslaved is unknown, but by 1855, they were free and working in the city as whitewashers.[5]

Even though it ultimately failed, the group escape of May 21 must have been carefully planned. Meachum, Burrows, and Breckenridge were the only agents arrested the night of the escape, but the May 22 Daily Missouri Republican article repeatedly claimed that other “white cowardly agents” had managed to escape the slave-catching posse by fleeing into the woods. Of course, it was also possible that Meachum, Burrows, and Breckenridge were the only ones behind the escape, but that the pro-slavery journalists were simply unable to believe that a few people of color could hatch such an ambitious escape scheme.

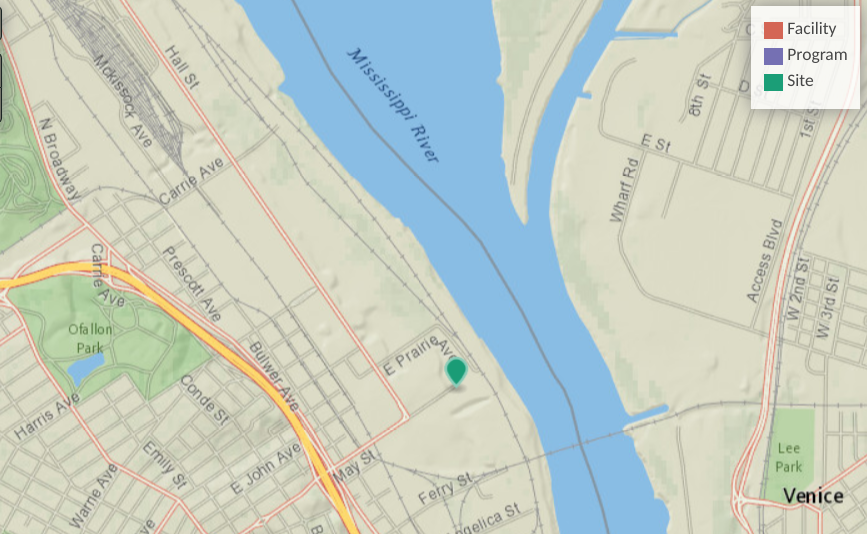

Whatever the number of people involved, the entire group met at Mary Meachum’s home somewhere on 4th street, and then fled to a skiff located “a short distance above Bissell’s Ferry” that they used to cross the Mississippi. Across the river, a wagon was already waiting to take the escapees further north to Alton and then to Chicago, where they would be safer from slave catchers.

Location of escape party’s departure on the night of May 21, 1855. Today, it is the site of the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing. Map courtesy of the National Parks Service.

Two of the enslaved men, 22-year-old Ben and another unidentified individual, split from the escape party before crossing the river. Ben had fled from slaveholder H.H. Cohen’s residence along the Clayton Road, a short distance outside of the city, while the other freedom seeker was claimed by Sheriff Turner Maddox. Their decision likely spared them from a cruel fate. As the six remaining escapees reached the Illinois shore, they came face to face with two slaveholders and a police officer. Two shots were fired, and one freedom seeker, possibly 20-year-old Jim Kennerly, immediately dashed into the woods and avoided capture. The other five, two men, and a woman named Esther with her two children, were captured and returned to St. Louis in chains. [6]

After being held in the St. Louis jail for weeks, Meachum, Burrows, and Breckenridge each individually faced a trial by jury for “enticing away slaves,” although many of the details of their cases, including the entirety of Burrows’, are lost. The Daily Missouri Republican reported that an “Isaac (colored)” pled not guilty during his arraignment” on May 25 and began his trial on July 20, and arrest records reveal that his case was dropped at the decision of the state prosecutor, although his reasoning remains a mystery.[7] Census records indicate that Breckenridge and his wife were living free in St. Louis in 1860.[8]

Mary Meachum’s case is equally as mysterious. On July 16 her attorney filed a motion to quash her indictment, and on July 19 Mary’s charges were also dropped and she was set free to continue her life as a free woman in St. Louis.[9] She continued to lead and serve her local community, appearing in papers again in 1864 as the president of the Colored Ladies Soldiers’ Aid Society, which provided resources and care black soldiers and enslaved people who had escaped during the war. [10] Mary died in 1869, leaving behind two children, William and John.[11]

AFTERMATH AND LEGACY

As for the five enslaved men, women, and children who were caught during the night of the escape, they were returned to their slaveholders in St. Louis and punished for their insubordination. Esther, the mother who tried to flee with her children, was separated from her family and sold downriver for her

Henry Shaw, slaveholder of Esther and her children and prominent St. Louis businessman. Courtesy of Wikipedia.org

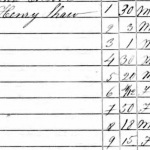

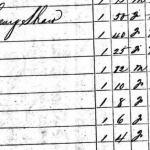

punishment by her slaveholder Henry Shaw, a prominent St. Louis businessman.[12] Shaw was born in England and migrated to Missouri in 1819. Amassing significant wealth as a business owner selling tools and cutlery in the growing town, Shaw became one of the largest landowners of St. Louis. He developed a number of parks, acquiring a lasting reputation as a philanthropist. In 1993, a star was dedicated on the St. Louis Walk of Fame for Henry Shaw’s foundation of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Shaw had owned several slaves at a time since 1828.[13] Esther likely worked as a servant in his household. When she took her two sons with her on the disastrous escape mission in 1855, they were around six and eight years old. Most accounts report that Shaw stopped owning slaves after 1856, but slave census records indicate he still owned eight slaves in 1860, including a twelve year old boy who may have been Esther’s elder son.[14]

However, another person enslaved by Shaw apparently managed to elude captors. That man, 20-year-old Jim Kennerly, may well have been the sixth person aboard the boat alongside Esther and her children, who sprinted to freedom when the firefight erupted. Regardless of whether that individual was Kennerly, what is clear is that days later, Shaw was still searching for his runaway bondman. On May 25, the slaveholder filed a notice with the editorial office of the Missouri Republican, offering a $300 reward for Kennerly’s recapture. There are no records to indicate the freedom seeker was ever brought back to St. Louis. Likewise, 22-year-old Ben and the unidentified enslaved man claimed by Sheriff Maddox also apparently evaded recapture, and by all indications made their way to freedom. [15]

The Meachum escape has been well commemorated in St. Louis. One hundred and fifty years later, the spot where the escape group left Missouri’s shore became an historic site on the Mississippi River Waterfront Trail and a stop on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. Named the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing, the site houses both public art and a community building. Every spring since 2005, the Annual Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing Celebration commemorates the freedom attained by some, and the suffering faced by others as a result of this failed escape. The annual commemoration includes music, games, history lessons, competitions and a reenactment the events of the night May 21.[16]

Mural at the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing site. Courtesy of Google Maps.

FURTHER READING

Some historians disagree over how to characterize John Meachum’s role in the antislavery movement. Lea VanderVelde suggests in Redemption Songs: Suing for Freedom before Dred Scott (2014) that freedom suits filed against Meachum undertaken by an enslaved woman named Judy Logan indicate that he may not have always been so eager to “free” the enslaved people whom he had purchased. The woman’s complaints against Meachum and his refusal to grant her freedom, juxtaposed with the dozens of other enslaved folk that Meachum purchased and ultimately freed, raise questions about what the man was really like. For further reading about John Meachum, see also R.J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (2018).

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

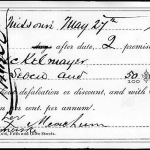

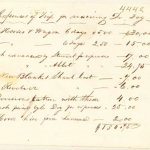

- Check signed by Mary Meachum, May 27, 1869. (Ancestry)

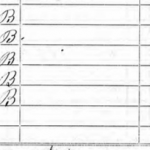

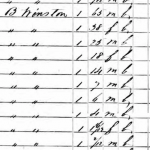

- Henry Shaw owned 9 slaves in 1850. (U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ancestry)

- Shaw owned 8 slaves as of 1860. (U.S. Census, Slave Schedules, Ancestry)

- Isaac Breckenridge is listed as a whitewasher in St. Louis, 1865. (St. Louis, MO Directory, Ancestry)

ENDNOTES

[1] “Slaves Captured,” St. Louis Daily Missouri Republican, May 22, 1855, p. 3: 2. The St. Louis Democrat was the only newspaper source that actually identified Isaac Breckinridge and Jordan (or perhaps Judah) Burrows (or perhaps Burroughs) as being arrested along with Mary Meachum in a report from May 23 that was reprinted in “Stampede,” Milwaukee (WI) Daily Free Democrat, May 26, 1855, [WEB]. The information about “Freeman” appeared in the St. Louis Weekly Pilot, which mistakenly claimed that he had been fatally wounded during the firefight; see “Killed,” St. Louis Weekly Pilot, May 26, 1855 and the correction to the rumor (actually from the day before) in “Humbug,” St. Louis Missouri Daily Republican, May 25, 1855. Special thanks to former Missouri Department of Natural Resources historian and researcher Kris Zapalac whose unpublished paper, “Mary Meacham Crossing Site,” for the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom helped to bring the confusing coverage and still unanswered questions about “Freeman” to our attention.

[2] “Slaves Captured,” Thibodeaux Minerva (Thibodeaux, LA), June 2, 1855; “Slaves Captured,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), May 25, 1855.

[3] “Stampede,” Daily Free Democrat (Milwaukee, WI), May 26, 1855, [WEB]; “Slave Stampede,” Glasgow Weekly Times (Glasgow, MO), May 31, 1855, [WEB].

[4] R.J.M. Blackett, The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 143.

[5] 1860 US Federal Census, St Louis Ward 3, St Louis (Independent City), Missouri; Roll M653_655, p163.

[6] “Slaves Captured,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 22, 1855; “One Hundred Dollars Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 24, 1855; “$300 Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 27, 1855. Morrison’s St. Louis Directory (St. Louis: Missouri Republican Office, 1852), 51, [WEB]; Kennedy’s Saint Louis City Directory (St. Louis: R.V. Kennedy, 1857), 48, 139, [WEB]; The identification of Ben comes from a $100 reward posted by slaveholder H.H. Cohen in the Missouri Republican on May 24 (noting that Ben had escaped on “Sunday evening last,” May 20), and the paper’s own reporting that “a negro belonging to Mr. Cohen” had joined the party but did not cross the river with the remainder of the group. See “One Hundred Dollars Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 24, 1855. Of the six runaways who remained in the boat, at least three were claimed by slaveholder Henry Shaw (Esther and her two children), one held by stable keeper John F. Thornton, and another held by a slaveholder named McElroy from St. Louis county. The sixth person, described only as “another negro man, who crossed at the same time” may well have been Jim Kennerly. Soon after the stampede, slaveholder Henry Shaw advertised a $300 reward for Kennerly’s recapture, noting that he had escaped from Shaw’s “country residence” near St. Louis on Sunday, May 20. See “$300 Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 27, 1855. For the identification of Thornton as the slaveholder, see Morrison’s St. Louis Directory, 255, 257, [WEB].

[7] “Criminal Court,” Daily Missouri Republican, May 25, 1855; “Criminal Court,” Daily Missouri Republican, July 20, 1855. Isaac Breckinridge, cases 135 and 135, St. Louis Criminal Court Record Book 8 (May 24, 1855), Missouri State Archives –St. Louis, MO. Special thanks to Michael Everman.

[8] 1860 US Federal Census, p163.

[9] “Criminal Court,” Daily Missouri Republican, July 19, 1855. Mary Meachum, cases 137 and 138, St. Louis Criminal Court Record Book 8 (May 25, 1855; July 16, 1855; July 19, 1855), Missouri State Archives –St. Louis, MO. Special thanks to Michael Everman.

[10] Romeo, Sharon E., “Freedwomen in Pursuit of Liberty: St. Louis and Missouri in the Age of Emancipation,” PhD thesis, University of Iowa (2009), 45.

[11] “Mary Meachum,” Find A Grave [WEB]

[12] Andrew Hurley, “Narrating the Urban Waterfront: The Role of Public History in Community Revitalization,” The Public Historian 2, no 28 (2006): 34.

[13] Joseph Schuster, “Our Mission and History,” Missouri Botanical Garden, [WEB]. “Henry Shaw,” St. Louis Walk of Fame, [WEB]

[14] 1860 US Census Slave Schedule, St. Louis County, page 3.

[15] “One Hundred Dollars Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 24, 1855; “$300 Reward,” St. Louis Missouri Republican, May 27, 1855.

[16] Hurley, 33.